By Laurie D. Morrissey

I’ve seen all kinds of birds on the wooded New Hampshire hilltop where I live, but never – until recently – a duck. So when I spotted a pair of wood ducks loitering in my yard one spring morning, I reached for the binoculars. A closer look revealed these were indeed Aix sponsa, newly returned from their wintering grounds. Most likely it was the pair I had seen on the pond a mile from my house. But what, I wondered, were these dabbling ducks doing up here?

It turns out that it is not uncommon for wood ducks to nest a half mile or more from a pond or stream, and they often nest near areas such as wooded swamps and vernal pools. Although the vernal pool in my woods is only about the size of a large kitchen, it could be this pair’s summer home. Furthermore, my mixed-hardwood forest provides good eating. Besides aquatic foods, wood ducks eat nuts, including acorns and beech nuts. They especially like white oak acorns, which are sweeter than those of red oak.

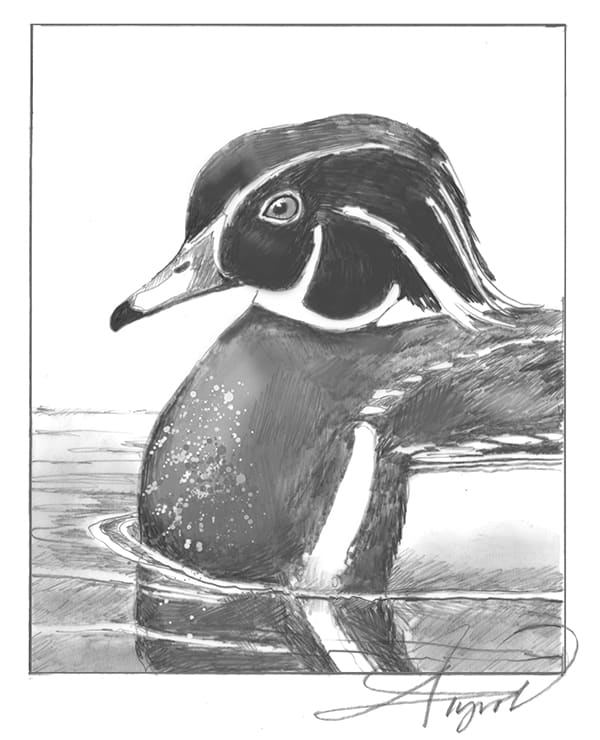

No matter where you find them, woodies are a welcome sight, and easy to identify. The wood duck is smaller than a mallard and has a shorter bill. The distinctive plumage of the drake includes pale sides and a chestnut breast, with black and blue feathers on its back, tail, and wings. Its glossy green head has a long crest and bold white facial markings. By late summer, the male’s plumage will be subdued, although he’ll retain his distinctive “chinstrap.” Hens, conversely, are grayish-brown, their most noticeable feature being a teardrop-shaped white eye-ring.

Wood ducks begin arriving in northern New England in March. After finding the perfect tree cavity or nest box (often the same one used the previous year), they produce a clutch of eight to15 eggs. Wood ducks commonly engage in egg-dumping, when a female lays her eggs in another duck’s nest and leaves them to be raised by the surrogate female. Nests are above ground, from 2 feet to 60 feet high, and chicks leave the nest at the ripe old age of one day by leaping from the entrance.

Wood ducks begin arriving in northern New England in March. After finding the perfect tree cavity or nest box (often the same one used the previous year), they produce a clutch of eight to15 eggs. Wood ducks commonly engage in egg-dumping, when a female lays her eggs in another duck’s nest and leaves them to be raised by the surrogate female. Nests are above ground, from 2 feet to 60 feet high, and chicks leave the nest at the ripe old age of one day by leaping from the entrance.

Once one of the most abundant waterfowl in North America, wood ducks were nearly extinct by the early 1900s due to habitat loss and market hunting. Their recovery, thanks in large part to the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, is a wildlife conservation success story, and there are now an estimated 3 million breeding pairs across North America.

Part of this success is attributed to volunteer citizen scientists, including Jim and Noah Wistman. Canoeing on a pond in northwestern Connecticut about 13 years ago, the father and son discovered one of the first wood duck nesting boxes installed by the state’s wildlife division in the 1950s. The pair soon became knowledgeable advocates for reintroducing a breeding population of Aix sponsa to their area, where they had only been passing migrants for some years.

The Wistmans have since built, installed, and monitored dozens of boxes on protected wetlands, providing housing for hundreds of downy wood duck chicks. It is a year-round effort: when the ponds freeze, they load their canoe with tools and other equipment and haul it over the ice. They clean out existing boxes (often used by mice, owls, and flying squirrels) and put in clean wood shavings. They look for down feathers and bits of eggshell, and send field reports to the state wildlife agency.

In New Hampshire, Fish & Game biologists monitor about 300 wood duck nesting boxes in state wildlife management areas. They gather critical data while cleaning the boxes, which are also used by hooded mergansers. These data are shared with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, which works with states to set bag limits for Atlantic Flyway waterfowl. Unfortunately, well-intentioned citizens sometimes beat biologists to the boxes, leaving tidy floors with no telltale eggshell fragments or unhatched eggs.

Biologists now mark the boxes with Do Not Disturb signs and discourage this activity on state properties, according to Fish & Game Wildlife Biologist Jessica Carloni. However, she encourages people to put up boxes on their own property and clean them out as a favor to wood ducks. After all, these ducks have lots of admirers. It’s easy to see why.

Laurie D. Morrissey is a writer who lives in Hopkinton, New Hampshire. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.