The Outside Story

by Susan Shea

Thump. Thud. Something was hitting our window! It was a bright red cardinal flying at his reflected image in the glass – which he perceived to be an intruder in his territory. The bird kept it up for an hour, until I covered the window. On other occasions that spring, this cardinal attacked his reflection at a different window and in the car’s side mirror.

As days lengthen in spring, northern cardinals’ levels of aggressive hormones rise. Their behavior changes from winter flocking to chasing and assaulting other cardinals in an effort to establish breeding territories. The olive-gray females are also territorial and will attack their own reflections.

“Whoit, whoit, whoit.” In addition to fighting off intruders – real or imagined – cardinals maintain their territories by singing. According to ornithologist Donald Kroodsma, who has studied birdsong for decades, male cardinals have up to 10 different songs, each one repeated several times in a row. Other examples of cardinal song are often described as “what-cheer-cheer-cheer” or “purty-purty-purty.” In spring and summer, you can hear neighboring cardinals conversing with each other, sending their rich songs back and forth.

Female cardinals also sing, an unusual trait among songbirds, wrote Kroodsma in his book, “The Singing Life of Birds.” She sings less often than the male and in a softer voice, sometimes to defend territory, but mostly in a duet with her mate. The female also sings while on the nest, encouraging the male to bring her food.

Once a male cardinal establishes a territory, he courts a potential mate by strutting, bowing, and rotating to show off his handsome feathers. His red coloration comes from carotenoid pigments in the diet, and plumage brightness may be an indicator of his age and health. Researchers from Cornell University determined that female cardinals prefer redder males. Their studies in central New York showed that redder male cardinals produced more offspring in a breeding season because they obtained higher-quality territories and were paired with earlier-breeding females, and therefore had time to raise a second or third brood before fall.

After mating, the female cardinal visits possible nest sites, with the male following. The pair calls back and forth and holds nesting material in their bills. Once they have chosen a good spot, usually in a young evergreen, a dense shrub, or tangle of vines, the female builds a nest. The nest is positioned from 1-15 feet high and wedged into a fork of small branches. It is constructed of layers of twigs, leaves, bark strips, and rootlets, and lined with fine grasses, pine needles, or hair.

The female lays three to four glossy, gray or greenish speckled eggs and does most of the incubation. Predation on cardinal nests is high. Squirrels, chipmunks, crows, blue jays, and other animals will eat eggs and nestlings. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, typically less than 40 percent of nests are successful in fledging at least one young. But cardinals’ long breeding season and their strategy of raising more than one brood per year helps make up for this loss to predators.

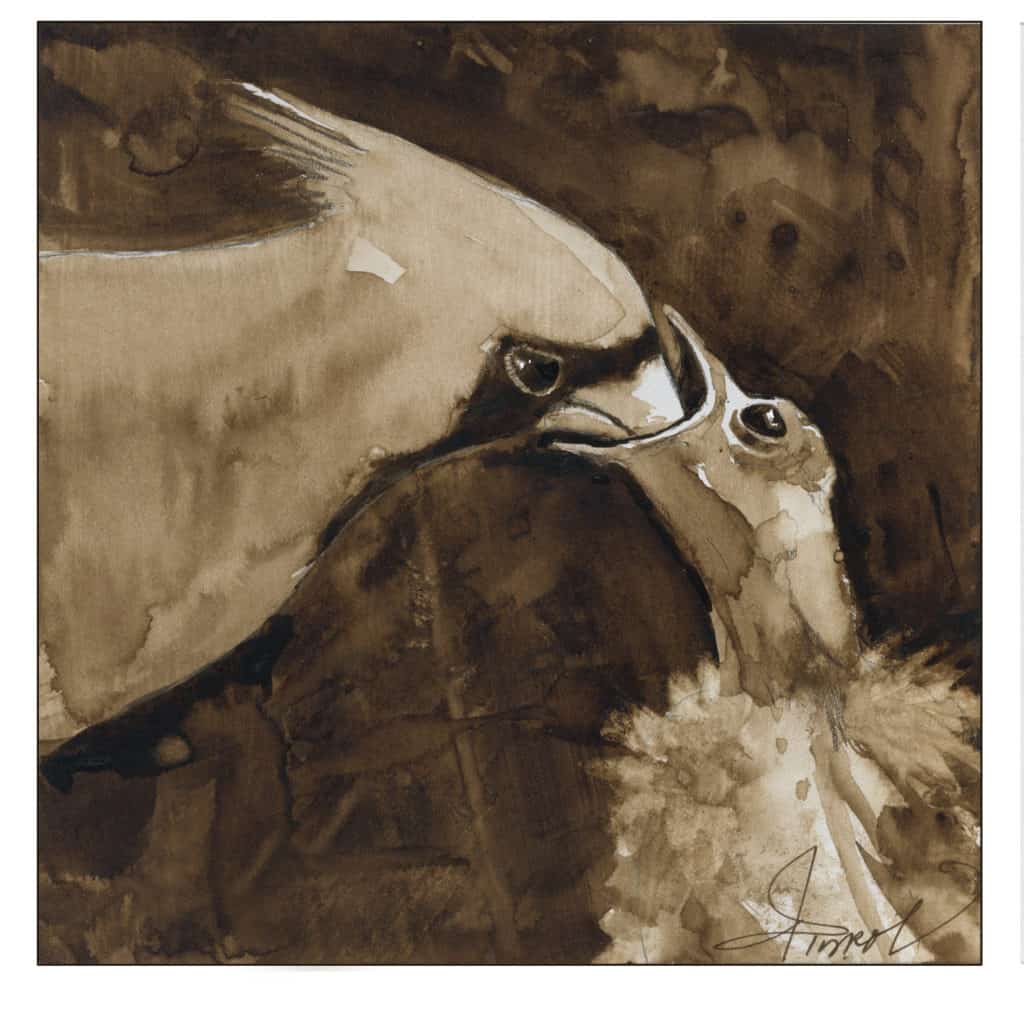

If no predator discovers the eggs, after 12 to 13 days, young cardinals hatch, eyes closed, and naked except for tufts of gray down. Their parents hunt diligently for caterpillars, beetles, and other insects to feed their nestlings, flying back and forth to the nest with food every few minutes, all day long. The young grow quickly, their feathers emerge, and after about 10 days they leave the nest. The parents continue to feed the fledglings until they learn to fly and find their own food. Sometimes the male cardinal will take care of the young while the female lays a second clutch of eggs.

Once considered a southern bird, cardinals have expanded their range northward over the past 100 years, likely due mainly to winter bird feeding. When I moved to central Vermont 30 years ago, I never saw cardinals in my area. Now they regularly visit my feeder in winter, sing and nest in my yard, and attack my windows in spring. What a joy to have this brilliant bird in the neighborhood!

Susan Shea is a naturalist, writer, and conservationist who lives in Brookfield, Vermont. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: [email protected].