By Lee Emmons

As winter approaches and snow coats the ground, the tufted titmouse (Baeolophus bicolor) will again become a ubiquitous backyard visitor. Familiar to even the most casual observers of nature, titmice readily come to feeders, especially those filled with sunflower seeds. Like many other birds that spend winters here, they seem to relish any cold-weather handouts, and I welcome their presence in my yard.

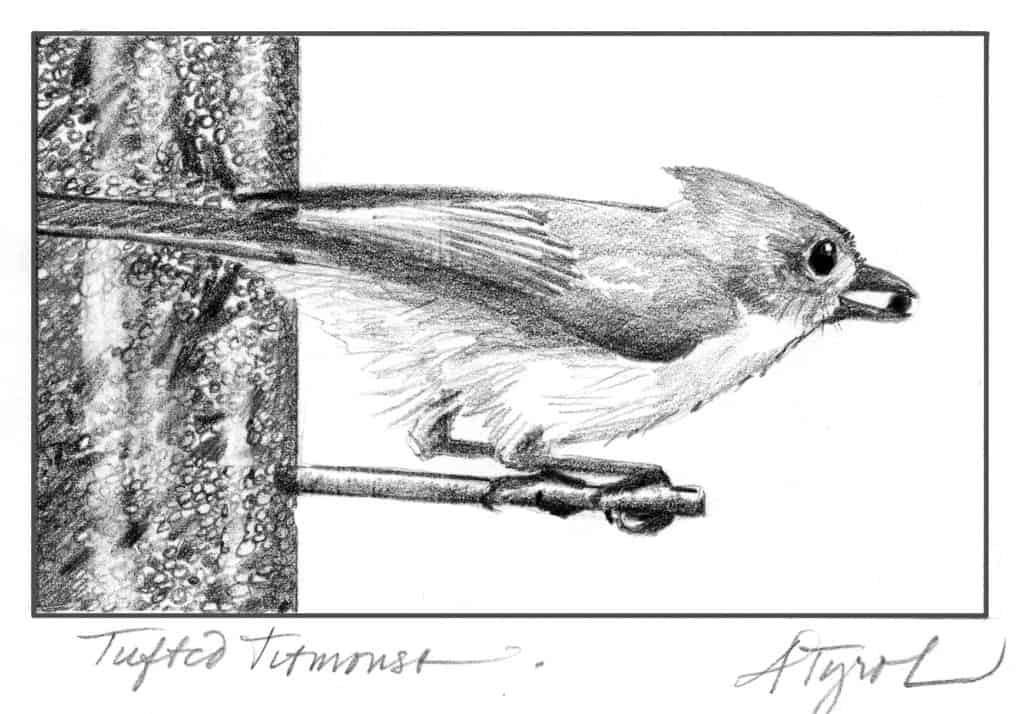

A smallish gray bird with a distinctive crest, both the male and female tufted titmouse have dark eyes, a white belly, and rust-colored flanks. When titmice are out of sight, they can be identified by their peter-peter-peter song. It is a lovely sound, most often heard in late winter and spring. Other vocalizations include nasally, mechanical calls, and titmice are quite vocal in expressing alarm or disapproval.

The tufted titmouse lives in a variety of mixed and deciduous forest types. Titmice also thrive in human-altered habitats such as suburban neighborhoods, city parks, and orchards. Their range stretches southward from Maine to Florida, and westward into eastern Texas. In northern New England, titmice can be found year-round in areas below 2,000 feet in elevation.

While other birds have seen significant population declines in recent years, titmice are both more common and more widespread than they were in years past. American Bird Conservancy estimates a population of 11 million tufted titmice and notes on its website, “At the start of the 20th century, this species was only found as far north as New Jersey and Iowa. Today, it reaches southern Quebec and Ontario.” The tufted titmouse is also prolific in northern New England, where eBird data show about 210,000 observations – more than eastern phoebe, but less than white-breasted nuthatch.

Come springtime, tufted titmice will nest in previously excavated natural cavities or nest boxes. Composed of grasses, leaves, and strips of bark, tufted titmouse nests are cup-shaped and lined with fur or hair. Last spring, I watched as a titmouse removed thick grass clippings from my compost pile; my tedious chore of mowing at least produced some nesting material. Titmice also famously pull hair from unsuspecting people and animals to use for nest construction.

Titmice have one clutch of five to six eggs, with incubation lasting from 12 to 14 days. When the spotted white eggs hatch, the nestlings will remain in the nest for another two weeks, as both parents bring food to the nest. About two weeks after hatching, the young birds leave for the wide world outside the nest. They will move on to new areas to repeat the cycle themselves. However, in some cases, a young bird may stay with its parents to help feed the next year’s brood.

Insect-eaters in summer, titmice will consume ants, beetles, bees, wasps, and caterpillars. Seeds, spiders, snails, and fruit round out their natural diet. Known to gather with nuthatches and chickadees while foraging, titmice will search branches as well as the ground for food. This time of year, the birds cache seeds, usually in tree bark. In your backyard, you may notice titmice prying open some seeds with their beaks, and they seem to enjoy peanuts as well.

Along with chickadees, woodpeckers, and dark-eyed juncos, tufted titmice will increase supplemental feeding as temperatures drop and autumn yields to winter. With natural foods becoming harder to find, sunflower seeds, high-energy suet, and peanuts provide a convenient source of food. As I watch in my backyard, the titmice land on the bright blue hopper feeder. Quickly securing a sunflower seed (they’ll take safflower, too), they dart back into the safety of the trees. Pecking at hanging suet cakes, the titmice stay just a moment longer. With food and cover provided, titmice are content to call my neighborhood home, and I enjoy their visits during an ordinarily dreary time of year.

Lee Emmons is a nature writer, public speaker, and educator. The illustration for this column is by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.