The Outside Story

By Rachel Mirus

As you swat away blackflies this summer, look closely; it may be that not all those flies are flies. Some of them might be tiny sweat bees, members of the Halictidae family, which gets its common name because some species will lick sweat from human skin.

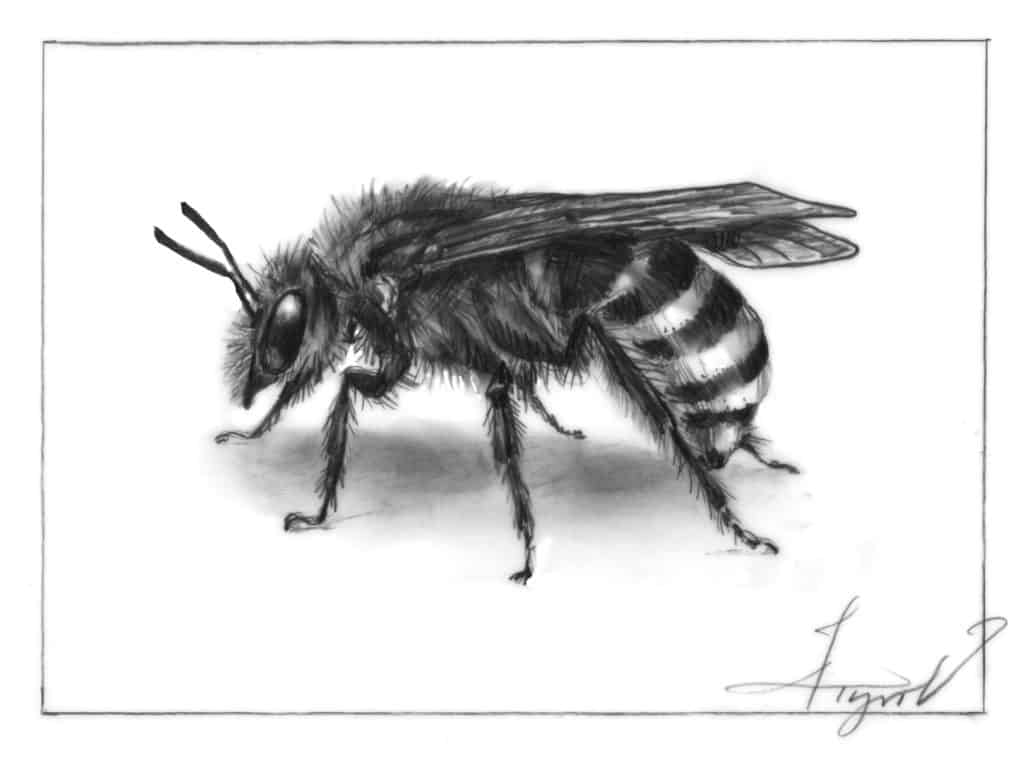

Sweat bees are a diverse group, comprising thousands of species, including at least 86 in Vermont and more than 100 in New Hampshire. They measure from 4 to 15 millimeters, about the size of a black fly, and range from dully colored to bright metallic hues. One of the most eye-catching is the bicolored striped sweat bee (Agapostemon virescens), which has a brilliantly shiny green upper body paired with a black-and-white-striped abdomen.

Sweat bees can be tough to positively identify on the fly, because the defining characteristic of the family is the shape of a particular vein in their wings, according to Spencer Hardy, the coordinator for the Vermont Center for Ecostudies’ Wild Bee Survey Project, which is recording these and other bees living in Vermont. The goal is to create a species list of all wild bees in the state, both native and non-native.

Hardy said the majority of sweat bees being found in Vermont are native species. Before the surveyors can officially count a bee, an expert must check the shape of each specimen’s wing veins under magnification.

Most sweat bees are solitary and nest in the ground, digging burrows where the soil is exposed. A few species will nest in rotten wood, either on the ground or in a standing tree. It’s entirely possible you’ve seen sweat bee nests and not noticed, as they can look very much like anthills. Hardy said the best places to look for sweat bees are sandy areas.

“Weedy vacant lots are often the most interesting,” he said, noting that unlike many animals, sweat bees prefer, and even need, disturbed areas. Since they often nest in open soil, they need areas free from plant growth. Primary sweat bee real estate can range from construction sites to eroded riverbanks, or even baseball diamonds where grass hasn’t taken hold.

Some species of sweat bees, such as blood bees, parasitize the nests of other sweat bees. Despite the fearsome name, blood bees don’t suck blood from people or bees; rather, species in this particular genus are named for their bright red abdomens. They lay their eggs in an existing nest, tricking the original nest owner into raising a blood bee brood instead of their own babies.

Yet other sweat bees are social, with individual females starting colonies and raising workers to help with subsequent broods. When they do form colonies, sweat bees are able to raise more broods in a season than a solitary bee. Some species always establish social colonies, while others will switch between solitary and social strategies based on environmental conditions. For example, nest disturbance may cause previously social bees to establish their own, new nests.

Like their honey bee and bumble bee cousins, sweat bees visit flowers and act as pollinators. Most are generalists and don’t focus on any particular blossoms, although many are fond of dandelions. A few do specialize: the pickerelweed shortface bee (Dufourea novaeangliae) only visits the purple flowers of the wetland pickerelweed, while the evening primrose sweat bee (Lasioglossum oenotherae) focuses exclusively on the blooms of evening primrose.

Whatever flowers they frequent, their small size and hidden nests make sweat bees harder to notice than buzzing bumble bees and busy honey bees. Still, their diverse life strategies make them worth watching out for. And you never know, if they like your sweat, they could be right under your nose – literally!

Rachel Mirus lives and writes in Duxbury, Vermont. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.