By Karen D. Lorentz

Editors’ Note: This is part of a series on the factors that enabled Killington to become the Beast of the East. Quotations are from author interviews in the 1980s for the book Killington, A Story of Mountains and Men.

“We’ve got a million dollars that says you’ll learn to ski at Killington.”

That million-dollar promise was not an idle marketing ploy. Killington had literally invested a million dollars in the research and development of GLM and its subsequent Accelerated Ski Method, as well as the equipment needed for new skiers in the 1960s and early 1970s. (Part 13 in the May 28 Mountain Times.)

It turned out to be a tremendous investment — $5.1 million in December 2023 dollars (due to inflation)! Most importantly, it worked so well that it turned many newbies, or “never-evers,” into skiers!

Bob Madden had moved to Vermont to work at GE in 1974 when someone told him that Killington was offering a free learn-to-ski week for Vermonters.

“I think it was a masterful plan to get Vermonters on skis and warm up the ski instructors,” he said of his GLM week in December. “We had a delightful young woman who was very good at teaching — a real joy. At the end of the week, I thought the world of her,” he recalled.

Having been a competitive rower and a lover of sports, Madden said he fell in love with skiing that week and bought a pair of skis, which he used for a run on Saturday morning during the first free hour. It was a try-before-you-buy promo that hooked him as he took a run down Snowshed on the beat-up skis he had purchased “without falling.” After skiing on them a few times, John Southworth noted the lack of camber and sold him skis that were more forgiving.

Madden became a volunteer gatekeeper, but he couldn’t ski the steep hill, so he requested the bottom gate so he could walk up. That helped him afford skiing, as he earned a free skiing ticket that afternoon, plus another day’s ticket.

Later, he became an instructor in Pico’s Sunday afternoon children’s program and received a pass, teaching from 1980 to 1985, when he moved again. “I was 28 years old when I learned, and I absolutely loved it. My only regret is I didn’t have the $1,000 to buy a bond in 1974,” he added of a time when such purchases carried a lifetime Killington pass.

More pioneering

But teaching wasn’t the only factor that led to Killington’s popularity and growth. The pioneering spirit that led to the installation of snowmaking and the development of a better way to teach beginners was a company strategy that encouraged many workers to innovate.

Hired as a systems analyst, Charlie Hanley was charged with “finding better ways to do anything. I had free license and could stick my nose in anywhere — my idea of fun.”

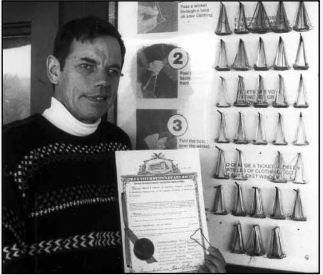

Hanley developed the “ticket wicket” during the summer of 1963. It was an 8-inch piece of high-grade stainless steel wire bent in such a way as to allow the wire to be slipped through a zipper talon, belt loop, or buttonhole. The folded ticket could be stapled over the wicket legs (before the day of computer-printed, sticky-back tickets).

This small device saved the inconvenience of staple holes leaving tears in ski clothing, but just as importantly, it also allowed ski areas to control the switching, sharing, and reselling of tickets. Part of the built-in security feature was a specially manufactured gold-colored staple and a modified staple gun.

In its first season, Killington sold three-quarters of a million ticket wickets to 67 ski areas in the United States and applied for a patent, which was granted on March 22, 1966. The souvenir lift ticket no longer left six holes in a skier’s clothing, and dishonest types found it more difficult to cheat the ski area (and other skiers) because “a better way” had been found. The corporation later sold the ticket wicket business and patent.

Another Hanley brainstorm was the regiscope, a camera device that took a picture of the person renting equipment with his check. “It solved the ski rental theft problem cold because a picture is intimidating to a thief. It worked so well that we never even had to develop the film,” Hanley said.

Ticket Wicket patent

A new snow report

Snow reporting changes introduced by Killington’s founder, Preston Smith, in 1964 were not readily accepted at first. Smith was attempting to eliminate the subjective descriptions “poor, fair, good, and excellent” from ski-area snow reports as he campaigned for the use of factual information and the education of skiers in understanding the reports.

He established a new system at Killington that employed standard procedures for measuring and reporting snow conditions, organizing this information in a compact, simple, and easy-to-understand manner. Under his system, the depth of snow base, type of surface, depth of new snow, air temperature, and weather conditions were given, but the qualifying judgments were not.

This left the individual skier to interpret the facts in light of his skiing ability and knowledge of the area’s terrain, sun exposure, wind, snow surface, and skier traffic.

Part of Smith’s rationale for the new system was to eliminate evaluative judgments, which would vary from skier to skier depending upon skiing ability, preferences, and experience. Then, too, the weather was a variable that could change snow conditions quite rapidly, as could heavy skier traffic.

Killington even ran surveys to compare skier assessments of conditions to their own. They found that, regardless of how the ski area rated its conditions, a significant percentage of skiers disagreed.

Smith noted that this difference of opinion was a significant source of disgruntlement not only among the skiers but also among the media.

Although snow reporting had long been a subject of complaints and a few ski area operators were already interested in the idea of deleting judgments, Smith and Killington were the first to propose and initiate an entirely new system.

It was a risky thing to do, but the sparse snow season of 1964–65 proved to be a good time for the transition. Some questioned the changeover that first season, especially in light of the lack of uniformity of all areas using that reporting system, but many more applauded. The Vermont Ski Areas Operators Association, the Eastern Ski Areas Operators Association, and the New England Council of Ski Areas adopted the new system for the 1965–66 season, with Smith’s half-inch-thick booklet of methods, procedures, terminology, and other information providing the basis for the new snow reporting system. Still, Smith recalled that the effort met with resistance from individual ski areas before becoming the standard in the East several years later.

Innovations like these, GLM, and the adoption of snowmaking were instrumental in attracting attention to Killington, contributing to the area’s reputation, and improving the skiing experience for skiers.

Comments and insights are welcome: email [email protected] to share thoughts about skiing in the 1950s-70s.