The Outside Story

by Susie Spikol

I fall in love easy. I’ve been mad about river otters and star-nosed moles, and of course the venomous short-tailed shrew. But my first love was a creature that is almost mythical, a shadow lingering on the edges of time. There wasn’t much of it, merely bones, teeth, scraps of hair, and an occasional breathtaking tusk. Yet Mammuthus primigenius, the woolly mammoth, was (literally) my biggest love.

It all started at the Brooks Memorial Library in Brattleboro, where a 44-inch tusk was on display when I was a kid. Found in 1865 in a nearby bog, this tusk was my first introduction to this elephant-relative that roamed the hills and valleys of New England more than 12,000 years ago. In my adult rambles along the soft yielding edges of wetlands and paddles down remote rivers, I’m always searching for a tooth, a bone shard, or the treasure of a tusk. That is what mammoth love gives me—a wild hope.

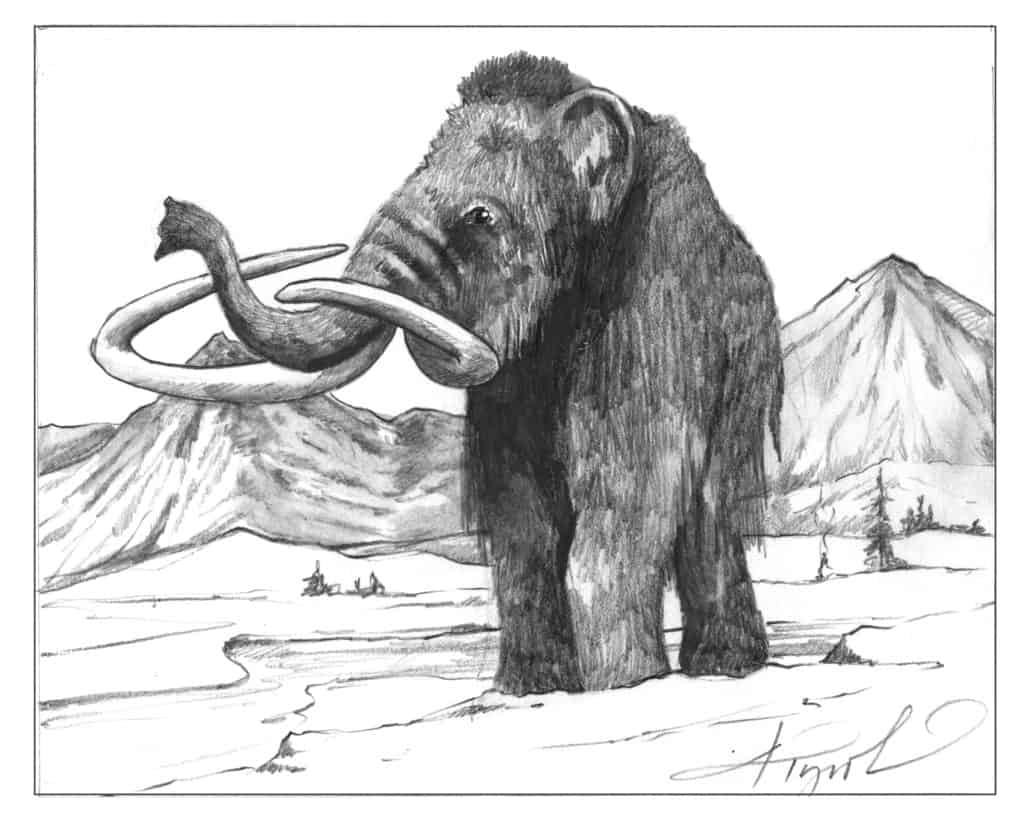

I like to imagine, especially on chilly mornings, a herd of woolly mammoths trundling out across a tundra-like landscape. The solid ground shakes as each adult mammoth, weighing close to 6 tons and standing between 9 to 11 feet tall at the shoulder, uses enormous tusks to root in the snowpack, searching for a nibble of tundra grass.

The woolly mammoth was king of the cold and its body had many adaptations to life in this frozen kingdom. Most obvious was its woolly coat, with long coarse hairs, some measuring up to 3 feet long. This skirt of hair functioned much like a yak’s, giving the mammoth protection from wind and a furry barrier to the cold ground when resting. Using patches of recovered fur and skin from preserved mammoths in Siberia, scientists have been able to reconstruct the mammoth’s complex pelage. Their coat was made of three types of hair. Closest to the thick skin, which had an underlying 4-inch layer of fat, the mammoth was covered with dense wavy under-fur. Long guard hairs were next, and then the thick over-hairs that formed the mammoth’s skirt. Using microscopic technology, researchers determined that each hair grew in the skin individually and had its own oil gland, which helped to insulate the massive body. The variation of fur, along with the oil, thick insulating skin, and subcutaneous fat layer gave the woolly mammoth a shaggy shield from the Ice Age’s deep freeze.

Woolly mammoths might have been giants of the age, but they had rather petite ears and a tiny, almost Eyeore-like tail when compared with modern-day elephants. This was an important adaptation since big ears and long tails would have led to a loss of critical body heat. They did have extra-large feet with soles that were 13.5%arger than the similar-sized African elephant’s feet. In essence, the woolly mammoth had built-on snowshoes, which spread its massive weight across a large surface area and facilitated its movement through deep snow.

Studies of preserved mammoth trunks find that they had a hood-like extension at the tip. This is not something found on current elephants. Scientists theorize that when woolly mammoths weren’t using the extension to shovel and grasp snow, the flap worked like a snuggly fold to help keep the un-woolly tip of the trunk warm.

The woolly mammoth’s exterior wasn’t the only way this mammal was adapted to subzero temperatures and arid icy conditions. The iconic hump on the upper neck and back is thought to be a reservoir of energy-storing brown fat and water, functioning much like a camel’s hump. This adaptation made it possible for the mammoth to survive when the ice age conditions became even more extreme and there were food and water shortages.

Woolly mammoths were special. They survived an epoch of weather that would make our worst snowstorm look like a day at the beach. But when the climate began to change, the mammoths were pushed beyond their limits. It’s been a long time since a mammoth walked in my backyard over 10,000 years ago. But if I stand very still with my hand on a granite rock, I might just be touching something that once touched one of these remarkable creatures.

Susie Spikol is the community program director for the Harris Center for Conservation Education in Hancock, N.H. The illustration is by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is edited by Northern Woodlands magazine, sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of N.H. Charitable Foundation.