by Olivia Box

I love that time in spring when the hills around my house change from gray and brown to shades of yellow, green, and red. The trees have not yet leafed out, so what’s painting the forests these wonderful colors? The answer: most of our northern hardwood trees are flowering.

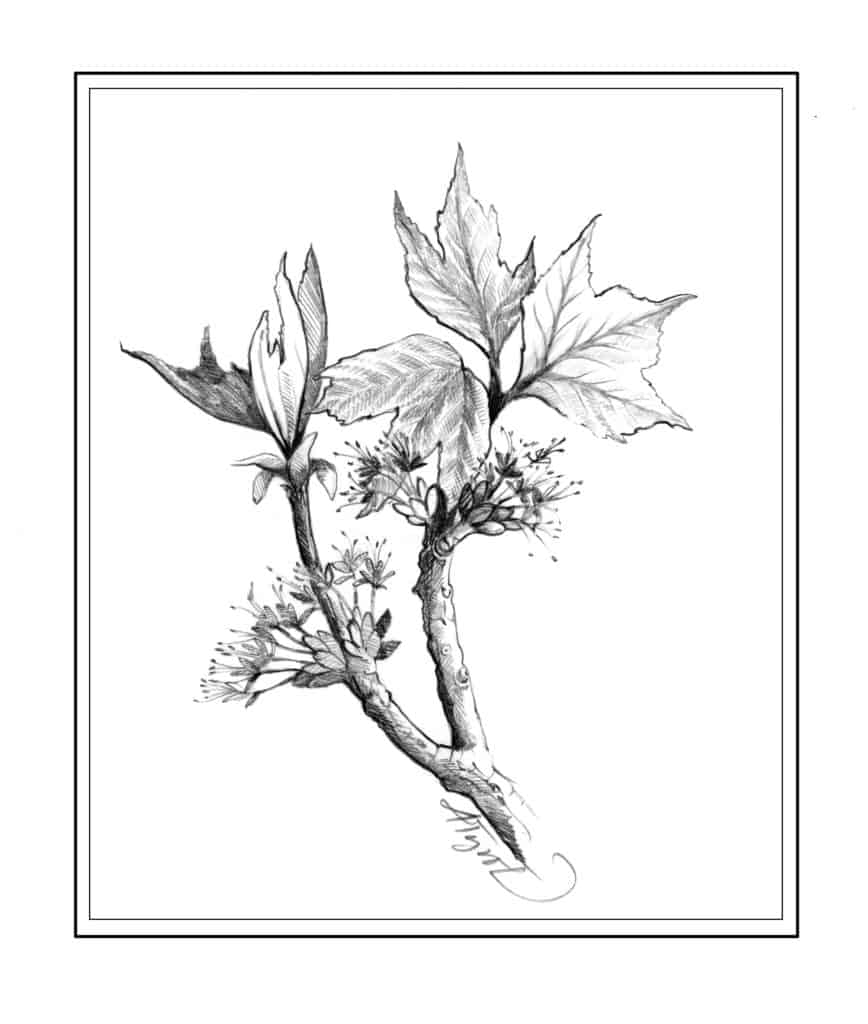

It begins with the familiar fuzzballs of pussy willows, blooming when there may still be snow on the ground. Put cuttings of these shrubby willows in a vase of water, and the soft, gray flowers will often produce yellow pollen. Red maples are another early bloomer; in wetlands where they dominate, their plentiful, swollen red buds are especially striking. These open into dainty red and yellow flowers, giving swamps a reddish hue. As spring progresses, willows and aspens follow, with long, dangling catkins composed of many tiny flowers. Then, as the weather warms, serviceberry, birch, beech, sugar maple, and other trees come into bloom, and forests erupt with color.

“One of my favorite things in spring is to look out at our beautiful hills and mountains, and easily pick out stands of different tree species from miles away,” said Aaron Marcus, assistant botanist with the Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife. “Spring is when their colors, shapes, and textures are the most distinctive at a distance. And I can look down at our river valleys and do the same for stands of floodplain forest trees.”

The function of all tree flowers is sexual reproduction. Biologist and author Bernd Heinrich, in his book “Trees in my Forest,” describes pollen blowing off male catkins “like yellow puffs of smoke.” The usually small, inconspicuous female flowers have sticky stigmas that help catch pollen. When a pollen grain lands on a female flower, it quickly grows a tube into the flower’s ovary. Sperm descend through the tube to fertilize the eggs, which will eventually develop into seeds. According to Heinrich, the female flower chemically recognizes the proper pollen, and only permits the growth of pollen tubes from the same species.

The flowers of most of our native hardwoods don’t look like garden flowers or even the blossoms of fruit or ornamental trees. Many hardwood trees, such as birches, cottonwoods, and oaks, have catkins, designed for wind pollination. These trees improve their reproductive odds by producing enormous amounts of pollen. One cluster of birch catkins, for example, may contain 10 million grains of pollen. Many of these trees flower and shed their pollen before leaf-out, an adaptation that ensures that leaves won’t interfere with the dispersal or capture of pollen.

Tree flowers come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Sugar maple flowers look like clusters of tiny hanging bells. Beeches suspend globes of flowers from long stems. In some tree species, male and female flowers are on the same tree, while others keep different sexes on separate trees. Some, like apple trees, have “perfect” flowers, with male and female parts on the same flower.

Unlike trees that use wind pollination, apples – and others, like basswood, cherry, black locust, and tulip trees – rely on insects or hummingbirds to transport pollen from male to female flower. For this reason, these trees tend to put their energy into display, rather than mass production. They produce less pollen, but package it in fragrant, showy blossoms that attract pollinators. They typically bloom later, after leaves are out, when pollinators are more abundant. Each flower’s shape, color, scent, and nectar reward are tailored to its specific pollinators. Animal-assisted pollination works well for tree species that are not as abundant and are more widely-spaced in a forest.

This spring, when trees turn red or yellow-green, get outside and take a close look at the wide variety of incredible tree flowers. Bring a hand lens to magnify the details. Connecting with nature and exploring its intricacies can provide solace in difficult times.

Susan Shea is a naturalist, writer, and conservationist who lives in Brookfield, Vermont. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.