By Rachael Mirrus

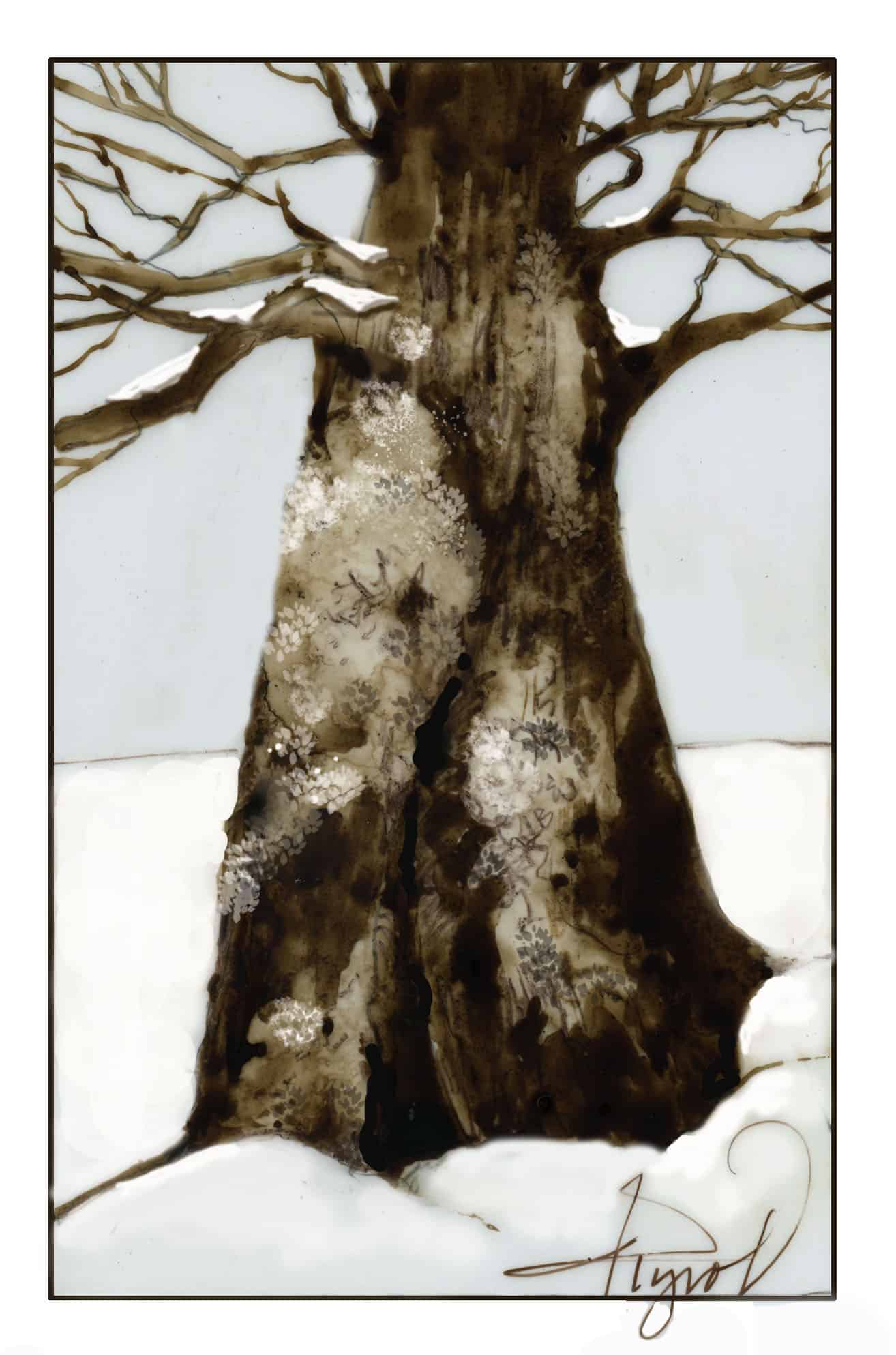

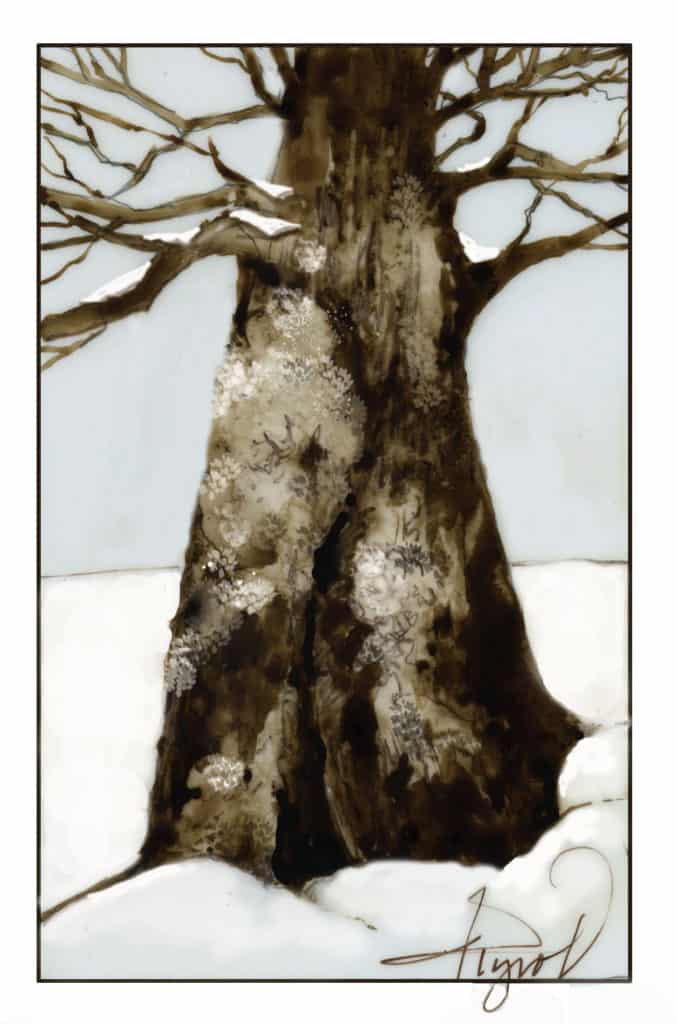

In a February forest, evergreens provide welcome color. But look more closely on the bark of trees, both conifers and hardwoods, and you’ll find other bright hues, from sunny yellows to blue-greens. These are lichens, common but often overlooked members of the winter woods.

Lichens have varied and intricate growth patterns, but with their small stature, they can be easy to miss. While they often seem plant-like, they are actually a symbiosis between fungi and one or two other kinds of organisms, algae and cyanobacteria. They are tough customers, surviving in habitats that thwart many other organisms, including the arid and exposed surfaces of rocks.

Like plants, photosynthesis in lichens is limited by cold temperatures and dry conditions. Water freezing within their tissues can also cause cellular damage. Yet lichens are well adapted to survive the cold and served as the advance guard in recolonizing the landscape after the last Ice Age. When dry winter air causes them to dehydrate, lichens go dormant, just as they do during dry summers. Some lichens can return to photosynthesizing when the humidity rises above 60 percent, even at subzero temperatures. Some winter-hard specimens can get enough humidity for photosynthesis by harvesting moisture from snow sublimation.

One of the reasons lichens can thrive in winter is that they’re skilled organic chemists, producing many compounds to make their harsh environments livable. Some have antifreeze proteins in their tissues. Some also produce surface proteins that kickstart ice crystal growth, producing an insulating layer of ice. As that external ice freezes, it releases a small amount of heat energy, ever so slightly warming the lichen.

