By Olivia Box

I’ve always found slender, sharp, yellow-ochre beech leaves alluring, and it’s endearing how they cling onto saplings late into the fall. However, Fagus grandifolia, the American beech, tends to get a lot of flak from foresters. The trees are plagued with beech bark disease, which ruins any timber value, and they can dominate the understory, shutting out sugar maple and prized yellow birch. Quick to arrive after most logging jobs, they sprout and sucker their way into dominance.

Beech don’t have poor relations with foresters everywhere. Across the pond, European beech is still valued, which makes sense in a continent that has largely depleted its forests. Currently, it’s heavily used across Germany and Northern Italy and thought of as a good deal for the timber industry. It’s affordable, largely healthy (though beech bark disease is there,) and in high abundance, with its range spanning central and western Europe.

Beech wood has traditionally been a low-value wood in the U.S. The conventional thinking is that red oak and sugar maple and yellow birch make high-end furniture, and beech (when it’s not riddled with lesions and full of rot) makes good firewood. But if we value trees for more than lumber, the perspective changes. As settlers moved west for greater opportunities, beech became a symbol of fertile soil, and pioneers across Ohio and Indiana set up farms alongside the range of beech. “A beech is, in almost any landscape where it appears, the finest tree to be seen” writes naturalist Donald Culross Peattie in the book “A Natural History of North American Trees.”

Even with beech bark disease, beech continues to have high value for wildlife in the Northeast, especially in the far north where it is the leading mast-producing tree. A whole suite of species – from fisher to grouse to deer mouse – depend on the nuts. In Maine, beechnut production has been correlated with the reproductive patterns of female black bears. Bears feast on beech nuts, often called “bear superfood,” as the nuts are high in fat content and have double the protein of acorns. You can see where a bear has been nut-hunting by looking for scratches on the bark, broken lower limbs, or a scramble of branches that resemble nests in the upper limbs.

Beech is a highly shade-tolerant species, and this may play to its favor as forest conditions change. However, beech bark disease will continue to stress the species. “The Climate Change Tree Atlas,” alongside vulnerability assessments, indicate mixed model results for beech. As the climate changes, it’s likely a good idea to retain and encourage healthy beech for the sake of wildlife. The definition of northern hardwood forests includes beech in the species list, after all.

“Let other trees do the work of the world,” comments Peattie after he acknowledges the commercial limitations of the beech. I have to agree. Even as diseased and dominating as beech can be, it’s hard for me to imagine a hardwood forest without it – without the experience of walking through the woods and spotting a sparse collection of silvery, muscled beech illuminated amongst the otherwise scrappy bark of birches and maples.

For so long I’ve seen the sugar maple as symbolic of New Englanders – sweet underneath but with an aged and tough exterior. However, beech also aligns with two of New England’s deepest values: hardiness and resilience.

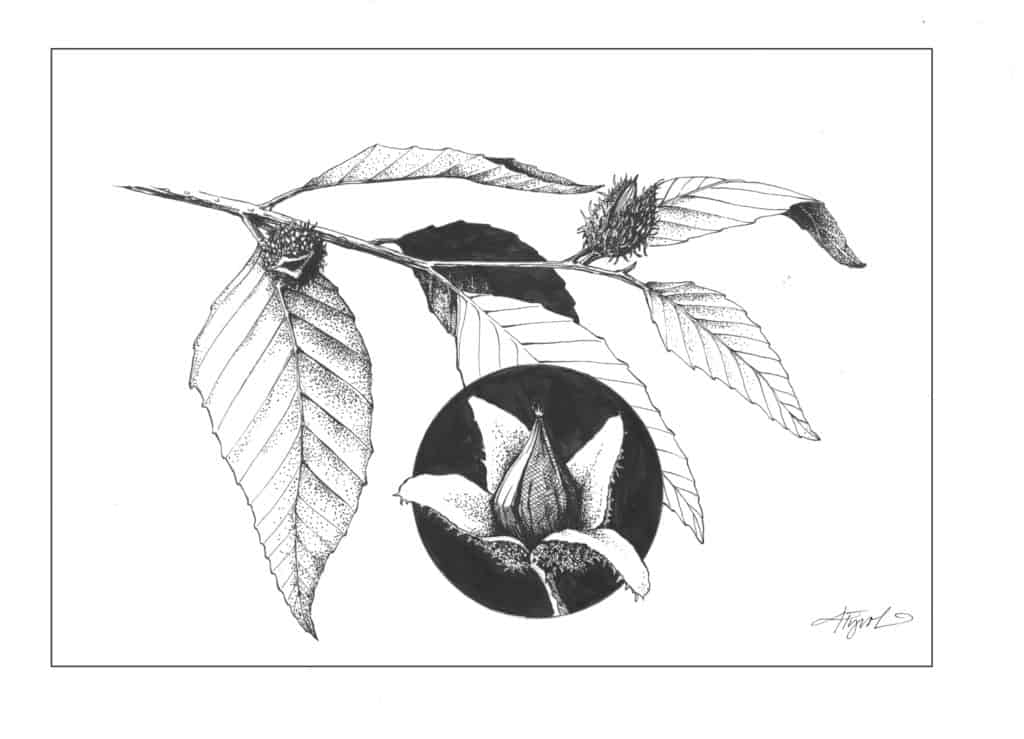

Olivia Box is a freelance writer and a graduate student at the University of Vermont, studying forests threatened by climate change and invasive pests. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation.