By Rachel Sargent Mirus

As we stroll down a forest trail, we pass trees of all types and sizes, with red and orange and brown leaves strewn below, a riot of ferns fading to yellow, and intermittent moss-covered rocks. Amongst this profusion of forest growth are stumps and fallen logs: what will become new soil for a future forest. I’ve always wondered at the varying hues of this woody debris; decaying wood can range in color from orangey-brown to nearly white, from black to bright teal.

The color of a rotting log is determined in large part by how it’s decomposing. Ultimately, fungi cause all true wood decay, and most wood-rotting fungi fall into one of two camps based on how they break wood down: they cause white rot or brown rot.

The difference between white and brown rot is based on the polymers being consumed. On average, dry wood is 50% cellulose (a polymer formed from chains of the sugar glucose), 25% hemicellulose (a collection of simpler polymers with branching chains of mixed sugars), and 25% lignin (a group of complex and strong polymers that help give wood its rigidity). In pure form, cellulose and hemicellulose are white, while lignin comes in shades of brown.

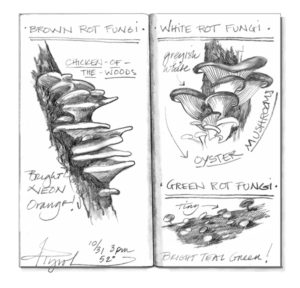

Brown rot fungi consume the cellulose and hemicellulose, snipping those molecules down to their component sugars, which the fungi then absorb. Brown lignin is left behind, and the decayed wood tends to crack into cubes, which eventually crumble into fine particles that are an important water-retaining component of forest soils. Brown rot fungi include one of my favorite mushrooms: the neon orange chicken-of-the-woods.

White rot fungi digest all wood components, but as they do, brown lignin is bleached, leaving the wood looking very light. There are different categories, including “stringy white rot” or “spongy white rot,” but all types tend towards a fibrous texture because a portion of the cellulose remains until the end. Oyster mushrooms are a delicious example of white rot fungi.

Brown rot and white rot can be recognized by their colors most of the time, although white rot is often yellow or beige, rather than pure white. As with many aspects of forest life, however, there are exceptions. Some white rot fungi are known to cause a red-brown-colored decay in conifers. And wood that was originally decayed by true wood rot fungi can be colonized later by other kinds of fungi that are looking for leftovers. This rotten wood darkens, even if it was originally decomposed by a white rot fungus.

The spectrum of decayed wood includes some colors that aren’t directly related to decomposition, but are also caused by fungi. I frequently see fragments of striking, teal-colored wood on the forest floor, which indicates the presence of blue-green cup fungi (Chlorociboria aeruginascens or C. aeruginosa). Most commonly these fungi are seen as “green rot” or “green stain” on decaying hardwoods. If I’m paying close attention throughout the fall to rotten logs, I can find their fruiting bodies: tiny cups or discs the same brilliant teal as the stained wood.

The green stain caused by blue-green cup fungi is not a case of true wood decay. The fungi live in the dead wood, but don’t actively break down its components the way white and brown rot fungi do. Italian craftsmen in the 14th and 15th centuries used green stain wood for inlays, and modern-day woodworkers also sometimes use this wood.

Other cases of fungal wood stain are used for aesthetic effect, too. Blue stain, especially in pine, is used in architecture and woodwork. The stain is caused by the presence of brown fungal hyphae in the wood; an interaction with the wood gives an overall blue-gray appearance.

The earthy rainbow of decayed and fungal stained wood reveals how fungi contribute to the richness of forests. With their own subtle beauty, each color shows that the fungi are busily recycling old wood, returning nutrients to the living forest.

Rachel Sargent Mirus lives in Duxbury, Vermont. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: www.nhcf.org.