By Meghan McCarthy McPhaul

The big white birds paddling gracefully across a Massachusetts pond last November surprised me. I’d grown up in the town I was visiting and had never seen swans there, although my friend assured me they were resident birds. The only mute swans I’d seen before, years ago, were floating along the River Thames between Eton College and Windsor Castle.

Swans in England have a long history, and the mute swans along the Thames are, by law, the property of the queen. Mute swans on our side of the Atlantic are a more modern phenomenon and have no such protection. In fact, wildlife managers have been working for years to diminish the population of this species in order to protect native habitat and waterfowl.

While tundra swans and trumpeter swans, both native to North America, occasionally pass through our region on their way to and from northern breeding grounds, the larger mute swans are not native. They were introduced as adornments to parks and estate ponds in the nineteenth century and have since made their feral way around New England and further afield, from the Chesapeake Bay to the Midwest and the Pacific Northwest.

While tundra swans and trumpeter swans, both native to North America, occasionally pass through our region on their way to and from northern breeding grounds, the larger mute swans are not native. They were introduced as adornments to parks and estate ponds in the nineteenth century and have since made their feral way around New England and further afield, from the Chesapeake Bay to the Midwest and the Pacific Northwest.

Mute swans are among the largest birds in North America. Males weigh up to 30 pounds and measure more than four feet from beak to tail, with a wingspan stretching toward eight feet. They are beautiful birds, with pure white feathers and s-curved necks, but their impact on native habitat and other waterfowl is less appealing.

“They raise havoc with the native species,” said Jessica Carloni, waterfowl project leader for the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department.

Voracious and aggressively territorial, mute swans eat up to eight pounds of aquatic plants each day, uprooting several more pounds as they forage. They skim plants from the surface of water, and also rake the bottom with their feet to bring up additional vegetation. They can consume plants – grasses, pondweeds, and others – faster than the plants are able to recover.

Mute swans establish breeding territories on fresh, brackish, and saltwater ponds, as well as slow-moving rivers, bogs, and inland streams. Despite their serene posture on the water, these birds do not play nicely with others and are unlikely to share territory with other species of waterfowl. Besides chasing ducks, geese, and gulls away from their nesting sites, mute swans will also go after dogs and humans who wander too close to a nest.

One of the reasons that people have a fondness for these birds is their tendency to remain in pair bonds over multiple years. They build their homes together, with the male identifying multiple potential nest sites, and the female having the final say in where they settle down. The male begins the nest construction by assembling a platform of crisscrossed vegetation, then collects additional materials – reeds, twigs, cattails, sedges, and grasses – for the female to continue the building, piling the materials onto the nest and using her feet and body to form a custom-molded concavity in a nest that may be five feet across and two feet high. Both male and female may add to the nest during egg-laying and while brooding chicks.

Their population, estimated at fewer than 1,000 in 1950, climbed significantly from the mid-1900s to the turn of the 21st century. The reference book “Ducks, Geese, and Swans of North America” by Guy A. Baldassarre estimates some 13,650 mute swans living in the Atlantic Flyway – the migratory channel running from eastern Canada to Florida – in 2005, with populations dropping to 10,500 in 2008 and to 9,700 by 2011.

The recent drop is likely the result of efforts to stop mute swans from reproducing, as well as active culling of the species. Several states along the Atlantic Flyway – including Maryland and New York, where mute swans have decimated populations of skimmers and terns – have formal management plans in place, which include lethal action in some instances. Others, like New Hampshire, take a more passive approach, namely discouraging mute swan reproduction by addling eggs in the nest.

“We care about our native waterfowl,” Carloni said. “A lot of folks try to stop invasive vegetation. This is similar.”

Finding ways to knock off purple loosestrife or Japanese knotweed, however, is considerably less controversial than developing a management plan – any management plan – for reducing the number of mute swans. As Carloni noted, “People get really attached to these birds,” and don’t recognize their harm to local ecosystems.

