by Meghan McCarthy McPaul

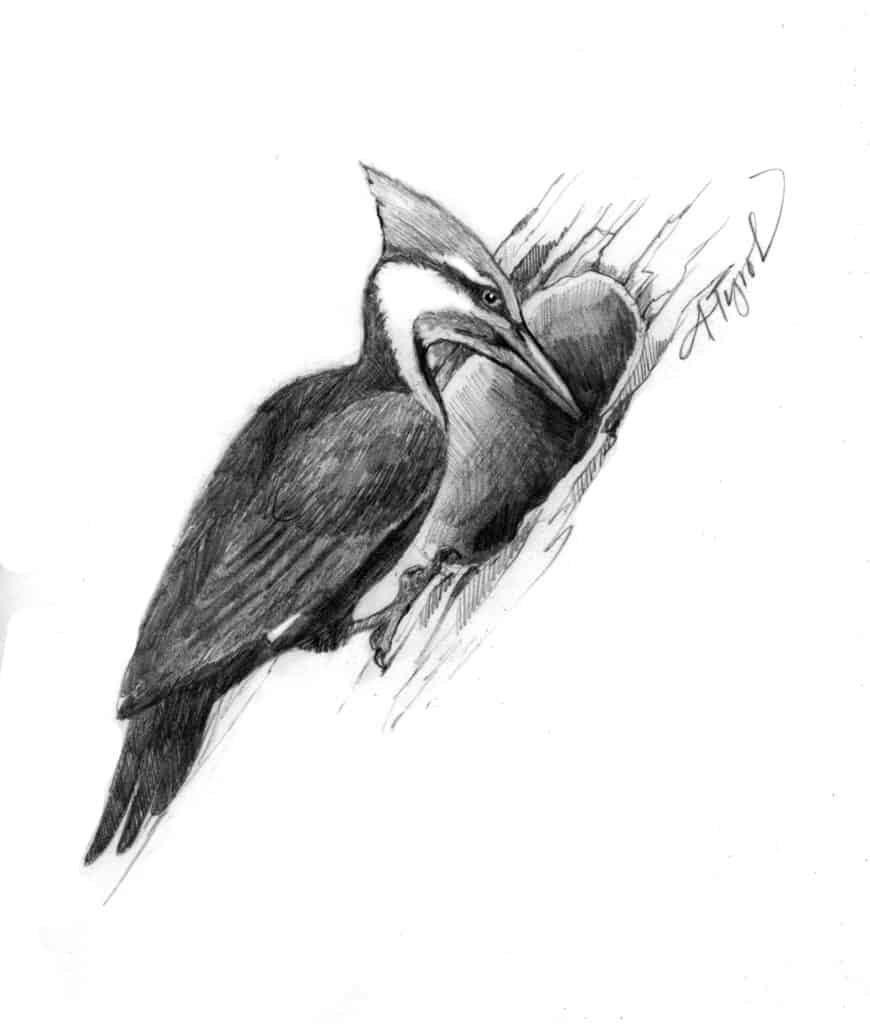

Whenever I spy a pileated woodpecker traversing the sky, I pause to watch its weird undulating flight. The jerky rise-and-drop movement of this large woodpecker is endearingly gawky – like a mini pterodactyl visiting from the Cretaceous period. This time of year, the bird’s bold crimson crest flashes in stark contrast to the mostly-muted colors of winter.

Pileated woodpeckers – Dryocopus pileatus – take their common and scientific names from the Latin word for “capped.” Both male and female sport the namesake red crest, as well as black streaks across the eyes. Measuring about 18 inches long, they have wingspans that can stretch past two feet.

These crow-sized woodpeckers live throughout the eastern half of the United States, across southern portions of Canada, and in the Pacific Northwest. They prefer mature forests with large trees, but also live in places from young forests containing snags and decaying wood to suburban areas with patches of forested land.

Wherever they call home, pileated woodpeckers stick around through the winter. On a walk through the woods, you may hear their distinctive high-pitched calls – some liken it to more of a jungle noise than something that belongs in a New England forest. More likely, though, you’ll hear the deep thudding of woodpecker beak on wood. Woodpeckers drum on trees as a means of communication, to excavate nesting and roosting sites, and – of course – to find food.

Their heavy, chisel-like bills are roughly the same length as their heads, which adds to the pterodactyl appearance, and are designed for pounding through the bark and outer layers of a tree to reach its core. Pileated woodpeckers dig out insects crawling around – or, this time of year, overwintering in larval stage. Excavations can be more than a foot long and leave piles of woodchips heaped around the tree’s trunk.

“They tend to use deciduous trees more than conifers,” said Pamela Hunt, avian conservation biologist at New Hampshire Audubon. “Most of their foraging is on dead, dying, or downed trees, but they’ll still used trees that aren’t compromised if there’s food there.”

Pileated woodpeckers’ meal of choice is carpenter ants (another common sign of their feeding: black poop at the base of trees comprised mostly of indigestible ant bits), but the birds are omnivorous, noshing on fruits and nuts when they’re in season and on an array of insects year-round. While we humans may think of insects as being primarily warm-weather creatures, these woodpeckers seek out the larvae of ants, beetles, and other bugs hidden within trees for the winter.

After excavating a hole, a pileated woodpecker will use its long, barbed tongue to reach and scrape out the buggy delicacy within. Hunt noted these woodpeckers, like all birds that weather the winter cold, spend much of their time during this season refueling on whatever food they can find. They’ll often make multiple large holes in a single snag during a feeding frenzy.

“If a tree is full of yummy larvae, the woodpecker can literally excavate the tree until there’s almost nothing left,” said Hunt.

While some of the bird species we see in winter have migrated short distances, pileated woodpeckers stick close to their nesting sites throughout the year. They are typically monogamous, and while Hunt said the woodpeckers are not necessarily “socially cohesive” during the winter, both male and female remain within their home territory.

During breeding and chick-raising season, pileated woodpeckers, like many other birds, defend their territories from interlopers. In winter, however, they often tolerate other pileated woodpeckers within their own range. The trespassers are generally young birds searching for their own territories to claim.

I will probably never be able to identify any specific chickadee from the myriad who frequent the bird feeder, or pick out one slate-colored junco from the flock hopping around the yard. But I can have some confidence that the big bird with the red-capped head and the undulating flight passing through the winter sky is the same one – or at least one of the same two – I sometimes spy in warmer months, flitting into the woods or perched on the side of a tree, pounding away.

Meghan McCarthy McPhaul is the assistant editor of Northern Woodlands magazine. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation.