By Lee Emmons

The brown thrasher (Toxostoma rufum) lives out its days in relative seclusion. Like the gray catbird, which has a similar fondness for thickets and shrubby areas, brown thrashers haunt areas of dense cover, although discerning eyes may be able to spot these birds within that habitat. Even when they’re out of sight, brown thrashers may be heard singing loudly in late spring and early summer, often incorporating bits of other birds’ songs into their own.

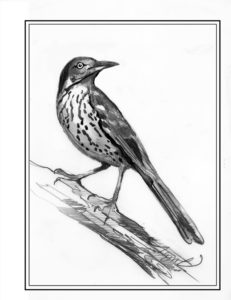

Measuring between 9 and 12 inches from bill to tail, brown thrashers are reddish brown in color, with two white and black bars on each wing, and dark streaks along a whitish breast. They sport a long tail, downcurved bill, strong legs, and vivid yellow eyes. Despite weighing only 2 or 3 ounces, brown thrashers are considered to be large by songbird standards. Juveniles are similar to adults, but their eyes lack the distinctive yellow color.

Ranging east of the Rockies, from southern Canada to the Gulf States during the breeding season, brown thrashers arrive in northeastern forests in spring and depart in late summer. They live year-round in the southeastern states, and the brown thrasher is the state bird of Georgia.

Brown thrasher habitat includes thickets, brushy fields, forest edges, sheltered areas near farms, blueberry barrens, and hedgerows. In “Familiar Garden Birds of America,” Henry Hill Collins Jr. and Ned R. Boyajian note, “This species is best distinguished by its skulking habits. It spends most of its time in dense tangles and underbrush and, while not difficult to locate, is not seen much in the open.” Brown thrashers will also visit backyards and neighborhoods with adequate cover and suitable nesting sites.

Thrasher nests are often located several feet above the ground in a shrub or small tree. Nests have also been documented on the ground in areas of protective cover. A platform of sticks protects a cup lined with rootlets and grass. Built by both sexes, the nest supports a clutch of up to five blue-white eggs. The entire process of incubation takes about two weeks. Brown thrashers are known for aggressively protecting their nests from predators such as snakes and hawks.

Brown thrashers forage on the ground by probing and turning organic debris with their curved bills. They also chase insects, favoring caterpillars and beetles, and adding grasshoppers and wasps, along with tree frogs and young snakes to the menu. The birds also consume a variety of fruits, including strawberry, blueberry, grape, and Virginia creeper. According to Chris Earley’s “Feed the Birds,” brown thrashers will come to feeders that offer suet, fruits, mealworms, and cracked corn.

Though fairly common in areas with appropriate habitat, brown thrashers are decreasing across most of their range. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, habitat loss and degradation is the main threat to these birds, as former agricultural areas revert to forest, and shrub-covered thickets are cleared. Threats posed by pesticides and collisions with structures during migration also negatively impact the population. Citing declining numbers and multiple threats, 11 northeastern states have listed the thrasher as a species of greatest conservation need.

There are a variety of habitat considerations to conserving brown thrashers. The University of New Hampshire recommends woodlot owners maintain a high percentage of trees in the sapling and pole stages and schedule treatments to provide these habitat conditions over time. They should also avoid work in these areas from April to June, during the thrashers’ breeding period.

Backyard birders may attract thrashers by providing dense cover, including shrubs that produce berries, and offering fresh water through a birdbath or other water feature.

Like other birds, brown thrashers rely on dependable habitats where they can secure food, cover, and nesting sites. Retaining shrubby areas or creating such places will help attract this species to your backyard or property – and help brown thrashers survive in a challenging time for birds.

Lee Emmons is a nature writer. The illustration for this column is by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org. This piece received additional support from the Arthur Getz Trust, Citizens Bank, N.A., Trustee.