By Lee Emmons

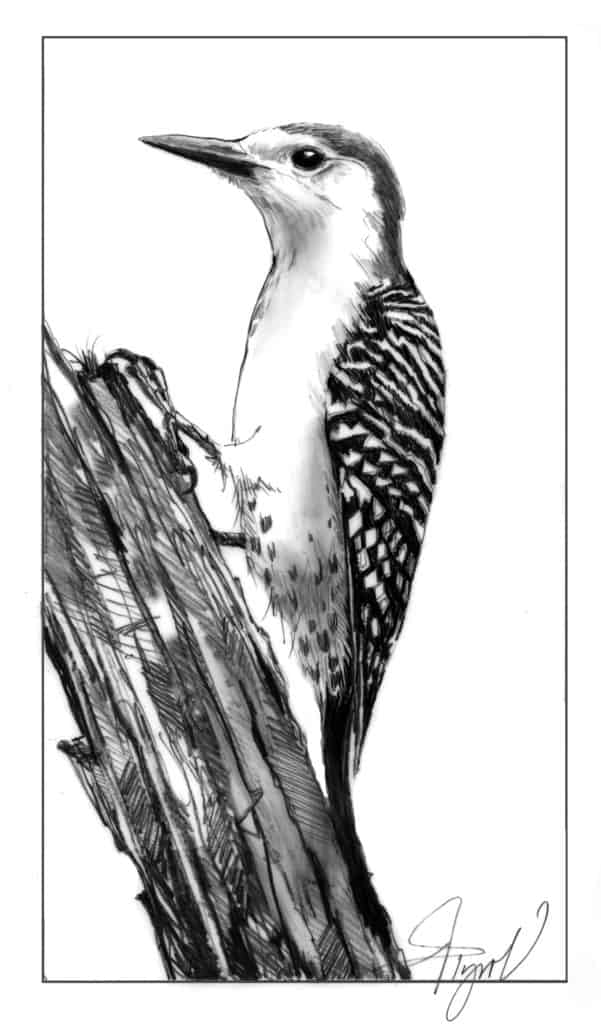

I first became acquainted with my neighborhood red-bellied woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus) when it visited my bird feeders last winter. Sporting a black-and-white-striped back with a red nape, this medium-sized woodpecker certainly made a visual impression. Its call was also memorable, a loud kwirr that sounded nothing like the other birds in my backyard. Over time, I’ve watched as it has become a regular feeder, as dependable as the black-capped chickadees and blue jays.

Originally a bird of southeastern forests and swamps, red-bellied woodpeckers are relative newcomers to northern New England. In recent years, this adaptable species has made significant inroads into the region. In Vermont, for example, they were first noted in the 1970s and are now commonly spotted in the Champlain Valley and in southern parts of the state. Birders have also noticed this woodpecker moving into parts of New Hampshire, and red-bellies now range as far north as southern Canada. Their movement has been rapid, far outpacing what range maps suggest is their northern limit.

In southern Maine, where I live, the red-bellied woodpecker has gone from a rarity to a resident breeder in a little under two decades. Seasoned birders know that the interesting-looking woodpecker with the zebra striping in their yard would have been an unusual, even improbable visitor a few short years ago. Like the northern cardinal, the red-bellied woodpecker now feels like it’s been part of the natural landscape forever, despite its short tenure in New England.

So why are red-bellied woodpeckers shifting their range to more northern realms? Ornithologist Stephen Kress has written that climate change and supplemental feeding may be assisting the bird’s northward expansion, and the Vermont Atlas of Life also suggests that backyard bird feeders may be increasing the rate of winter survival and reproductive success. Highly omnivorous, red-bellies will eat sunflower seeds, suet, peanuts, corn, sliced apples, and reportedly even sugar-water from nectar feeders.

The red-bellied woodpecker’s natural diet is also expansive and includes insects, spiders, acorns, fruits, seeds, and occasionally nestling birds. In the southern portion of its range, red-bellies will eat lizards and mangoes. Tree-based foraging is the modus operandi of the species, and they will often cache food in bark crevices.

As habitat generalists, red-bellied woodpeckers live in a whole host of locations, including deciduous forests, mixed forests, forest edges, wooded neighborhoods, and river bottoms. In my county, they live in both developed areas and deep forests. Regardless of the specific habitat utilized, red-bellies need sufficient natural cover and snags for nest sites.

Nesting occurs during the late spring and summer, roughly between May and August. Like most woodpeckers, red-bellies are cavity nesters and excavate holes in standing dead trees or dead limbs. The male uses drumming, kwirr calls, and soft taps to attract a female to his partially excavated cavity, and male and female often finish creating the nesting site together. Excavation debris provides a bed for a clutch of four to five eggs. Red-bellied woodpeckers may have up to three broods in southern areas but have just one in our neck of the woods.

Both sexes have a red nape, while the male also has a red crown and forehead. Though difficult to see from a distance, there is a light wash of red on the lower belly as well, hence the red-bellied designation. Yet, the bird’s name confuses many backyard bird watchers. Why not call it the red-headed woodpecker? Another species has claimed that name. Thankfully, the two woodpeckers are dissimilar in appearance.

I have seen many species of birds up close, but never as close as the red-bellied woodpecker. One morning, my daughter reported a sickening thud against our window. Racing outside to look, we found a woodpecker hopping around the mulch by the front steps. Dazed from a window strike, the bird froze at our approach. We watched with helplessness as the red-belly stayed immobile on the ground. Finally, just as I was about to phone a local wildlife rehabilitation center, the bird flew off into the safety of nearby trees. The same woodpecker (at least I think it’s the same one), was back at my bird feeder that afternoon.

In a time of bird declines and widespread losses in biodiversity, red-bellied woodpeckers are an exception, showing resilience by pushing forward into the northern woods, snag to snag, feeder to feeder. How will they be faring in 50 years? If my local red-belly is any indication, they’ll be doing just fine, thank you.

Lee Emmons is a nature writer, public speaker, and educator. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.