By Lee Emmons

On winter mornings, I often venture outside to photograph the assembly of birds that visit the feeders in my front yard. One of the regular visitors is the diminutive downy woodpecker, which clings to my peanut feeder, takes a nibble of suet, or forages in the nearby maple trees. Fairly comfortable with a human presence, these birds feature heavily in my photos.

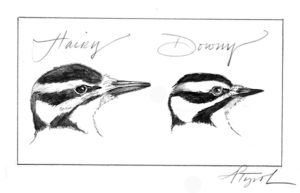

Measuring only 6 inches in length and weighing less than an ounce, downy woodpeckers are the smallest of North America’s 22 native woodpecker species. They are often confused with the similar-looking hairy woodpecker. Downies are smaller than hairy woodpeckers, however, and rather than the hairy’s spike-like bill, downies sport a smaller, less conspicuous bill. Males possess a red spot on the back of the head, and both sexes have a general black and white appearance.

I’m hardly alone in seeing these woodpeckers, especially during the coldest months of the year. Found in every state except Hawaii, and throughout much of Canada, downy woodpeckers are abundant across North America. Associated with riparian habitats and deciduous forests, downies are also present in suburban parks, developed neighborhoods, orchards, and mixed woods. In the Northeast, the species is a regular visitor to backyards with bird feeders and tree cover.

Although they are not long-distance migrants, downy woodpeckers in the northern part of the range and in mountainous areas do move in winter. In the “Peterson Reference Guide to Woodpeckers of North America,” Stephen A. Shunk writes, “These birds tend to move southward or downslope as the frost level lowers in elevation, often overwintering in urban woodlots and frequently visiting well-stocked feeding stations.”

Downy woodpeckers also adapt to winter weather by changing their foraging habits. As Bernd Heinrich relates in his book “Winter World,” downy woodpeckers may join a flock of chickadees which might also include brown creepers, red-breasted nuthatches, and golden-crowned kinglets. These mixed species flocks enable member birds to avoid predators and take advantage of available food resources.

During winter, male and female downy woodpeckers also feed in different places. Females are relegated to the lower portion of trees, while males forage higher up. However, both males and females continue to find insects by drilling into tree bark. Once they’ve made a hole, downies use their long, barbed tongues to extract hidden insect prey. Depending on the time of year, preferred foods include gall wasps, caterpillars, and wood-boring beetles. At winter feeders, sunflower seeds, peanuts, and suet are all readily eaten. In the spring and summer, downy woodpeckers have also been spotted sipping from hummingbird feeders.

To stay warm on frigid nights, downies roost in cavities they’ve excavated in dead or dying trees. Constructed in late fall, these spaces offer shelter from sub-freezing temperatures and protection from predators. Downy woodpeckers will also use artificial nest boxes. After the sun rises each day, a woodpecker will vacate the roosting site and begin searching for food.

Downy woodpeckers rely on a variety of woodland types to meet their food, water, and cover needs. They thrive in regenerating open forests as well as towns and cities with adequate tree cover. However, like other woodpeckers, downies rely on snags for nesting during the breeding season. Removal of these dead trees may negatively impact local woodpecker populations. Development that fails to leave pockets of trees will also reduce suitable habitat.

In my yard in southern Maine, downy woodpeckers join the chickadees, titmice, nuthatches, and hairy woodpeckers that wait for a turn at the feeders. Small yet easily spotted, these woodpeckers are well-suited to life in a Northeastern winter. I appreciate their ingenuity and their ability to stay warm and fed during the most challenging time of the year. And on a personal level, I appreciate the inspiration they afford me day in and day out.

Lee Emmons is a nature writer. He lives in Newcastle, Maine. The illustration for this column is by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: www.nhcf.org.