By Rachel Sargent Mirus

Last summer while working in the garden, I was startled when a fast-flying wasp dropped a plump pumpkin spider on the soil in front of me. The wasp landed, grabbed the spider, and wiggled backwards into a small hole I hadn’t noticed, quickly covering the entrance as if to say, “Nothing to see here.” It was the first time I’d seen a digger wasp provisioning an underground nest.

I learned about digger wasps in an introductory biology class. Niko Tinbergen, a Nobel Prize-winning Dutch biologist who helped develop the modern study of animal behavior through the mid-20th Century, tested mother digger wasps’ instinctive navigation abilities. The wasp mothers he observed kept up to five nests, returning regularly to check on their larvae. They used patterns of landmarks to re-find their nest entrances but paid no attention to the exact nature of the landmark; so, if a nest had a circle of stones around it, the mother wasp would check for it within any nearby circular arrangement of similarly sized objects.

Reading about Tinbergen’s findings many decades later, I was amazed he was able to so closely observe the learning behaviors of a flying insect. But it turns out digger wasps are easy to spot. For example, one of the most common members of this family in the Northeast is the great golden digger wasp (Sphex ichneumoneus), which is about an inch long and has a bright rusty-orange body.

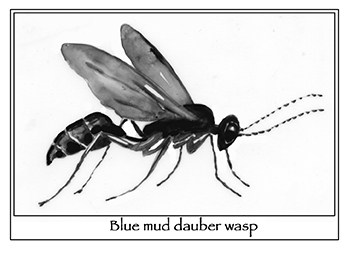

Digger wasps come in different colors and sizes, but all have a very skinny, ant-like waist called a pedicel connecting their thorax and abdomen. They’re closely related to bees. While bees are hairy and stout, however, digger wasps are smooth and slender. Digger wasps are also solitary. Many species of digger wasps burrow in sandy, well-drained and sparsely vegetated soil. Others, including the organ pipe mud dauber (Trypoxylon politum), build tubular nests out of mud, which are commonly found on man-made structures.

After digging or building each nest cavity, the mother wasp fills it with paralyzed prey, then lays a lone egg and moves onto creating and filling the next chamber. Different kinds of wasps provide different kinds of insects or spiders for their offspring, but all of them leave the prey alive and paralyzed. This way, the food stays fresh for when hungry larvae emerge from the eggs. The young wasps will pupate within their nest over the winter. In the spring they emerge as adults and begin their own cycle of mating and nest-building through June, July and Aug. As adults, digger wasps are strong pollinators, relying on flower nectar as their food source.

Many species of digger wasps are as eye-catching as the great golden digger wasp, including the beautiful metallic blue mud dauber (Chalybion californicum), another common species in the Northeast. They can sometimes be found drinking water at puddles, although I more often find them wandering around my windowsills. Often these wasps don’t build their own nests, instead “renovating” pre-existing nests by kicking out the resident larvae, laying their own eggs and restocking with new prey. Blue mud dauber nests have been found with up to 25 stunned spiders left for one lucky larva.

At up to 1 1/2 inches long, another easy-to-spot digger wasp in our region is the cicada killer (Sphecius speciosus).

These intimidatingly large wasps can catch cicadas in mid-flight and immobilize them with a sting before bringing the unfortunate insect back to their nest. These wasps are so strong that a single wasp can drag off two cicadas at once. They nest in the ground, and their entrances can be big enough to mistake for a small animal burrow.

While digger wasps can be large, like the cicada killer, and have warning coloration, like the great golden digger wasp, they are rarely aggressive toward people. In my few garden interactions with these wasps, I’d even describe them as timid; one promptly abandoned her prey spider at my feet when we had a mutually startling face to face. From a human perspective, many are beneficial because they pollinate plants as adults or sometimes hunt insects that we consider pests.

I don’t know if I’ll be lucky enough this summer to spot more digger wasps in action, but I’ll be on the lookout for these diverse and showy insects.

Rachel Sargent Mirus lives in Duxbury, Vermont. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.