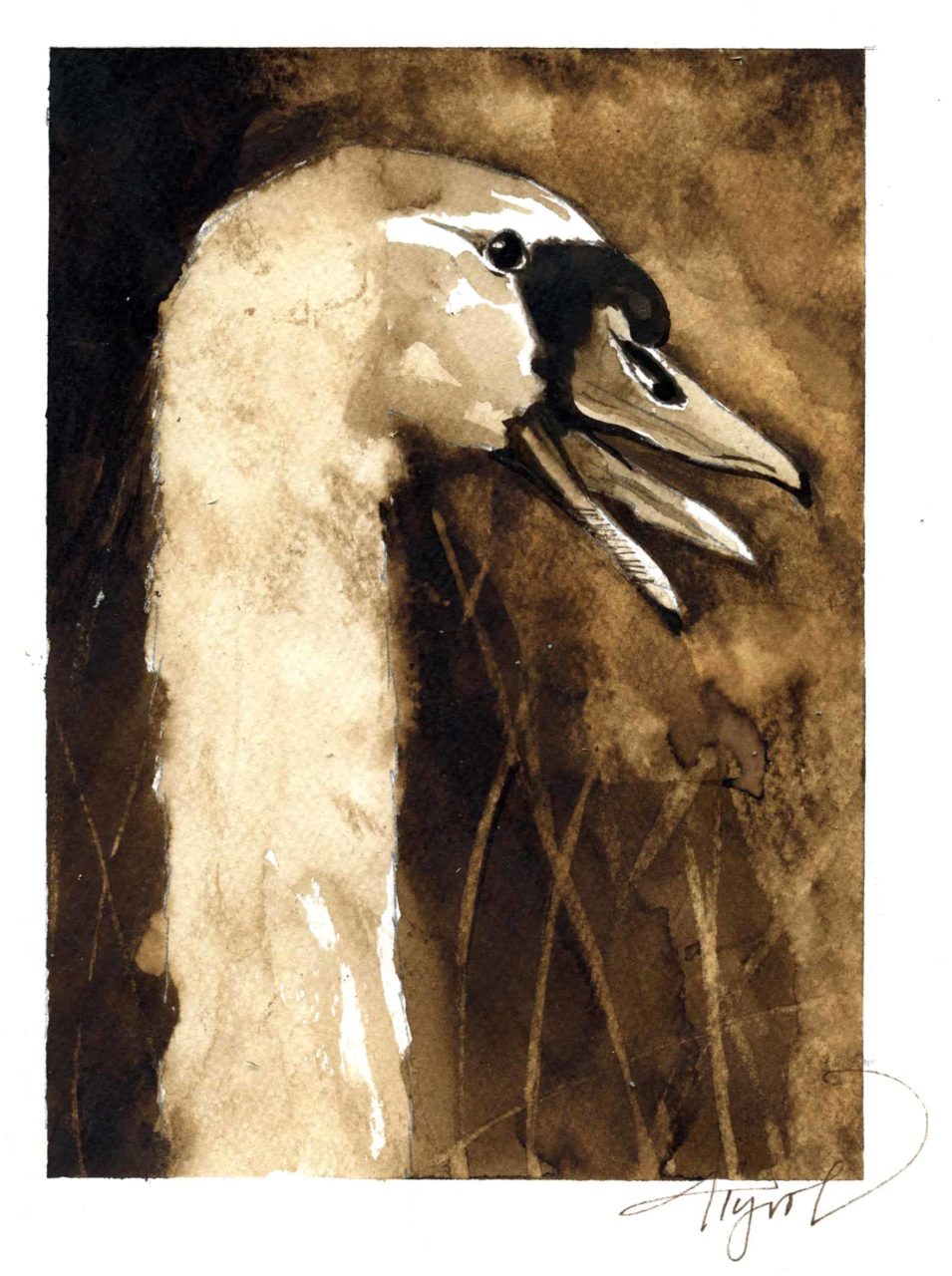

Meghan McCarthy McPhaul is an author and freelance writer. She lives in Franconia, N.H. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine: northernwoodlands.org, and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: [email protected]