By Rachel Sargent

I put the small brown ant I had mounted (but never identified) under a microscope and peered down at it. Two huge, headlight-like eyes stared back at me. That couldn’t be right; ants don’t have eyes that size and shape. I took the specimen to my professor, who initially waved me off with, “It’s an ant.” But after looking at it under magnification he excitedly turned to a guidebook showing several unique species of jumping spider that look uncannily like ants.

Ant mimicry is a popular defense against being eaten amongst arthropods, including many spiders. Ants aggressively defend themselves with a strong bite, sting venom, and can call in dozens of nestmates as reinforcements. Spiders, on the other hand, have no chemical defenses and are loners. They are particularly vulnerable to being eaten by larger spiders, wasps, and birds — predators which prefer to avoid ants. So, if a clever spider can mimic an ant, it’s more likely to be left alone.

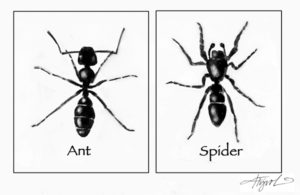

This mimicry, however, is a challenge for spiders, which have a completely different physiology and life strategy than ants. The best studied ant-mimicking spiders are in the family Salticidae: the jumping spiders. Jumping spiders are compact, have two body segments and eight legs, and have excellent vision characterized by two large, round, forward-facing eyes — like the ones I saw under the microscope. They are wandering hunters who stalk and ambush insects and other spiders by leaping at them from a distance, like a cat going after a mouse. By contrast, ants are skinny, have three body segments with six legs, and use chemical cues from their antennae to find food.

Spiders that mimic ants have special physical adaptations that make them look very ant-like. These spiders have elongated bodies and often match the coloration of a particular ant species. They may have a false “waist” in their abdomens to create the appearance of a third body segment. Some have dark patches on the sides of their head that look like ant eyes.

A good mimic must move and behave like an ant, too. The ant-mimicking jumping spider Myrmarachne formicaria, found throughout North America, walks in a winding path, just like an ant following a chemical trail. They pause frequently to briefly raise their forelegs into an antennae-like posture. Their behavior is fast enough to fool animals with slower visual systems, including humans, into thinking they are watching an ant at work.

A mimic could look and move like an ant, however, but still smell like a spider, allowing non-visual predators to identify it. Wasps, for instance, use vision to target potential prey from a distance, but once they’ve pounced, they only sting if the chemicals from the target’s cuticle smell right to their antennae. Many ants will also happily eat spiders, creating a dangerous situation for the ant-mimicking arachnids who must live in the same areas as the ants they are copying. Like wasps, ants rely on chemical cues more than vision when hunting.

Some ant-mimicking spiders have a defense against this, too. While they don’t appear to copy ant body odors, ant-mimicking spiders’ own signature smells are reduced, so they don’t smell like spiders either. For example, another widespread North American ant-mimicking jumping spider, Peckhamia picata, seems to have smell invisibility. When wasps have the option of P. picata or some other, non-mimic jumping spider as prey, they will investigate both with their antennae, but only sting and fly away with the non-mimics.

There’s one more challenge ant-mimicking spiders face: potential mates must avoid mistaking each other for ants. Little research has been done on ant-mimicking spiders and courtship, but early observations from a group at the University of Cincinnati provide tantalizing evidence that the spiders retain strategies for spotting each other. A predator’s-eye-view of a spider is likely to be from the top. In the jumping spider Synemosyna formica, juveniles mimic small acrobat ants (Crematogaster spp.) and have an ant-like shape from the top and side views, while adults look like a slightly larger carpenter ant (Camponotus spp.) from the top but retain their spider shape from the side. Many jumping spiders are famous for their elaborate mating dances, so perhaps S. formica shows off its spiderly side profile during courtship.

As I found out firsthand, ant-mimicking jumping spiders are masters of disguise. When you see ants running around, look closely — it’s possible some of those ants are really spiders.

Rachel Sargent Mirus lives in Duxbury, Vermont. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.