By Rachel Mirus

The September before my daughter was born, my husband and I went for our last pre-baby hike around Camel’s Hump. We stopped for a snack on the ridgeline, and as we sat munching granola bars we were surprised to see a monarch butterfly flap past, battling the turbulence at this higher elevation. We watched it disappear southwards, then turned to see a second monarch, then another, fly after the first. It felt like we had stumbled on an aerial herd path as we watched half a dozen orange butterflies flutter southwards along the mountain at treetop height.

The monarchs’ daunting annual migration to winter roosts in the oyamel fir forests of Mexico is well-documented. Now, researchers have found a curious connection between monarchs’ wing color – which can range from brick red to pale yellowish-orange – and their long-distance flying success.

Andy Davis, a research scientist at the University of Georgia studying monarch migration, started his career as an ornithologist. In the world of bird research, it’s well known that an individual with brighter colors is healthier and more attractive to mates. Davis wondered if color variation could reveal anything about individual butterflies.

To quantify wing color variation, Davis chills the butterflies he’s collected to make them docile and puts them upside down on a flatbed scanner. After a butterfly is scanned and released, Davis can use a computer to precisely determine the color saturation of its wings on a spectrum from yellow-orange to red-orange. Digital quantification of wing color has allowed him to look more closely at connections between color and flight performance. For monarchs, what he has found can be summed up as “redder is better.”

While individual monarchs in every generation show a range of orange hues, the average color of each season’s generation also varies. Davis’ early research indicated that fall monarchs, who have a long flight south ahead of them, are likely to be very red. Summer monarchs, a generation that does not migrate, but spends its adult life breeding in northern regions, tend towards yellow. Based on these observations, Davis put monarchs on a sort of aerial treadmill, a “flap-mill” if you will, and found that redder individuals of any season were better flyers.

He doesn’t think the redder color is connected to aerodynamics, but rather that it’s an indicator of health. Redder butterflies, in addition to being stronger flyers, live longer, have more fat reserves, and attract more mates. Exactly how and why some butterflies are redder and stronger isn’t understood. The brick-red shades could indicate that some butterflies ate more as caterpillars, or that they are more metabolically efficient and can therefore make more pigment for their wings. As for the seasonal patterns in color variation, there might be a physiological switch triggered in the fall to ensure that the migratory generation of butterflies has the physical reserves to make their long flight. Alternatively, fall butterflies may appear to be redder on average because only the robust, red-orange individuals survive long flights to be sampled by researchers. If yellower butterflies don’t make it very far before succumbing, the fall population would quickly become enriched in redder individuals; a researcher could sample anywhere in their range after the migration had started and see the same redder-in-the-fall pattern.

Davis points out how important subtle differences between individuals can be. Monarchs may all appear to be the same orange at first glance, but a closer look has revealed that the differences in their exact wing shade tells a story about the wellbeing of each butterfly, a story that may end happily in Mexico – or not.

Monarch conservation remains an urgent mission, and the biggest survival challenge these insects face is their safe arrival in Mexico. In future conservation efforts, knowing “redder is better” could be a helpful predictive tool for the health of individual butterflies and their population as a whole. I hope for many future Septembers with my daughter watching bright orange butterflies start their epic trip south.

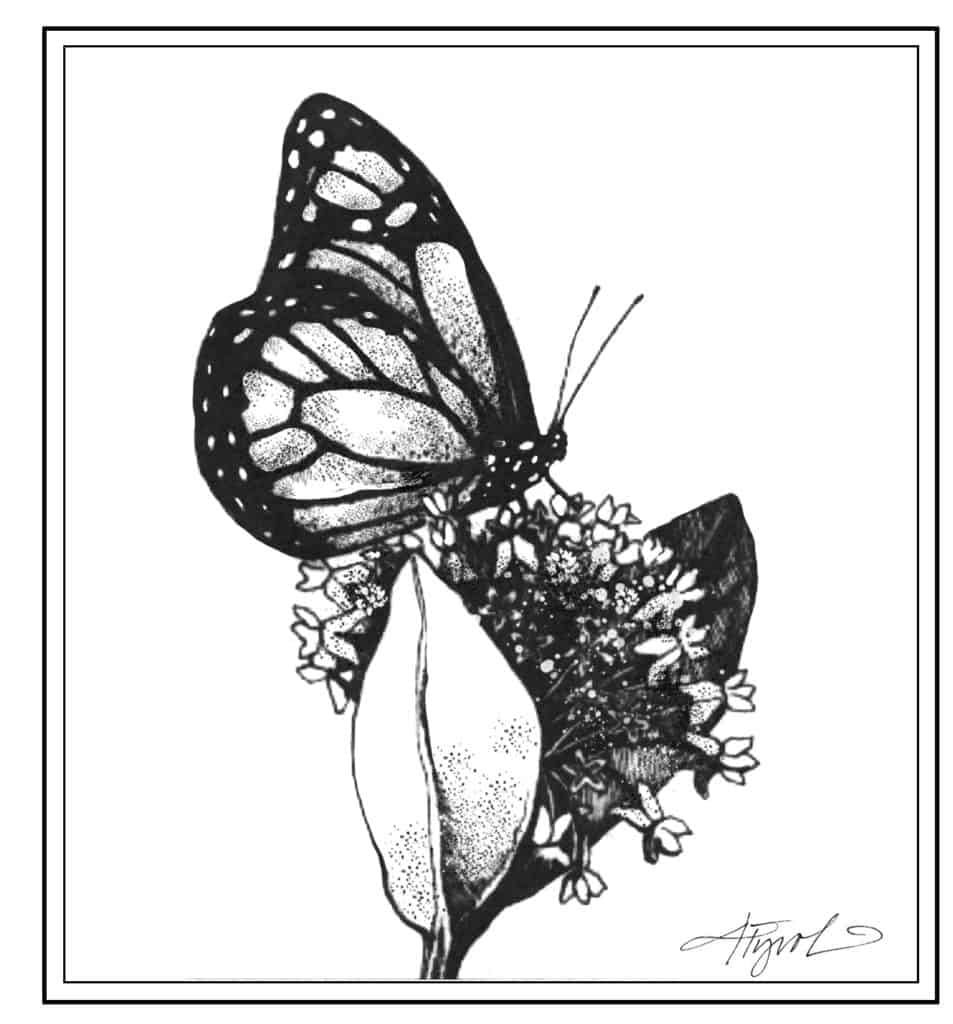

Rachel Mirus lives and writes in Duxbury, Vermont. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.