By Susan Shea

During winter, I catch glimpses of crows as they fly swiftly over our valley, cawing, or gather in small groups to feed on roadkill along the highway. Sometimes I find their wandering tracks leading to holes in the snow where a crow probes for food. These sightings have made me curious about how these large birds survive the winter.

Most crows that breed in Canada and far northern Maine migrate south, some stopping in other areas of the Northeast to join local flocks. Crows that nest in our region often travel short distances to spend the winter. A 2018 study led by Andrea Townsend of Hamilton College fitted crows in New York State with satellite transmitters to track their movements. Crows in the study migrated an average distance of 310 miles and returned to their breeding territories in spring. Some remained on their territories year-round. The migratory crows were flexible from year to year about where they spent the winter.

Crows use a wide variety of habitats, but prefer open landscapes for ground-feeding with nearby woods for perching and roosting. They frequent garbage dumps in towns and cities. Crows tend to stay away from large forested areas and high elevations where their larger cousin, the raven, is common.

Omnivorous and opportunistic, crows feed on a diversity of plants and small animals. In winter, crows consume grain, seeds, nuts, and fruit, supplemented by carrion and garbage. Like hawks and owls, crows regurgitate indigestible materials such as bones in pellets. Intelligent and alert, they will steal food from other crows and other animals. Crows have even been seen pulling a cat’s tail to distract it from its food. When they happen upon a bonanza of food, these birds will cache some of it for later, concealing it from others. In his book “Ravens in Winter,” biologist Bernd Heinrich writes that he spent two hours watching a pair of crows make 44 trips to cache fat from a piece of meat he had placed outside his cabin in the Maine woods. Crows have also been observed using and even fashioning tools to obtain food, for example, shaping a stick to poke into a hole and pulling out insects.

Crows are highly social birds, and families live together year-round. The young remain with their parents for a few years and help raise the new nestlings. Heinrich observed groups of crows feeding amicably together on his meat baits in Maine.

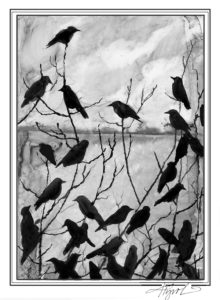

In winter, large flocks of both resident and migratory crows may roost together at night. Biologists Kent McFarland and Sara Zahendra of the Vermont Center for Ecostudies followed thousands of crows to a night roost in pines near West Lebanon, New Hampshire, in the winter of 2017. The crows began gathering in small groups a couple of hours before sunset in pre-roost trees, then streamed towards the roost like a black river. Communal roosts provide more eyes and ears to detect predators such as great horned owls, known to swoop through crow roosts at night. The body heat generated by multitudes of birds makes temperatures in the roost warmer. Communal roosts may also serve as information centers for finding food and mates. Around dawn, crows leave their roosts, flying in many directions to forage.

Crows may use the same winter roost for many years. A survey of communal roosts in New York State discovered six roosts that had been used for more than 40 years and one roost in use for more than 125 years. The number of birds in the roosts surveyed ranged from a few hundred to 2 million. The massive roosts were located in areas with abundant food. In recent decades, more crows have been roosting in urban areas, including spots with artificial lights, which predators tend to avoid. In Vermont, communal roosts have been reported in Burlington and Middlebury.

Crows have long been viewed as a nuisance because of the crop damage they can cause, their habit of preying on the eggs and young of other birds, and the noise and mess of large roosts. Today, however, there is recognition of their role in insect control and more appreciation for their intelligence and adaptability, although crow hunting is still permitted in many states.

Susan Shea is a naturalist, writer, and conservationist based in Vermont. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.