By Susan Shea

On a walk one winter afternoon, I spotted two white objects darting across a snow-covered field. White on white, they were difficult to identify at first. It was a short-tailed weasel chasing a snowshoe hare!

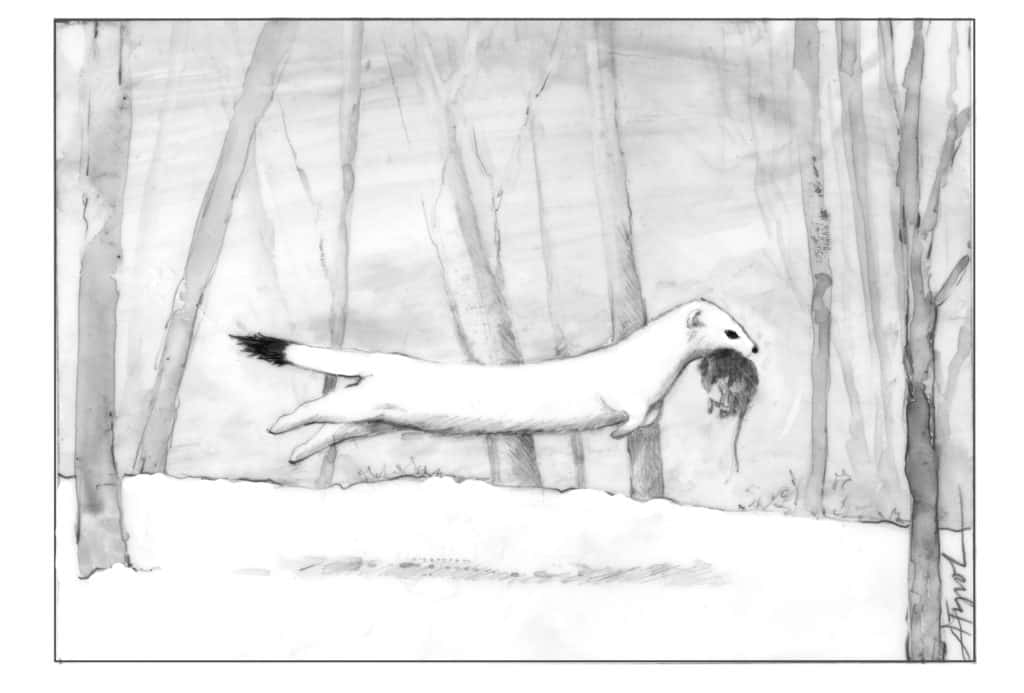

Apart from the snowshoe hare, short- and long-tailed weasels are the only animals in the Northeast whose coats turn white in preparation for winter. The smaller short-tailed weasel, also known as an ermine, is more common than the long-tailed weasel. It lives in a variety of habitats, is an adept hunter, and has a reputation for being curious and bold.

In summer, the short-tailed weasel is brown with a cream-colored chest and belly, and a black tail tip. In the fall, in northern latitudes, the ermine sheds its summer fur and grows a white winter coat. This amazing adaptation camouflages the weasel as it hunts, and hides it from predators such as hawks, owls, foxes and coyotes. The black tail tip, which remains in winter, diverts predators. A raptor attracted to a weasel’s movement will dive at the black tip, missing the weasel’s body.

In the spring, the ermine loses its white coat and turns brown again. Both molts are triggered by photoperiod, or length of daylight. Vermont naturalist Susan Morse once raised an orphaned weasel for release back into the wild. She enjoyed watching the ermine’s coat turn white, which began on lower parts of the body first and took seventeen days. However, this adaptation may become a problem for weasels as the climate warms, and snow cover becomes inconsistent in our region. White weasels will be much easier to spot against a brown background and will be more vulnerable to predators.

Researchers in Poland found that populations of the white subspecies of the least weasel (cousin to our short-tailed weasel) dropped with a decrease in the number of days of snow cover. Experiments showed predators detected weasels with contrasting colors at a significantly higher rate than those that blended in with the landscape. If our northern weasels can adapt through natural selection, where snow is brief or erratic, they may develop patchy coats. Alternatively, populations may include both white and winter brown animals, as is already the case in mid-Atlantic weasel populations.

Short-tailed weasels feed primarily on voles and mice, and occasionally on larger prey such as chipmunks, squirrels, or even hares – which explains the snowy chase I observed. In summer they prey on nesting birds and their eggs, frogs, and insects; they also eat berries. Some ermines will kill chickens, though a weasel will often visit a chicken coop only to prey on the rats and mice attracted to the chicken feed.

Their long, thin shape enables weasels to travel through rodent tunnels and kill their prey in their underground burrows – or, sometimes, within a human dwelling. My sister once lived in an old farmhouse that became infested with mice. She and her roommates had a contest going to see who could devise the most ingenious mousetrap, and they kept a tally of how many mice were killed. Then an ermine moved in with them for a month. “We didn’t have much of a mouse problem after that,” she recalled. “The ermine would come up from the cellar under the door and slither along the kitchen countertops.”

Sometimes a weasel will live in a mouse den until all the occupants are consumed. Weasels often kill more than they can eat and cache dead prey for later use. “They strive to always have something in the pantry,” said Morse. “People routinely find stored mice in the crevices of their wood piles.”

While the weasel’s shape contributes to its hunting prowess, it also causes the animal to lose heat more quickly than a more rotund creature. To compensate, the ermine has a high metabolic rate and must eat one-third to one-half of its body weight a day, making it perpetually hungry. For this reason, ermines are active even in the coldest weather, especially at night. Weasels hunt primarily by scent, zig-zagging back and forth, investigating every hole and cranny.

This winter, look for weasel tracks in the snow – small, paired tracks with five claws on each foot. Since weasels travel by bounding, their hind tracks fall directly on top of their front tracks. Also, keep an eye out for the weasel’s long, spiral-shaped, blackish-brown scat on rocks in the center of the trail, scent posts to communicate with other weasels.

A version of this article was originally published in the Long Trail News. Susan Shea is a naturalist, conservationist, and freelance writer who lives in Brookfield.. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation.