By Catherine Schmitt

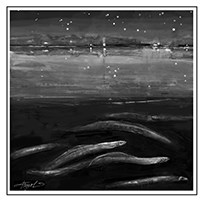

Fall’s cooling temperatures signal many changes. Among the least visible, but most incredible, is the migration of the American eel.

Somewhere right now, at the bottom of a lake, pond, or river, an American eel is preparing to leave the home she has known for three, 13, or maybe even 30 years. Her yellowish skin has turned to silver, her eyes and nostrils expanded to take in more sights and smells, her body becomes strong with muscle and fat. She is ready to go.

A few hours after sunset, she will begin the journey of more than 1,000 miles, down rain-swollen rivers to the ocean. She will travel against the currents, returning to the warm and grassy oceanic gyre known as the Sargasso Sea. There, among millions of her kind, she will mate, release millions of eggs, and die.

Scientists have yet to document the phenomenon of American eel spawning, which takes place somewhere in or around the Sargasso Sea. Exactly where remains one of the great mysteries of the world. Researchers have tried tagging eels, tracking larvae, searching the sea with nets — all without success. What they do know is that larval eels float near the ocean’s surface, somewhere between Bermuda and the Azores, and are carried off by currents including the Gulf Stream.

More than a year after the silver eel leaves her home on an autumn night, her young will go through a metamorphosis, from drifting larvae to tiny “glass” eels with the ability to swim. As they approach the coast, perhaps sensing land — some scent of the forest beyond — they head upstream, changing now as they grow into “yellow” eels. Some will stay in bays and estuaries while others continue on, riding the high tides on the darkest nights, swimming up rivers through the spring and summer to distant lakes, ponds, and reservoirs.

American eels are thought to occupy the broadest array of habitats of any fish in the world. They range throughout the Atlantic, Gulf, and Caribbean coasts, from Labrador to Venezuela. Historically, the species lived throughout all of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and most of New York, including Lake Ontario, but Niagara Falls blocked them from reaching Lake Erie and the upper Great Lakes. They live in water salt and fresh, fast and still, warm and cold. Unlike salmon and other sea-run fish, they have no fidelity to the particular habitat their parent came from. The eels that travel the farthest tend to be female.

During the day they burrow in mud, wallow in sand, hide amid aquatic plants, and tuck behind boulders and fallen trees to avoid predation from eagles, osprey, loons, and otters. They wait for night to eat, feeding on a wide variety of worms, insects, clams, crayfish, frogs, and fish.

Eels are also food for humans. A 5,000-year-old eel weir on the Sebasticook River in Maine suggests a long history of fishing in the region, and eels remain important to Wabanaki people today. Eel recipes can be found in 19th-and 20th-century New England cookbooks. Today, in some places, yellow eels are fished with baited pots and (usually accidentally) caught by anglers. In Maine rivers there is a net fishery for young glass eels and elvers, which are shipped to Asia and grown in aquaculture ponds, later to be sold as kabayaki and unagi.

While eels continue to live throughout most of their historic range, they have declined in abundance. Their habitat has been destroyed and polluted, the ocean currents they rely upon are shifting due to warming temperatures, and dams block their migration. Turbines at hydroelectric dams are particularly lethal to eels traveling downstream.

Fishing pressure, lack of safe passage at dams, and reduced abundance in much of the eel’s range led to petitions to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to consider legal protections for the American eel. In both 2007 and 2015, the agency found that Endangered Species Act listing was not warranted, although since then, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission determined that the American eel population remains depleted, with continued downward trends “a cause for concern.” The International Union for Conservation of Nature includes American eel on the “Red List” of endangered species.

American eels are less common than they once were, but they remain widespread. Of the many gifts exchanged between northeastern forests and the sea, the eel is worthy of attention, especially now, as they slip downstream, silver in the dark of autumn night.

Catherine Schmitt is a science writer and author of “The President’s Salmon: Restoring the King of Fish and its Home Waters.” The illustration for this column is by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.