The longer, warmer days of spring spark phenological changes in trees, from root to tip. As the limbs of trees stretch and twist toward the sky in search of sun, their trunks grow wider to support the new weight. New wood is added year after year to the cambium, the area of a tree just beneath the bark, where cell division happens. This expansion creates growth rings, also called tree rings. Though growth rings are often hidden from view, the emblematic bullseye pattern can be seen on stumps left behind after felling a tree, or on cut logs strewn across a hiking trail.

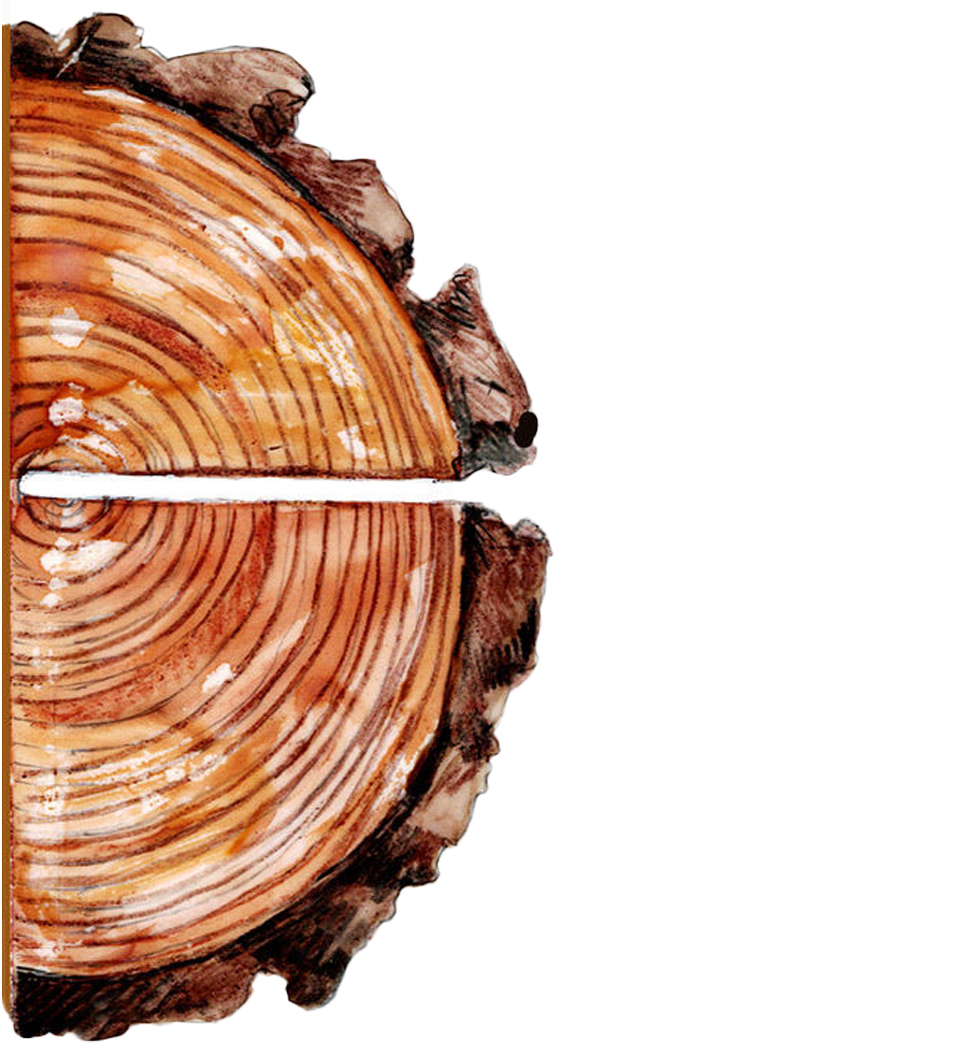

Each ring corresponds to growth in one year. Under magnification, or with the keenest of eyes, they have a visible ombre effect, shifting from light to dark gradually, then abruptly back to light again, reflecting how trees respond to the seasonality of temperate climates.

The wood that cambium produces in spring and early summer is called earlywood. Earlywood is light in color because the cells are large and open to efficiently transport water upward, much like a drinking straw. As the growing season progresses towards autumn, trees prepare for dormancy in winter. They need less water, so their cells get smaller. The constriction of cells results in denser and darker wood; eventually, once winter comes, new cells stop being created altogether. The ombre coloration pattern shows a tree’s slow winding down of biological processes heading into winter, then hitting the ground running when spring rolls back around.

In places with distinct seasonal changes, like the Upper Valley, one ring typically represents one year of life. But in tropical regions, where the climate remains more constant, trees may grow continuously without forming visible rings at all.

To examine growth rings without cutting down or permanently damaging a tree, researchers drill perpendicular to the trunk and extract narrow, pencil-sized cores. Obtaining a core does no more harm than tapping a maple for sap. Tree cores are a powerful tool, allowing scientists to ask and answer questions about growth and climate over extended time spans. Forest ecologists at the Harvard Tree Ring Lab are examining the Northeast’s oldest trees to reconstruct climate fluctuations back to the 1500s.

Recently, through a microscope lens, I counted the rings of a red spruce I first encountered this past summer in Vermont. The rings were so tight together I couldn’t accurately count them in the field with just a hand lens. I tallied the rings in sets of 10, and by the time I finished, I had counted 29 sets and seven rings; the spruce was at least 297 years old, possibly even older. I returned the tree core back to a desk drawer where it sits next to 107 others, all ready to give insight into Vermont’s past.

Another term for examining a tree core is “reading” it, because there is more to the story than just age – tree rings are clues to the life and trials of a tree and the forest in which it grows. My research studying Vermont’s old-growth forests relies on tree rings to understand how forests change structurally with age. When I read a tree core, I count it to estimate age, but I also take note of the tree ring widths. Wide rings represent times when a tree’s light, water, and nutrient needs were all well met, allowing for substantial growth. Narrow rings can indicate a time of suppressed growth due to stressful conditions, such as a drought or competition for sunlight. The tight rings of the 297-year-old red spruce meant its growth was suppressed, competing for sunlight in a dense forest. Other life events marked in cores are fire and insect infestations, which create signature scars.

Growth rings are nature’s diary, chronicling the climate across centuries. While rings record growth internally, bark bears the marks of expansion externally. The new wood added year after year generates a width the bark must expand to accommodate. Dr. Alexandra Kosiba, UVM Extension assistant professor, explained that the bark gets ripped apart, then generates new cells to repair where cracks occur. This ripping and repairing creates the craggy, deeply furrowed appearance of old trees. They’re like stretch marks: an external echo of the story within.

The history we can learn in growth rings is only possible thanks to our cold winters and warm summers. As we march towards summer, trees continue their seasonal cycle, writing their story in wood.

Alyssa van Doorn is a naturalist and forest scientist from South Burlington, Vermont. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.