By Frank Kaczmarek

What do the following items have in common: the Declaration of Independence, Da Vinci’s notebooks, Bach’s musical scores, Rembrandt’s drawings, Shakespeare’s plays, and the Magna Carta? Give up? These examples, along with countless other documents ranging from the historically important to the more mundane, were all recorded using iron gall ink, which is made — in part — from the protrusions created after oak gall wasps lay their eggs within oak trees.

Ink was first used in the Middle East and Asia around 2,500 B.C. This early ink was created by mixing soot containing pure carbon with gum to keep the carbon in suspension. While carbon ink would not fade or discolor with age, it did not penetrate into paper and could easily be smudged or removed. In contrast, iron gall ink binds to paper as it sinks in, making it indelible. This was the ink of choice in the Western world from medieval times until well into the 19th Century.

Galls are abnormal, tumor-like formations that can occur on any part of a plant, from the tips of roots to stems, leaves, and flowers. They are commonly named according to their appearance, for instance apple gall, hedgehog gall, spiny gall, fleshy gall, and potato gall.

Fungi, worms, and mites can all cause these abnormalities, but insects are responsible for the lion’s share of galls. Each insect species generates a gall distinctive in both size and shape. Insect galls also vary by which part of plant they form on. Tiny cynipid wasps cause many types of galls found on oak trees.

A gall arises from a wound made when an insect lays its eggs. Once the eggs have hatched, the insect larvae secrete one or more chemical irritants that interfere with the plant’s normal physiology. The enlarging gall surrounds the insect larva with plant tissue, sealing it off from the outside world and providing it with room and board. Tannic acid hardens the gall’s outer wall, while the nutritious inner tissue layer serves as the food source for the larva.

Tannic acid, the same chemical that gives red wines a level of astringency, is bitter and is toxic to many microbes. It binds strongly to proteins and may act as a deterrent to some plant-feeding animals and insects. Tannic acid also has the ability to combine with iron salts, forming a blue-black precipitate.

Among the thousands of different types of galls, those found on oaks are most often used for ink production. There are more than 800 species of gall wasps in the United States and Canada, and roughly 70% of them produce galls on oaks. Oak galls are rich in tannic acid, and many different types of oak galls can be used to make ink.

While there are numerous recipes for making iron gall ink, the process is simple and relies on the same basic ingredients. Galls are pulverized and placed in boiling water to extract the tannic acid. Iron sulphate is dissolved in the gall mixture, creating a bluish-black color complex. Then gum arabic, obtained from the acacia tree that is a native to some regions of the Middle East, is added. Gum arabic aids in the smooth flow of the ink and acts as a binding agent of the ink to the paper’s surface. The final step in making the ink is to strain the solution through something like cheesecloth to remove large particulates.

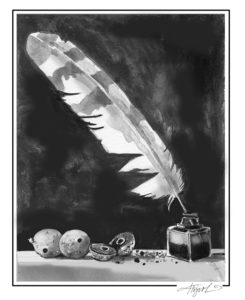

When I was an adjunct college instructor in Connecticut, I had my classes make iron gall ink following a recipe originally published in 1571. Students collected galls from white and red oaks growing in a nearby forest. They fashioned pens from reeds and turkey or goose feathers and used the materials to complete several writing assignments. Hopefully, the students came away with an appreciation for the enormous impact a tiny wasp had on human culture. It would have galled me if they hadn’t.

Frank Kaczmarek is a photographer and retired biologist and author of “New England Wildflowers: A Guide to Common Plants,” a Falcon field guide published in 2009 by Globe-Pequot Press. He lives in Lyman, New Hampshire. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.