In common with mosses, lichens are poikilohydric, meaning they have no way to prevent water loss in dry conditions, and can fully desiccate, continuing to exist in a form of suspended animation. Winter desiccation has its advantages: there are fewer free radicals around to damage lichen DNA, and ice crystals are less likely to form and shred their tissues. Some lichens have recovered after 10 years in this state, while others have revived after a dip in negative 320-degree liquid nitrogen.

Lichens’ restorative superpower – resuming photosynthesis after surviving extremely cold and dry wintry conditions – has inspired lichen space “walks.” In a 2015 study, scientists attached lichens to trays that were placed outside the International Space Station for 18 months. Here, the lichens experienced temperatures ranging from negative 7 degrees F to 109 degrees F, unfiltered ultraviolet radiation, and desiccation. Seventy-one percent of these lichens re-started normal growth after returning to Earth-like conditions.

One of the lichen species privileged to take a space trip was Xanthoria elegans, a beautiful yellow-orange lichen that can be found around the Northeast encrusting rocks, especially in coastal areas. If you spot it, say hi to this lichen astronaut!

Cold, dry winter conditions have prompted many clever adaptations that allow organisms to survive and even thrive. In their own quiet way, lichens are some of the most successful of all the winter survivors. On your next winter walk, don’t forget to look beyond the plants and their special winter adaptations to the humble lichens, many of them photosynthesizing against the odds, even in winter.

Rachel Mirus lives and writes in Duxbury, Vermont. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.