Fractals are sometimes referred to as a “visual representation of math.” They can be observed in the spatial arrangements found in many familiar forms, patterns, and shapes in nature: from the branching of trees, ferns, river systems, and lightning to the patterns found in leaves, seedheads, crystals, seashells, snowflakes, clouds, hurricanes, and geologic terrain. The intricate branching patterns of blood vessels and respiratory structures are some intimate expressions of fractals in animals.

As a fractal grows, the pattern replicates itself on a larger scale. The German mathematician Felix Hausdorff laid the mathematical foundation for our understanding of fractal geometry during his groundbreaking work modeling the mathematics behind geometrical shapes and patterns. In 1918, Hausdorff introduced the Hausdorff [fractional] dimension, a model that shows how to calculate the dimensions of spatial patterns that replicate or repeat at different scales.

The word “fractal” was first used in 1975 by Benoît Mandelbrot, a French-American mathematician, who described intricate shapes and patterns that repeat even when an object is viewed at different levels of scale. Mandelbrot defined a fractal as “a rough or fragmented geometric shape that can be subdivided into parts, each of which is (at least approximately) a reduced-size copy of the whole.” Whether you are looking at a fractal zoomed in or from a distance, each view resembles the same pattern.

Ferns are among the best and most accessible examples of fractals. The leaves of each fern, which are called fronds, form the self-same pattern when viewed at any distance or scale. In fact, one of the most well-known formulas in fractal geometry is the Barnsley fern. In his 1988 book, “Fractals Everywhere,” Michael Barnsley, a British mathematician, describes how he created this fractal to simulate the frond of black spleenwort (Asplenium adiantum-nigrum), a common European fern.

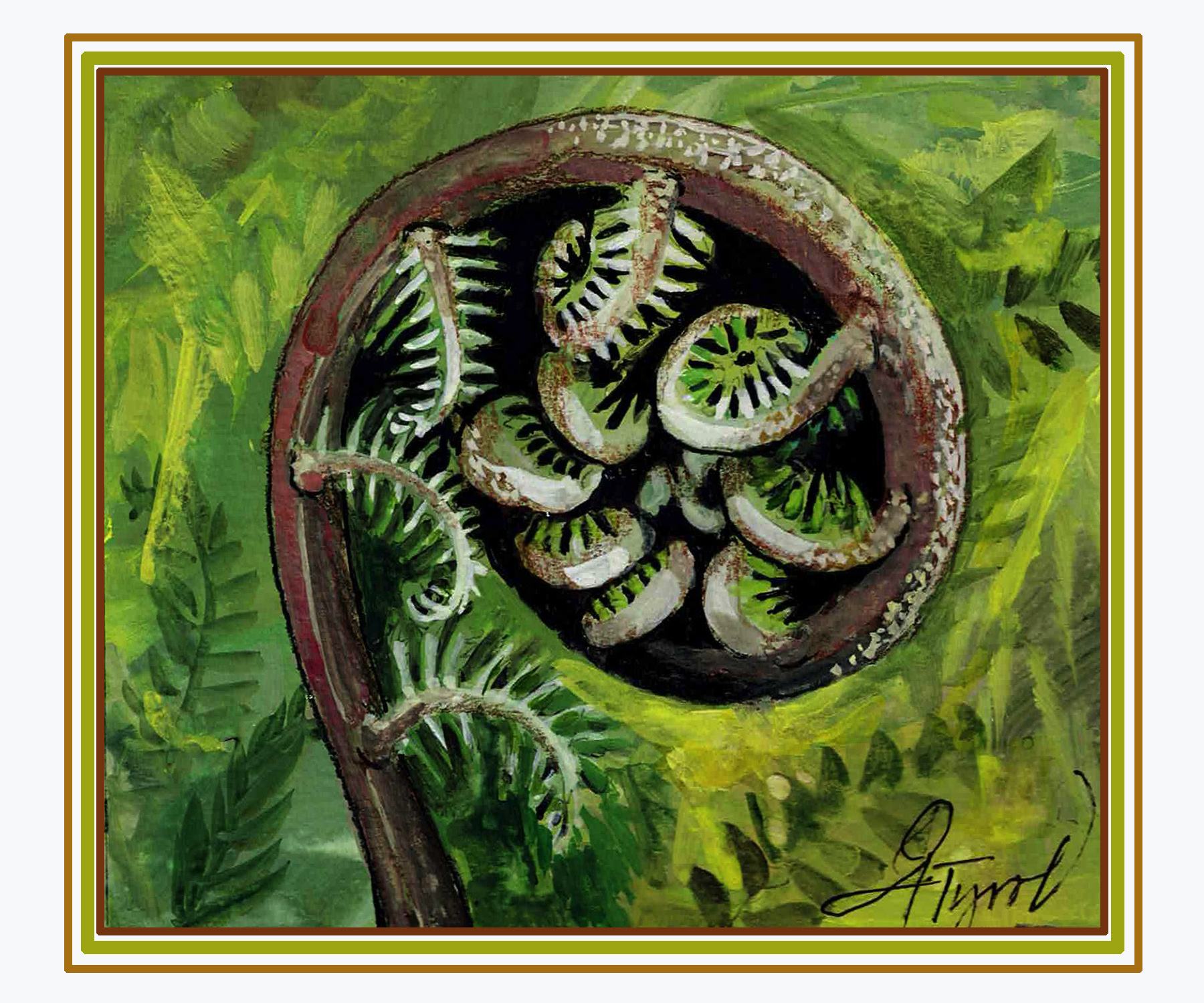

The fiddlehead pattern of a sprouting fern is a perfect example of a fractal. The familiar fiddlehead is a classic shape that—along with the similarly spiral-shaped nautilus—has inspired countless works of art and sculpture, from the carved spirals at the tops of violins and other stringed instruments to the ingenious spiral staircases in the designs of the iconic Spanish architect Antonio Gaudi and even the spiral path at the start of the Yellow Brick Road in “The Wizard of Oz.”

The petiole, or leaf stalk, forms the spiral-shaped fiddlehead of a sprouting fern as it unfurls into a frond. As the leaf stalk grows, each pinna, or leaflet, at first appears as its own minute fiddlehead. The next time you look at a lacey fern frond, try focusing gradually closer, and you will see how the overall pattern created by the entire frond is repeated in each of the gradually smaller elements that branch off of it.

Of course, not all ferns are intricate laceworks. Walking fern(Asplenium rhizophyllum), which is rare in most of the Northeast, has undivided fronds. Other fern fronds, including those of sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis), are simple divisions off of the main stem. Fronds of the ethereal maidenhair spleenwort (Asplenium trichomanes) have individual pinnae branching off each striking black stem. The fronds on some ferns, such as long beech ferns (Phegopteris connectilis), are divided two times, while the most delicate ferns, including evergreen wood ferns (Dryopteris intermedia), are divided three times.

Two of my favorite examples of how nature weaves the threads of geometry into beautiful green tapestries are the lacey arching fronds of northern maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum), which grows in moist, shady woodlands, and the tall, lush, bushy masses of royal fern (Osmunda regalis), which commonly grows in and along wetlands. Both are found throughout New England.

The variety of shapes among ferns reveals that there are many examples of fractals found in the natural world. These are visually striking expressions of the hidden geometry that lend order to the fascinating forms we see. As the ferns begin unfurling this season, take a moment to contemplate their patterns and reflect on fractals.

Michael J. Caduto is a writer, ecologist, and storyteller who lives in Reading, Vermont. He is the author of “Through a Naturalist’s Eyes: Exploring the Nature of New England.” Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.