By Laurie D. Morrissey

If you are out walking on an early winter morning, you might be lucky enough to see some of nature’s most beautiful and ephemeral sights: hair ice and frost flowers, both snow-white and delicate against the dull forest floor.

Recently, a friend sent me a photo of hair ice, seemingly sprouting from a rotten log in the woods. She guessed she was seeing tufts of deer or rabbit fur curled around a branch – until she touched one and it melted. Hair ice forms on dead wood, aided by the presence of the Exidiopsis effusa fungus. Scientists believe that as the fungus breaks down the wood of a broad-leafed tree species, it produces complex molecules that mix with the water in the stem. Moisture near the surface of the dead branch or log is extruded from the pores of the wood and freezes into thin hairs of ice, which build up overnight into what looks like a tuft of wool or a white, shiny beard.

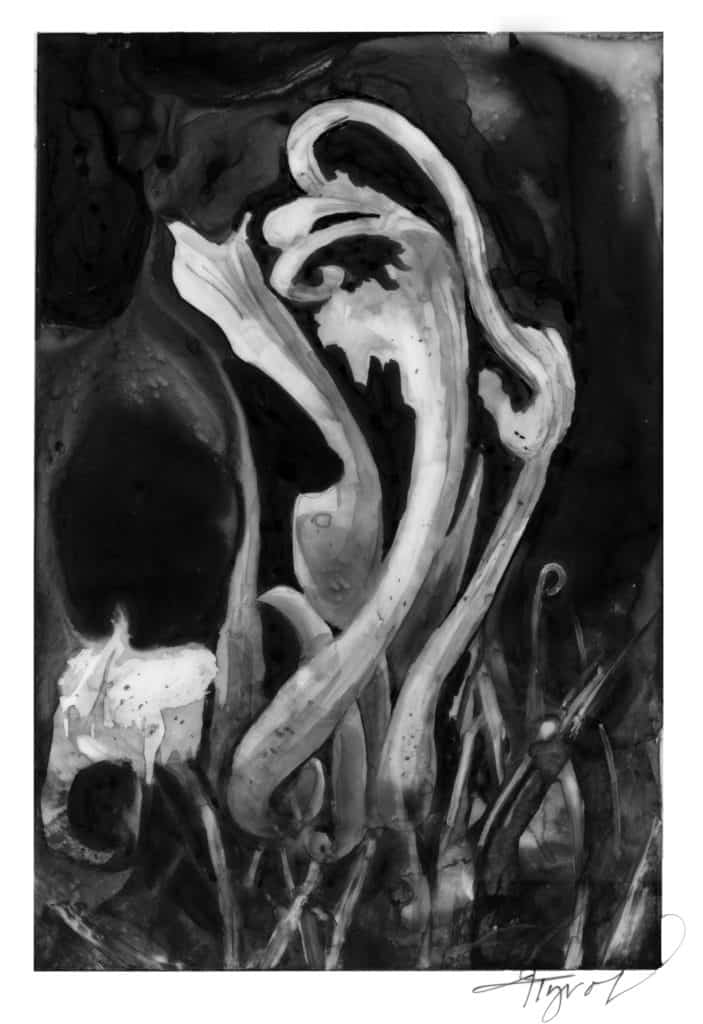

Frost flowers are similar, but occur on the stems of certain plants. They may resemble white ribbon candy, flowing curtains, swanlike sculptures, serpentine swirls, silky spirals, or glossy fans. Despite the name, they’re neither flowers, nor frost. While true frost occurs when moisture in the air condenses on a cold surface, these fanciful shapes result when sap, augmented by water drawn up from the roots, slowly pushes through the stem of an herbaceous plant and freezes on contact with the cold. They form most often near the base of the stem, but may extend further up.

Frost flowers occur so infrequently that many woods walkers never see them. Their rarity is largely due to the limited circumstances that create them. The ground must be warm enough for the plant’s root system to be active and the air must be cold enough to freeze the water flowing up its conductive tissues. However, it’s not uncommon for them to form in the same area night after night, to the delight of those early morning perambulators lucky enough to spot them.

New Hampshire’s state botanist, William Nichols, knows of only a few northeastern United States plant species that form frost flowers: the native Canada frostweed, which occasionally occurs in central and southern New England in dry, open fields and woodlands; the non-native wingstem crownbeard, which has naturalized in Massachusetts; and the rare sweet-scented camphorweed. Of these, only Canada frostweed creeps into central and northern New England, he said. Frost flowers also have been observed on certain garden plants, such as vinca and salvia.

Frost flowers have appeared in the botanic literature since at least the early 19th century and, surprisingly, are not strictly northern phenomena; they occur as far south as Georgia. They are the subject of much scholarly research and even have a scientific name. The late Robert Harms of the University of Texas, Austin (a linguist, not a botanist), coined the term “crystallofolia” in the 1960s because he believed the forms resembled leaves (Latin folia).

James Carter, an Illinois State University geologist, became fascinated by frost flowers when he spotted them while hiking in Tennessee in 2003. He described four products of ice segregation in nature: ice flowers on plant stems, hair ice on dead wood, needle ice in soil, and pebble ice on small rocks on the ground surface. He refers to ice that extrudes from linear cracks on plant stems as ice flowers and ice ribbons rather than frost flowers, but notes that there is no widely accepted term. (I’ve come across such labels as ice fringes, frost freaks, and rabbit ice to describe frost flowers.)

Carter writes that he knows of about 40 species worldwide that support the growth of ice flowers. He is, perhaps, the world’s only ice flower farmer; the professor has planted white crownbeard and salvia in buckets and flower beds in his yard and photographed the formations that appeared.

Now that we’re well into winter, the opportunity to see frost flowers or hair ice is most likely past for the time being. I may have to wait until next November to spot these fleeting, frozen forms, but I plan to be on the lookout.

Laurie D. Morrissey is a writer who lives in Hopkinton, New Hampshire. Illustration by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.