By Gary Salmon

I received an interesting gift this year from California relatives, that came probably from an estate sale. It is a library book from a long defunct library by [New Hampshire author] F. Schuyler Mathews entitled “Field Book of American Trees And Shrubs.” [1915]

The givers were thoughtful enough to place my name as the last person on the library card with the prior “check out” date being November 1983.

This field guide was published in 1915 and contains beautiful water color and pen/ink drawings of most trees familiar to us today, also by the author.

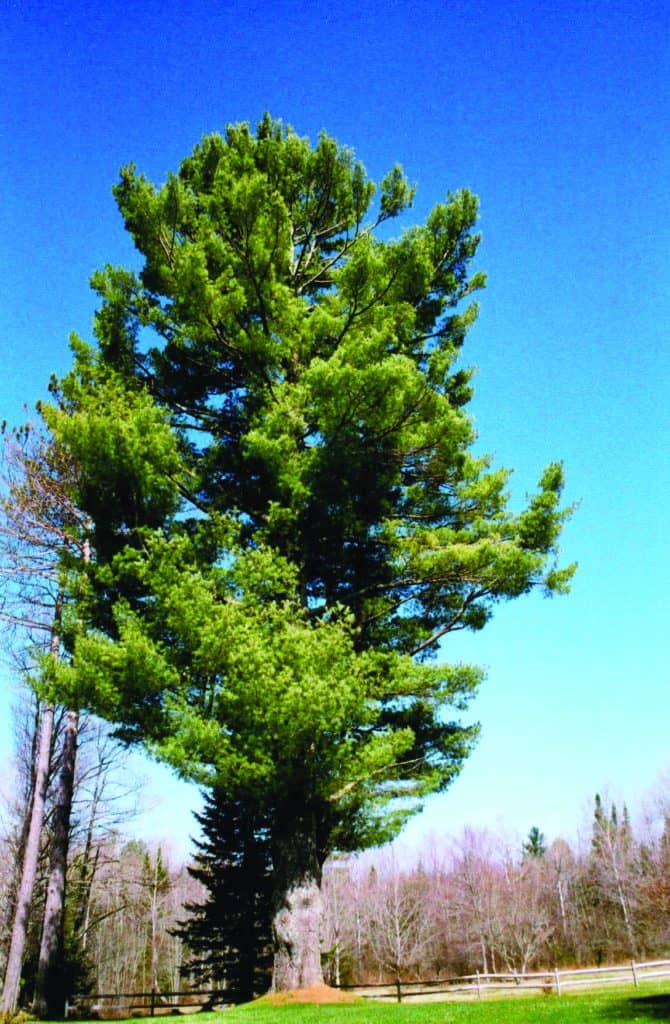

Books of this era, by default, become history books as well as they relate to forests, trees, and forest organizations. Although a field guide, Mathews’ book has comments on forests and tree threats of the time. Included in the white pine description is a paragraph regarding reckless and inexcusable waste and inordinate cutting that had depleted this resource to the point of requiring national replanting to avoid a lumber catastrophe. Noted also was that pine wood was being superseded by bald cypress, which suffered a similar over-cutting rate that nearly proved fatal to that species. Under red spruce we find that the 1911 Weeks Act creating the White Mountain National Forest was also the driving force in saving the last of the red spruce from the saw and pulp mills of New Hampshire.

Deadly tree diseases were just appearing on the horizon. Chestnut blight had just become established in New Jersey, New York City and Philadelphia. It would continue on to all but eliminate an entire tree species. Dutch Elm disease would not arrive until a few years later and, of course, this scourge of tree diseases has continued on into the present.

Even the forestry profession, capable of managing forests, was in its infancy in 1915 with very few foresters available to handle the forests and issues of the times. That left an organizational void capable of actually “managing,” and a supply of conservation organizations left to simply point out the problems and largely recommend a solution of government forest ownership.

Mathews, for example, was a member of the New England Botanical Club (NEBS) when he published this book. NEBS was housed at Harvard University, established in 1895, and still exists.

What has changed? An emerging forestry profession, only 15 years old in 1915, became a force in U.S. forest land management and policy. The ability to collect forest/tree data and analyze it (especially in the computer age) became a major force as well. And, finally, the cooperation amongst many natural resource organizations to engage in ecosystem dialogue and management further strengthened our forests and the trees within them. Lest you fall into the “all is well trap” (and who can with the forest threats today?), I was at a Society of American Foresters meeting on Valentine’s day at Vermont Tech and one of the talks was again on white pine and the half dozen threats to its health.