Snow day! The announcement draws squeals of joy from students throughout the school district and groans from parents who must scramble to provide care for their kids and face a treacherous commute. But fourth-graders with overdue homework and harried parents aren’t the only ones whose fortunes hang in the balance when new snow blankets the region. A snowfall can bring salvation or suffering to wild critters as well.

Take the bobcat, for example. This surprisingly small carnivore stands little more than housecat-high on small paws that sink in fluffy snow. The bobcat cannot afford the energetic cost of swimming through deep powder, so its movements are limited to windswept rises, protruding rocks or logs, or trails packed down by other wildlife. When the snow piles high, long, hungry hours are spent confined to the shelter of caves or upturned stumps. A mere 6 inches of fluff can restrict bobcat movement, so it’s easy to see why they approach their distributional limit here in northern New England.

Bobcats mate in late winter, with a two-month gestation period leading to birth in early spring. The demands of motherhood during this period require that females maintain a healthy diet despite the challenges of a snowy world. Unfortunately, the bobcat’s meat-only menu features few selections, most of which gain an advantage from a fresh snowfall.

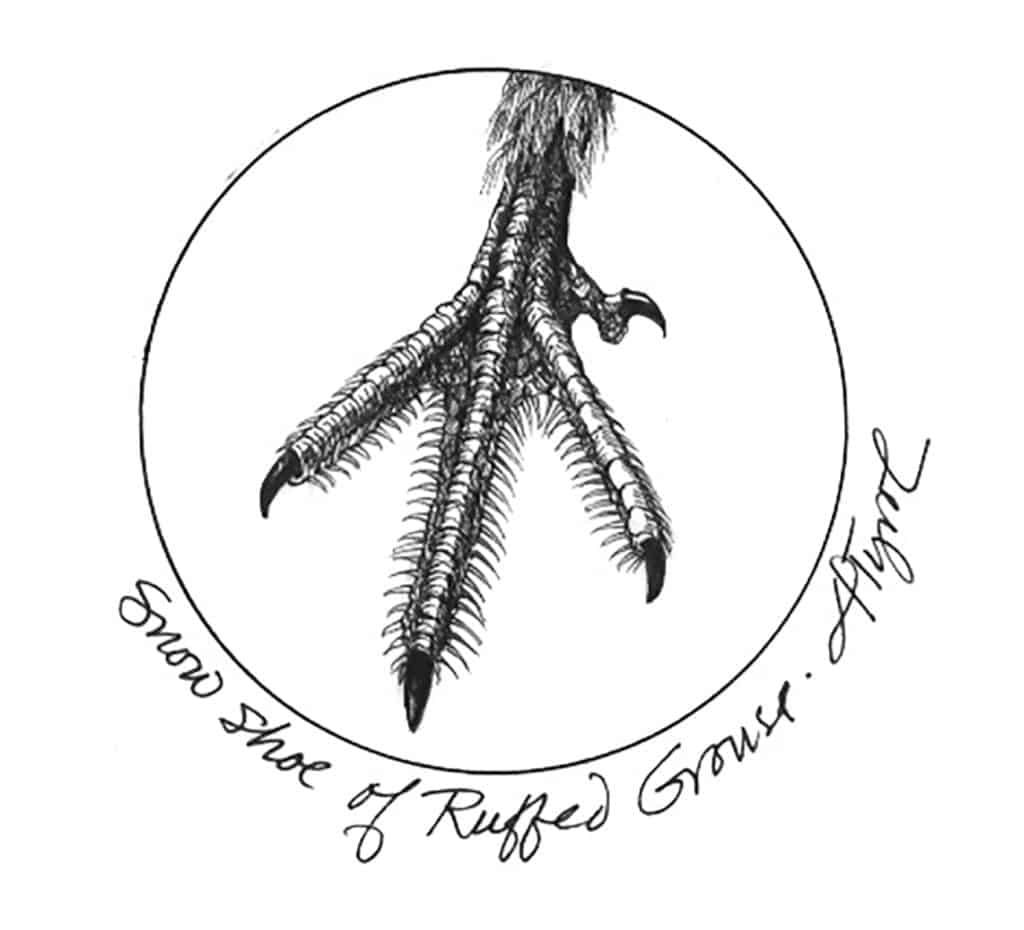

One entrée helped by a snow day is ruffed grouse, which sprout comb-like projections on their feet each fall, doubling the surface area of their feet and easing snow-top travel. When the temperature drops, they burrow beneath the insulating snow and roost in cavities that can be 50 degrees warmer than the ambient temperature on a frigid night. If the snow is soft powder, they may simply dive into their sub-nivean roosts, which provide concealment from predators as well as warmth. Upon emergence, grouse can forage on aspen, oak, and beech buds on branches higher up in the trees, thanks to the boost from the fresh snow.

Deeper snow also provides another bobcat staple, the snowshoe hare, with access to a new food supply. Hares are masters of energy conservation, occupying a small home range in winter, and hopping beyond their comfort zone only when pressed to locate new buds and twigs. New snow means new food, all without leaving the comforts of home. When not seeking food, hares hunker down in sheltered depressions beneath the snow-laden branches of conifer saplings. Outside these “forms,” snowshoe hares pack down a network of runways with their extraordinary hind feet, all the while camouflaged in their winter-white coats.

Although they lack the hare’s large feet and cryptic coloration, white-tailed deer share the hare’s affinity for shelter among conifers. While deeper snow doesn’t benefit deer, they adapt to it by yarding up in large softwood stands, tramping down their own trail network in the shadow of hemlocks, northern white cedars, red spruce, balsam fir, or white pine. Once these trees reach a sufficient height, they form canopies that intercept snow and provide refuge from chilling winds. However, a trade-off occurs when snow conditions permit bobcats to stalk a known yard for bedding deer. A stealthy tom can pounce on the back of the much larger mammal and administer a fatal bite to the back of the neck.

The smaller female bobcats are less capable of such feats and rely more heavily on small prey, such as voles and mice. Yet rodents, too, escape bobcat jaws in their tunnels. They may be safe from bobcats beneath the snow, but they face a persistent threat from weasels and remain subject to the capricious winter climate. After the storm passes and the snowpack begins to age, the tables turn again.

As snow ages, hidden cavities begin to chill, since old snow insulates only one-eighth as well as fresh snow. Sudden thaws can flood sub-nivean runways, drowning small mammals or flushing them to the surface. An ice storm can trap carbon dioxide in tunnel systems and present an air-quality hazard to voles and mice. Just as the fortunes of rodents decline, the prospects for bobcats brighten. Hardened crust enables easier access to deer immobilized in their yards, to hunting perches overlooking snowshoe runways, and to grouse unable to burrow for refuge.

The balance between predator and prey shifts as each snowstorm brings relief to some animals and deprivation to others. And while a snow day can provide a welcome change to schoolchildren, it can also tip the balance of life and death between predator and prey.

Dan Lambert is the associate director of the Center for Northern Woodlands Education. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation.