By Rachel Sargent Mirus

On sunny, warm days, houseflies hatch and buzz around homes and offices. These flies complete aerobatic stunts that easily evade human efforts at swatting or shooing. That aerial agility, so frustrating to the would-be swatters, is thanks to a pair of highly specialized sense organs called halteres.

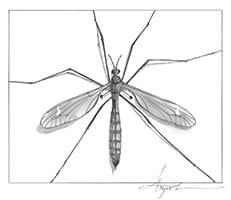

Halteres are modified wings loaded with sensory cells and are known to occur in only two insect orders: the Diptera and the Strepsiptera. The Strepsiptera are a small and unusual group of wasp parasites with males that have front wing halteres. The Diptera, or “true flies,” are diverse and include houseflies, mosquitoes, craneflies, and gnats. The halteres of these true flies are modified hindwings. While these tiny organs don’t contribute to the aerodynamic forces used for flying, Diptera halteres allow flies to spin, dip, and zigzag in flight.

Haltere means “little barbell” and refers to their ball-on-a-stick shape. Michael Dickinson, a professor at Caltech and fly flight researcher, describes halteres as having a lollipop-like shape. Despite their simple appearance, however, Dickinson noted that, “like most insect organs, halteres look more and more complicated the more you study them.”

If we consider only the motion of the halteres, their behavior does seem simple and is clearly related to wing motion. A fly in flight beats its forewings — which are responsible for lift and propulsion — up and down. At the same time, the halteres beat up and down, but in the opposite direction; as the wings go up, the halteres go down. The oddity of a flight organ with little aerodynamic purpose has attracted human curiosity for a long time.

Recorded observations of fly halteres date back to the early 1700s, when English scientist William Derham concluded that they contribute to a fly’s sense of balance during flight. Research in the early 1900s discovered two key sensory roles of halteres: detecting body rotation using inertial forces, and acting as a master clock for wing beat timing. To put it another way, halteres are a fly’s gyroscope and metronome all in one tiny, lollipop-shaped package.

Halteres act like built-in gyroscopes because, as a fly in flight beats its halteres at the same rate as its wings, those oscillations of the halteres create inertial forces. If the fly pulls a loop-the-loop, the halteres resist the changes in direction, causing them to bend slightly. The fly can detect that small bending and interpret it as body rotation. Using this understanding of its body position, the fly can activate reflexes to correct a tumble or make choices about its flight path.

As Dickinson’s research has helped to show, since the halteres are beating in time with the wings, the halteres can act as an independent and precise timer, just like a metronome. And timing is everything in fly flight. One of the rules of insect aerodynamics is that smaller size requires faster flapping. Many flies are small even by insect standards, so they must flap their wings very, very fast — for some species, up to 600 beats per second.

To avoid tiny timing errors that might be disastrous at flight speeds, flies also need fast visual responses. The halteres transmit information about body position and wing beat timing to other parts of the fly’s nervous system, allowing flies to maintain steady vision, even during rapid and complicated flight maneuvers. The neural link between a fly’s halteres and eyes results in an integrated vision, balance, and timing sensory system that not only allows flies to fly, but to fly with amazing agility.

Dickinson emphasizes that flies are operating at speeds that are difficult for a human to imagine. Their visual system processes 10 times faster than ours, while their muscles are firing at hundreds of beats per second. To a fly, our human world must appear to operate in slow motion, just as we perceive their aerial maneuvers as mind-bogglingly speedy.

Rachel Sargent Mirus lives in Duxbury, Vermont. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.