By Susan Shea

One summer day I lifted the black plastic top of our composter and jumped back, startled – a large snake was curled up on top of the compost. The yellow stripe down the center of its dark back and two yellow stripes along its sides identified it as a garter snake, our most common snake, found around rock piles, under logs, or – sometimes – even inside a house.

Color and pattern can vary among garter snakes, said herpetologist Jim Andrews, coordinator of the Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas. Some populations lack the central stripe or show only faint side stripes, and Andrews has found populations in Vermont that were all black. When anxious, garter snakes puff up their bodies with air, and a checkerboard pattern appears. The snake I saw was about 2 ½ feet long, average for an adult garter snake in our region. But they can grow larger; the longest garter snake documented by Vermont’s Atlas was 41 inches.

The snake in our composter was undoubtedly soaking up heat produced by rotting compost. Snakes and other reptiles are “cold-blooded,” or, as Andrews puts it, “solar-heated.” Because their bodies lack the ability to generate heat, garter snakes use the sun – either directly or indirectly, such as by lying beneath a tarp – to warm themselves. Snakes regulate their body temperature by moving into and out of sunny spots and shelters such as mammal burrows or stone walls. Garter snakes begin their mornings by basking to raise their body temperatures into the 80s, the optimal metabolic temperature for digestion, reproduction, and other activities.

Garter snakes are more tolerant of cold than most other snakes and range further north than any other snake – almost to the Arctic Circle in Canada’s Northwest Territories. While some snakes lay eggs, requiring a warm place for the eggs to develop, garter snakes bear live young, a key adaptation that has enabled them to live in colder climates.

One late summer day when I went downstairs to our basement to do the laundry, I almost stepped on a garter snake (and almost dropped the clothes basket). A few days later, I found several baby garter snakes in the basement. The female snake had sought a sheltered spot to give birth, and the dark, dirt-floored basement of our old farmhouse must have seemed an ideal place. She had likely mated in spring right after emerging from hibernation and had stored the male’s sperm in her body until she felt it was the right time for fertilization.

The snakelets had developed over the summer, until she contracted her body and expelled one to three at a time onto my basement floor, each coiled inside a transparent sac. The baby garter snakes soon broke through this covering. Their mother stayed with them for a few days before leaving them to fend for themselves. Large garter snakes may give birth to up to 40 young, but fortunately there were fewer than 10 in our basement, and they found their way outside.

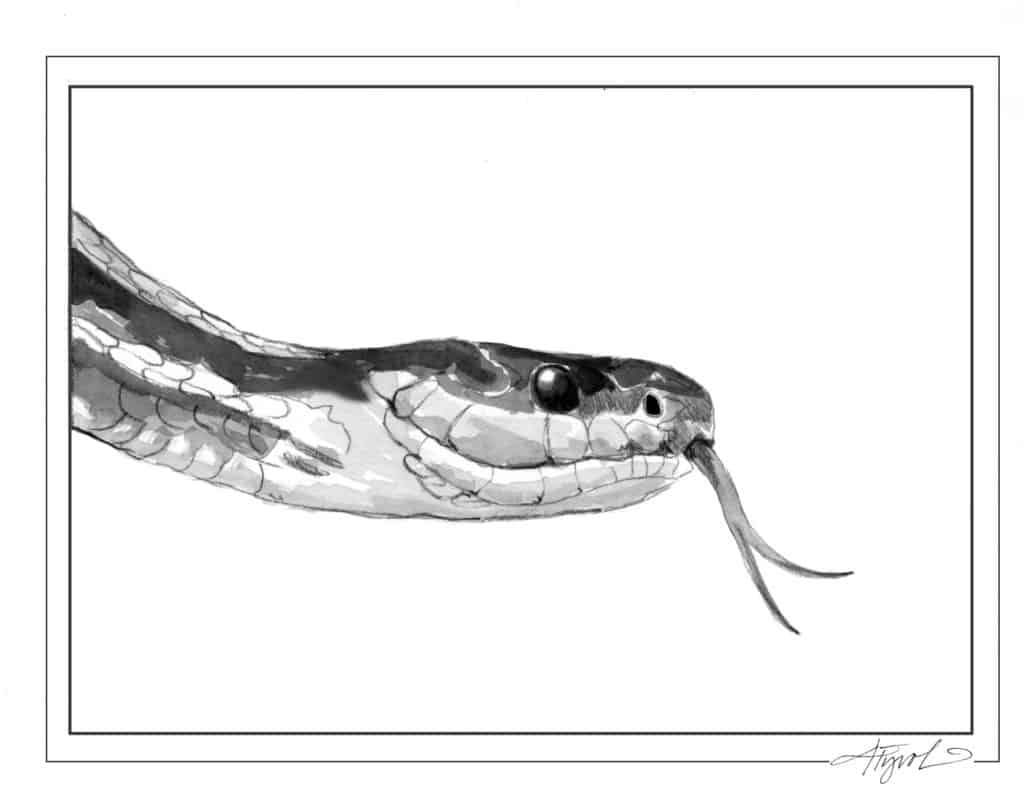

Garter snakes use their vision and excellent sense of smell to hunt for prey, which may include earthworms, insects, slugs, snails, frogs, small fish, and an occasional nestling bird or small mammal. Snakes smell with their tongues, flicking them in and out to collect odor particles, and then inserting the tongue into an organ on the roof of the mouth that interprets smells. Garter snakes grab prey with their sharp teeth to immobilize it, then slowly work it into their mouths, swallowing it whole. Because their lower jaws are only connected by ligaments and have joints in the middle, these snakes can stretch their mouths to swallow prey wider than their bodies.

In fall, garter snakes seek underground dens that maintain above-freezing temperatures to overwinter. They will den in old woodchuck and chipmunk burrows, or a crack in a house foundation, either individually or with other snakes. In areas of Canada where suitable dens are limited, garter snakes migrate miles to dens, and hundreds to thousands of snakes hibernate together. According to Andrews, northeastern garter snakes don’t need to travel far to find hibernacula, and we don’t see huge numbers of snakes wintering together here. But once he saw 20 to 30 garter snakes emerge from a Vermont den.

Garter snakes stay under cover much of the time, so don’t be surprised to see one when you’re lifting a piece of firewood, a garden tarp, or opening a garage door. They can turn up in unexpected places.

Susan Shea is a naturalist, writer, and conservationist who lives in Brookfield, Vermont. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.