By Catherine Schmitt

Some things are so familiar, so common, that they are often overlooked. Such is the case with northern white cedar (Thuja occidentalis). Also known as eastern white cedar, this tree grows throughout the Northeast, but only in certain places, in part because it has evolved many ways to live and grow that other trees have not.

A boreal tree, the cedar’s way is cold. It grows in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, northward as far as the edge of the tundra, and southward in isolated pockets where local climate conditions are cooler.

One of the cedar’s ways is wet, its shallow roots grasping the edges of dark streams and lake shores, sinking into soggy ground thick with moss. Cedars lean as often as not – they don’t seem to mind a bit of slant. As long as groundwater flows enough to circulate nutrients and oxygen, they will thrive in the swamp.

Another way is dry. Northern white cedar is equally at home on rocky hillsides and limestone cliffs, the roots taking on serpentine forms as they draw calcium from stone and soil. Northern white cedars have also come to live as sculpted forms at the edges of parking lots, trimmed hedges between neighbors, and ornaments of yards and gardens.

Cedar is persistent. Of all the trees in the Northern Forest, cedar lives the longest —three or four hundred years is typical. In some rare, remote places, such as on the steep walls of the great escarpment that ends at Niagara Falls, cedars can live more than 1,000 years.

It hasn’t had many chances to live this long, however, as the resinous wood’s resistance to rot makes it useful for fencing, housing, roofing, piping, and boating. The fragrant wood splits easily and makes good kindling. Branches, when burned, lend smoke to Abenaki prayers and ceremonies.

Tolerant of sun and shade, the cedar’s way is mostly slow. Even in the best growing conditions, it can take centuries to reach large sizes. The largest cedars, 4 or 5 feet in diameter, tend to be found in old, unlogged forests. But old trees are not necessarily big trees; an 80-year-old cedar may only be 4 inches in diameter. Age is also hard to estimate, because cedar tends to rot from the inside out, making tree-ring cores unreliable. Instead, scientists look among the rings for growth spurts that indicate a canopy-opening disturbance they can link to a recorded hurricane or other wind storm.

Wind is another way of the cedar, creating clearings in the woods that allow saplings to accelerate growth and reach the canopy. Wind carries pollen from male to female flowers, which grow on the same tree, and scatters the winged seeds across the forest, where they take root on rotting stumps or talus slopes.

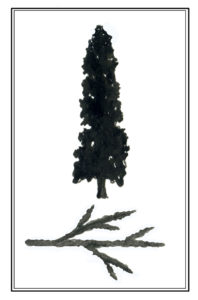

A riot of young cedar saplings can appear to sprout straight from water or bedrock. Branches form low on the trunk. A branch that touches the ground will sprout a new tree. Other branches curve upwards in a tangle of feathery foliage, light green taking on a yellowish tinge with age. A mature tree has a rounded conical shape.

Flat sprays of scale-like leaves reveal its membership in the cypress family and contain the Vitamin C that may have inspired the alias “arborvitae,” which means “tree of life.” Sipping cedar tea can clear the respiratory system and was a traditional drink to ward off scurvy. Northern white cedar is known for healing wounds, recovering nerve damage, boosting immunity, calming the psyche.

Cedar is a favorite of white-tailed deer all year long, but especially in winter when they shelter in dense stands of cedar. Fine shreds of northern white cedar bark line the nests of crows, sharp-shinned and red-shouldered hawks, and the long-eared owl. Cedar forests are home to flycatchers, crossbills, waxwings, Cape May and yellow-rumped warblers. Three-toed woodpeckers nest in dead cedar snags.

Cedar bark is fibrous, reddish, but quickly weathers to light gray, blotchy with lighter gray lichen and green with liverworts and feather mosses. Cedar bark often twists around the trunk, revealing a spiral growth pattern, like a tarnished silver tusk. Is it the wind pushing on the thicker south side of the tree? Or the tree’s way of equally distributing nutrients or adding flexibility? The turn of the Earth? Or simply another of the cedar’s many, many ways?

Catherine Schmitt is a science writer and author of “The President’s Salmon: Restoring the King of Fish and its Home Waters.” Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.