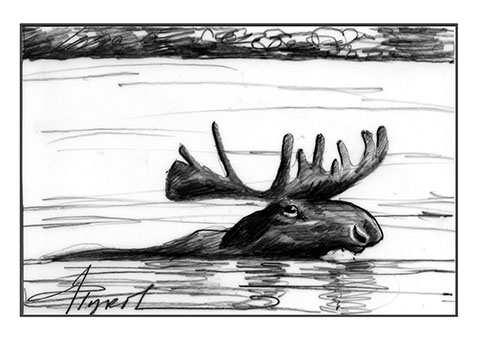

On an October day years ago, my husband and I were canoeing on a pond in the Green Mountain National Forest. We heard crashing in the bushes along the shoreline just before a magnificent bull moose with large antlers appeared. He plunged into the water and swam across the pond, only 50 feet from where we were floating quietly in our canoe. I still remember the silhouette of his massive head and the glistening beads of water on his neck. The bull must have been on the trail of a cow moose, as he seemed oblivious us. When he reached the opposite shore, he climbed out of the water and trotted off into the woods, grunting.

This moose was in “rut,” a term used to describe the breeding season in members of the deer — or cervid — family. The rut occurs between mid-September and mid-October, when cow moose come into estrus and bulls are laser-focused on breeding with them. Scientists believe daylength triggers a rise in hormones that stimulates reproductive behavior.

By late summer, a bull moose’s antlers are fully developed. As testosterone levels increase in September, the velvet skin covering of blood vessels and nerves — which aids in antler growth — dries and sheds, leaving hard antlers with sharp points attached to the broad palms. Moose rub their antlers against trees to scrape off the velvet. Antlers are designed to impress females, to intimidate rival males, and for fighting. A bull moose’s neck muscles also expand to twice their normal size for the rut, and thick forehead skin serves as armor against punctures.

During rutting season, bulls travel widely in search of cows, responding to their bellows and the calls of rival bulls. Scent-marking also plays an important role in attracting a mate; both sexes leave calling cards by rubbing their heads against trees. Bull moose dig pits in the ground with their front hooves and urinate into these depressions, which are typically 1½ to 3½ feet long, 1 to 3 feet wide, and 3 to 6 inches deep. Bulls wallow in their rut pits, anointing themselves with their musky odor. Cows are attracted to these pits and have been observed rolling in them and keeping other cows away from the wallows of a preferred male. Bulls travel among their rut pits, checking for cows along the way. If accepted by a cow, a bull usually stays with her for about a week, courting and mating. The couple may take turns mud-bathing, rubbing against each other, and following one another.

In a long-term study of moose behavior in Alaska’s Denali National Park, wildlife biologist Victor Van Ballenberghe found that large, dominant bulls performed 88% of all matings. They accomplished this by defending cows from smaller bulls, aggressively chasing other bulls away, and defeating challengers in fights. Van Ballenberghe observed battles between two mature bulls of about the same size that began with intense displays: the moose pawed the ground, thrashed their antlers against shrubs, and displayed their bodies and racks. Then they rammed their antlers together and shoved back and forth until one moose gave up and left the area. These violent clashes may last for hours and can seriously wound or even kill an opponent. If the bulls’ antlers become interlocked, both animals will die. Hikers and hunters may find torn-up shrubs, tufts of hair, and pieces of antlers after a moose fight.

After mating with one cow, the bull leaves to breed with successive cows. Van Ballenberghe found that most females mated with only one male. The rut ends when all cows in the area have passed through estrus. Afterwards, bulls are exhausted and spend long hours recuperating. They do not eat much during the rut and lose considerable weight, so must feed heavily in late fall to prepare for winter. Cows give birth to one or two calves in spring.

It is wise to give these huge, powerful animals a wide berth any time of year, but especially during the rut, when they’re more aggressive. Moose occasionally approach humans in the woods to investigate the noise. Moose can run as fast as 35 miles per hour for short distances, so can outrun most people. If approached by a moose, hikers should put trees between them and the animal — and if a moose charges, climb a tree.

With the decline in moose populations in the Northeast due to climate change and increased winter tick infestation, it is a treat to spot a moose nowadays — from a safe distance. I’ll never forget our close encounter at the pond with that impressive bull.

Susan Shea is a naturalist, writer, and conservationist based in Vermont. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.