By Tami Gingrich

I can’t seem to pass a hollow tree without stopping to snoop. If there is a cavity within reach, an investigation is in order. Wear and tear around a hole, evidence of food items on the ground, or simply sounds from within tell of the tenants inside. One of my favorite tricks is to power up my camera, flash on, and poke it inside a tree cavity for a quick snap. My most memorable and rewarding discovery came while lying on my stomach at the hollow base of a huge, dead maple. Imagine my surprise when the photo revealed two downy turkey vulture chicks staring back at me! This discovery led to three years of intimate trail camera footage of the same parent pair rearing young in this giant tree.

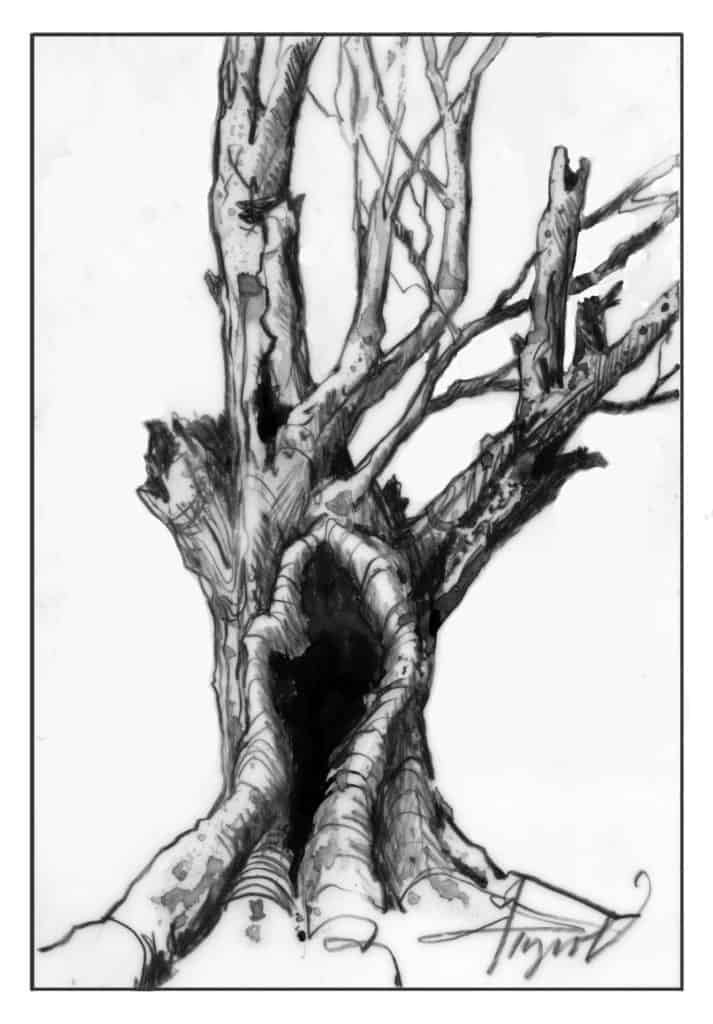

From the time a tree germinates from a tiny seed to the moment it returns to the soil to aid in the growth of yet another, it is benefitting living things. A live tree has much to offer and its advantages are many. But to say that its time is up when it dies is a sore misjudgment. The skeleton of a dead tree silently standing in the forest, littered with holes, may seem like a sorry sight to some. Yet, anytime of the year, any minute of the day, that tree may be teeming with life.

Many dead trees already have cavities that formed naturally such as hollow trunks or knotholes. These abodes are quickly snatched up by bats, barred owls, honey bees, and wood ducks. Other species create homes by excavating new holes as nesting sites. Primary cavity nesters, such as woodpeckers and nuthatches, work tirelessly to excavate cozy caverns in which to raise a family. In turn, their holes, which occupy varying heights and come in a variety of sizes, are snatched up by the plethora of secondary nesters that move in when the original inhabitants vacate.

Thus, the entire tree can be likened to that of an apartment building, with a different tenant on each floor. American kestrels, black-capped chickadees, eastern bluebirds, screech owls and great-crested flycatchers are among the birds that rely on pre-made cavities. Several species of squirrels find arboreal excavations convenient for rearing their young. The impressive black rat snake is a regular visitor to hollow trees, either waiting patiently in the shadows for unsuspecting prey to enter, or feeding on others’ eggs and youngsters it has so efficiently “sniffed” out.

By autumn, cavity nesters have completed their family duties, freeing up space for a new cast of animals to stake their claim for the winter months. Southern flying squirrels busy themselves adding layers of leaves to their nests, while raccoons snatch up the larger cavities. White-footed mice make themselves comfortable in the tiniest of holes, while groundhogs burrow beneath the decaying roots to hibernate. When a hollow tree eventually falls to the earth, its horizontal remains continue to provide shelter for reptiles, amphibians, skunks, opossums, foxes and other animals that are not adept climbers.

Black bears and coyotes also seek out larger hollow logs or trees with sizeable cavities at their base. After spending the autumn months gorging themselves in preparation for hibernation, bears may choose a tree cavity that will provide good shelter as a winter den site – and, for mother bears, the place where their cubs will be born. Coyotes, too, find larger cavities desirable for rearing their pups. At the onset of breeding season in mid-winter, they are already eyeing potential den sites and actively staking their claims through regular scent marking.

When it comes to dead trees, I suppose beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Where some see only an eyesore, I often catch my breath at the sight of the striking silhouette of an expired giant and consider the myriad animals who may call this tree home throughout the seasons. After all, the number of animals a tree benefits after it dies may be greater than what it provided when alive – which means a hollow tree might just be more alive in its death than it was in life.

Tami Gingrich is a retired naturalist and field biologist. She lives in Middlefield, Ohio. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.