By Lee Emmons

This spring, as you walk outside, keep an ear open for two distinctive bird songs: “zee zee zee zee zo zee” or “zee zee zo zo zee.” If you hear them, you’ve identified a black-throated green warbler (Setophaga virens), a bird that is often heard but rarely seen. The first song is a male attempting to communicate with the female of the species. The latter song, also sung by the male, is driven by territorial clashes. Both are regular sounds in forested areas of northern New England, especially where coniferous trees make up a large part of the mix.

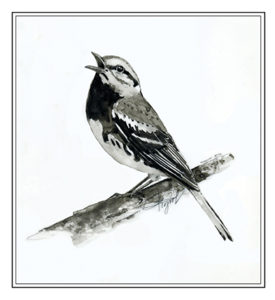

This species of warbler is among the most common in our region. Male black-throated green warblers sport an ink stain-like black throat, a vivid yellow face, and a green back. Females have a white throat but retain similar coloring on the face and back. Both sexes have large heads and a plump appearance.

Returning from a winter spent in the Caribbean, Central America, or northern South America, black-throated green warblers arrive in their summer breeding grounds in late spring. Breeding territories for black-throated green warblers stretch from New England into southern and western Canada and southern Appalachia.

Across northern New England, black-throated green warblers usually nest in hemlocks, red cedars, white pines, and spruce trees. The birds find food in the trees in which they live, taking insects — including caterpillars, aphids, gnats, and beetles — from leaves and branches. Known to hover while foraging, black-throated green warblers will also eat what they catch mid-air. While insects constitute the bulk of their diet, they will consume berries during migration.

During the breeding season, these warblers create a cup-shaped nest, situated several feet off the ground. Primarily constructed by the female, the nest comprises weeds, twigs, grass, bark, and spider silk, and is lined with feathers, hair, and moss. Black-throated green warblers have one brood per season. A clutch of three to five eggs takes 12 days to incubate. Both parents feed the nestlings, who usually leave the safety of the nest a week and a half after hatching.

Although black-throated green warbler populations have increased in recent years, they still face the threat of habitat loss.

“As an interior forest species, they require large tracts of unbroken forest to achieve greater abundance and nesting success,” said Steve Hagenbuch, a senior conservation biologist with Audubon Vermont. Consequently, any fragmentation or forest loss “leads to reduced habitat quality,” he said.

Other threats include non-native insects that impact conifers, the birds’ preferred nesting sites. A warming climate also affects these and other warbler species.

To assist in the conservation of this species, Hagenbuch recommends working to maintain large areas of intact forest. Landowners can help protect black-throated green warblers by looking into conservation easements or by allowing active harvesting that generates enough revenue to ensure that a forest remains largely unbroken. Encouraging conifers, such as hemlock and red spruce, on your land or in your sugarbush will also aid black-throated green warblers by creating or retaining nesting sites.

During the warmer months, black-throated green warblers call constantly in the woods of northern New England. One day last year, I climbed a wooded ridge in Maine and could hear the sounds of these warblers everywhere. Amidst the trees and rocky ridges, I felt like I had stumbled across their private kingdom. To my mind, these birds are the definitive sound of the northern woods this time of year.

In May, as the last of the snow vanishes and the world finally turns green, enjoy the song of the black-throated green warbler. This small bird has traveled a long way to reach the safety of our trees. I am thankful for all of the birds that have returned to our woods to sing once again.

Lee Emmons is a nature writer. He lives in Newcastle, Maine. The illustration for this column is by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.