By Michael J. Caduto

Last June, my wife Marie and I encountered a mature wood turtle while walking through a forest near our home. We admired the intricate topography of its shell, inspiration for this species’ scientific name: Glyptemys (“carved turtle”) insculpta (“sculpted”). The 9-inch adult had brownish-black skin and scarlet-orange patches on its neck and legs. Its lower shell was a rich yellow encircled by black splotches.

Sadly, these beautiful creatures are now rare or endangered throughout much of their range, which stretches from the northeastern United States to southeastern Canada, west to the Great Lakes, and south to Virginia. Development has destroyed turtle habitat, especially in crucial riparian environments along stream banks. Poaching turtles for pets or to sell on the black market has wiped out entire populations. It is now illegal to capture, sell or possess wood turtles in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, among other states and provinces.

During summer, wood turtles wander between water and dry land, eating a variety of plants and animals, from berries and mushrooms to insects, slugs, snails, tadpoles, crayfish and small fish. They specialize in stomping the ground, prompting earthworms to surface, where they’re quickly dispatched. The turtles rarely wander much more than a quarter mile from the water.

“For the most part, they are river turtles whose entire lives are based around a home stream,” said herpetologist Jim Andrews, coordinator of the Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas.

This time of year, wood turtles have settled into a hibernaculum to wait out winter’s cold. In late autumn, wood turtles swim to a pool within a stream to seek a safe place underwater – sometimes wedged behind a log or large rock – where they’ll spend the winter. The temperature in this hibernaculum will remain just above freezing throughout the season. Turtles enter a state of brumation, during which metabolism drops by 95% and their body temperature assumes that of the environment. The turtles must be able to obtain oxygen while submerged, which they do through linings on the roof of the mouth and inside the cloaca (rear end). In April, as these streams thaw and warm, wood turtles return to foraging in fields and forests.

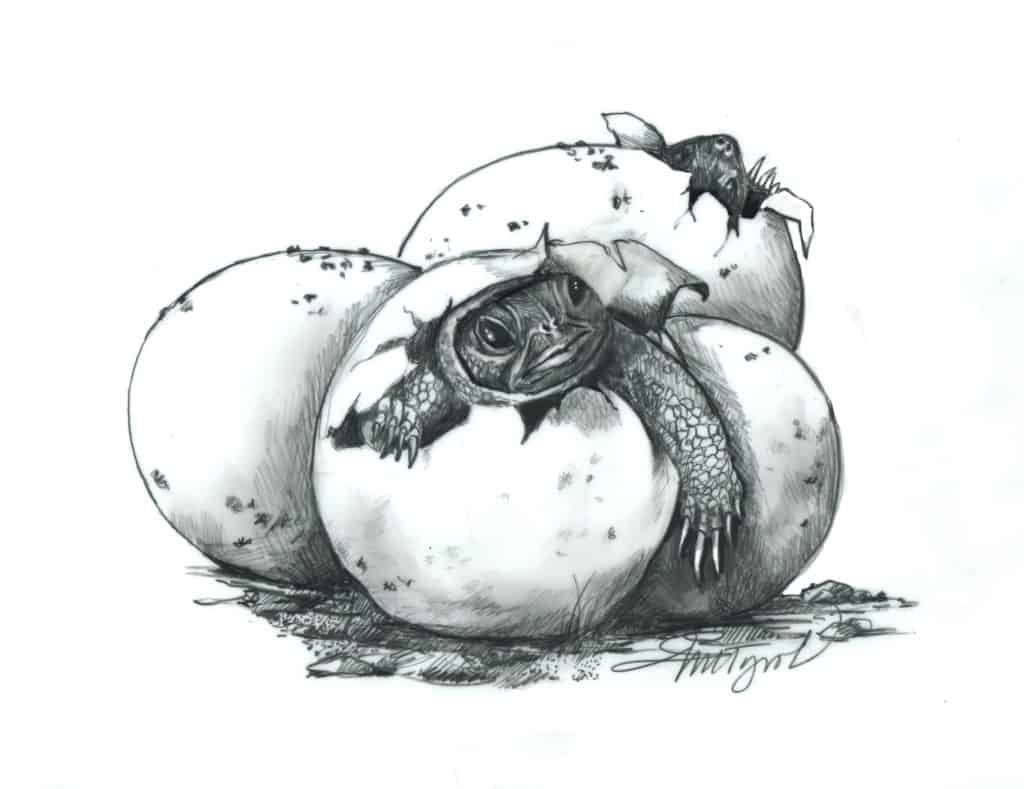

Around mid-June, the female digs a hole up to 6 inches deep on a sand or gravel bar along the edge of the river. If a waterfront nesting site is disturbed or impaired, she may nest in a sunny meadow, a field or even along a road. She lays 4-12 eggs, covers them, and tamps the ground with her lower shell. If the eggs remain safe from predators, in a little over two months, the grayish-brown hatchlings emerge and migrate to the relative safety of a stream. A female wood turtle can live for over 50 years and so produce many nests.

“The fact that wood turtles do not become sexually mature until about 14 years of age demonstrates that the long-term survival of adults is critical to the persistence of populations,” said Andrews. “There is heavy predation on eggs, so the survival of eggs and young is limited.” Everything from raccoons and skunks to foxes and coyotes will eat wood turtle eggs and young.

Other dangers include crossing roads and agricultural fields to reach nesting sites or to forage for food, as well as a decrease in suitable riparian nesting sites. Biologists and conservationists are working to protect wood turtle habitat and to educate people about this and other sensitive riparian species. Protection measures include preventing development and retaining natural vegetation along shorelines, as well as situating new roads and driveways at least 1,000 feet from aquatic environments. Waiting until late October to mow fields and meadows, and not mowing shorter than 7 inches, can also help protect turtles.

If you are lucky enough to spot a wood turtle, send a photograph to your state’s non-game wildlife experts, but keep the turtle’s location secret to discourage illegal collecting. If you find a wood turtle in a location where it is threatened, such as crossing a road – and you can move the turtle without risking harm to yourself or others – bring it to a safe place nearby (within 100 yards) and in the direction it was headed. If wood turtles are to survive, they need us to offer a helping hand, and to yield a right-of-way.

Michael J. Caduto—an author, ecologist, and storyteller who lives in Reading, Vermont—is author of “Through a Naturalist’s Eyes: Exploring the Nature of New England.” Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.