British soldier lichens are among the first wild things I remember being able to identify as a child. I loved spotting this lichen during forays into the woods – on a giant boulder or atop a decaying stump – its tiny, bright red caps seemed whimsical and somehow happy. I still love to find British soldiers, and they offer a welcome pop of color, especially during these days when the landscape is muted.

Lichens are fascinating things, really, the result of an intricate relationship between a fungus and an alga (or a cyanobacterium). Lichens are named for their fungal partner, so British soldiers are scientifically called Cladonia cristatella. This fungus has a symbiotic relationship with the alga called Trebouxia erici.

Both the fungus and the alga of a lichen rely on the other for survival. The fungus garners food from the alga’s photosynthesizing. In return, the fungus, which typically sandwiches the alga in a lichen, provides structure, water retention, and protection from bright sunlight.

Neither fungus nor alga would survive well on its own, but together they create some marvelous lichens – like British soldiers. This particular lichen tends to grow in places with some protection from wind and weather and is typically found close to the ground: on stumps, around the base of a tree, in mossy areas, or in the crevices of boulders.

Some animals eat lichens, and hummingbirds and others sometimes use them in nest-building, said mycologist Thomas Roehl, who maintains a website dedicated to mushrooms and lichens (fungusfactfriday.com). Insects sometimes use lichens as camouflage and protection.

“I don’t know if any animals specifically eat C. cristatella, … or use the British soldier lichen” as camouflage, Roehl said “But I’m sure many animals use it when they find it.”

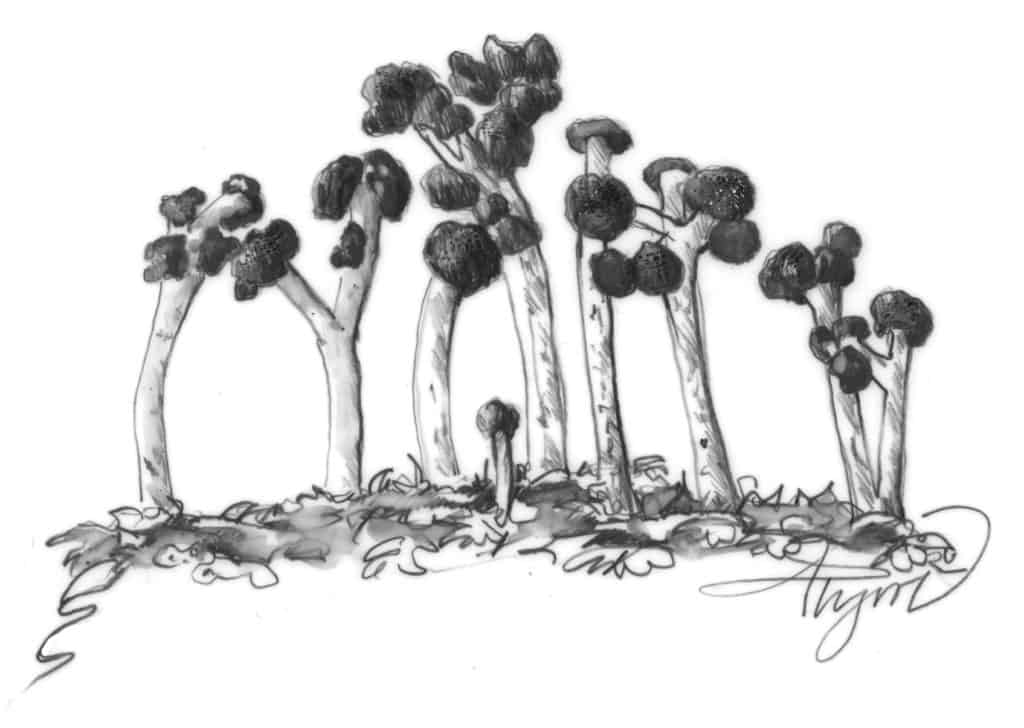

British soldiers are fruticose lichen, made up of cylindrical stems that extend into tiny branches, making the lichen seem like a miniature tree from a Dr. Seuss story. The branches are generally pale green and sometimes bumpy. Roehl says the green color comes from the algal partner and is brighter when the lichen contains more water and can actively photosynthesize.

Roehl explains that the branches of C. cristatella have three layers of cells: cortex, photobiont, and medulla. The cortex’s dense layer of fungal cells protects the inner layers. The photobiont layer contains the algal cells, each held in place by a net of fungal cells. This is where the algae and fungi exchange nutrients and sugars. The medulla comprises the center of the branch and supports the lichen structure.

The British soldier’s claim to fame, of course, is its bright red top, which some think is reminiscent of the red jackets worn by the British “Redcoats” during the Revolutionary War. This is the lichen’s fruiting body, its reproductive structure or “apothecia.”

Like other lichens, British soldiers can – in theory, anyway – reproduce both sexually and asexually, with the latter occurring when a piece of the lichen breaks off and reattaches to a substrate elsewhere.

The apothecia contain spores that can be released. These carry fungal DNA, but no algae, so a spore would have to land right next to an algal cell to reproduce this way.

“The chances of this happening are very slim,” Roehl writes on his website. “However, C. cristatella is almost always found with an apothecium atop every one of its branches. This indicates that the fungus is devoting a surprising amount of energy to sexual reproduction. If this process was useless, evolution would have gotten rid of it a long time ago.”

Whatever the reason for those scarlet-hued tips, and no matter how many times I spot British soldier lichens reaching upwards on tiny, crooked branches, the pop of color is always a surprise and a welcome bit of brightness.

Meghan McCarthy McPhaul is an author and freelance writer based in Franconia, New Hampshire. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine (northernwoodlands.org) and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation ([email protected]).