By Dom Cioffi

During one of my late-night forays into the depths of YouTube, I stumbled upon a video of a guy playing individual keys on a piano while his young son, who had his back turned, rattled off the identifying notes. Once they finished with individual keys, they moved onto chords, whereby the kid flawlessly named all the notes in each chord his father played.

The young man was not only able to name each note in a variety of involved chords, but could also easily hum whatever note his father suggested. Imagine someone saying to you, “Hum a B augmented over a D flat augmented,” and then be able to instantly produce that tone with your mouth. For 99.99999999% of the world’s population, that is simply impossible.

I quickly realized I had stumbled upon an impressive display of perfect pitch, which is a very uncommon trait.

Perfect (or absolute) pitch is the rare ability to be able to hear notes or chords and, without reference, be able to identify them by name. It’s a stunning thing to watch, but even more stunning when it’s accomplished by someone so young.

I was intrigued by the video, so I looked at the guy’s YouTube channel to see what he was about. It turns out that he was a reputable record producer who had begun posting videos online to expand his teaching programs. He had several other videos on a variety of topics, so I decided to watch a few.

And that’s how I came to know and love Rick Beato, a middle-aged guy from New York who now resides in Atlanta, Georgia, where he runs a small recording studio.

Beato has almost 2.7 million followers on his YouTube channel (that’s an impressive number for those of you who have no reference). His command of music both as a musician and as a teacher is remarkable. But what really makes his content interesting is his commentary on popular songs and musicians. Using his formidable knowledge, Beato can convey very complex musical ideas into tiny, discernible pieces.

I’ve learned more from Rick Beato in the last two years than all my previous years of studying theory on my own.

In fact, I’ve always been a bit of a nerd when it comes to the nuts and bolts of music. I never formally studied music theory in school, but it was something that intrigued me enough that I bought books to understand it better. Initially, I thought knowing music theory would make me a better musician (and it definitely will), but as I learned more, I simply became intrigued by how complex music can be, and how beautifully structured it can be behind the scenes.

I’ve always looked at it like this: When I hear a beautiful or catchy song, I get attached to it. And when I get attached to it, I want to know more about it, so I lift the hood and start poking around. I look at the chord structure, the way the melody floats along, the time signature, what the individual instruments are doing, and anything else that catches my ear.

Sometimes I’m in awe of the simplicity of a song and can’t believe that something so sparse can sound so alluring. And other times I’m dumbfounded at the immense craftsmanship put into a song and how the writer ever stumbled upon such unique chord combinations.

When my high school friends and I decided we wanted to start a garage band, we knew virtually nothing about music theory and even less about how to play, but we were determined to do it. I knew we had to have a simple song to start with so I scrambled through some old chord books and decided “Eight Days a Week” by the Beatles would be our best bet.

Weeks later (and after a lot of practice), we were able to eke out a version of that song that was borderline adequate. After that, I was hooked — both on the Beatles and playing music.

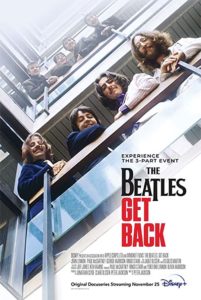

This week’s film, “Get Back,” the much-heralded documentary from Peter Jackson that highlights restored footage from the “Let It Be” recording sessions in 1969, gives the viewer a glimpse into the creative process as the Beatles and their tight-knit entourage scramble to put together their next album.

Imagine that you have three weeks to write, record, and produce an album (which is absolutely insane by today’s standards), and the whole time you’re going to have video cameras recording everything that happens. That’s what the Beatles agreed to with this project.

“Get Back” is not going appeal to everyone since it’s mostly footage of four guys in a large room writing songs, but if you’re musically inclined or have a deep appreciation for the Beatles, then this film is going to feel like heaven on earth.

A historical “A” for “Get Back,” available with a subscription to Disney+.

Got a question or comment for Dom? You can email him at [email protected].