By Meghan McCarthy McPhaul

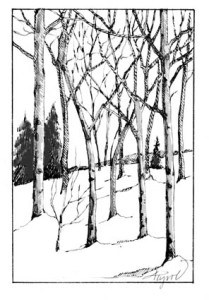

Near the house where I lived during my Colorado years, there was a trail that wove through a sprawling grove of perfect quaking aspen trees. In spring, the soft green of emerging leaves was one of the first signs of warming weather. Come fall, their gilded leaves, fluttering in the breeze, reflected in the river, turning everything to gold. Even in winter’s rest, their stark trunks and bare, branching limbs were lovely against a backdrop of deep snow and craggy mountains.

Except the trees weren’t really resting. Little did I know that, even shorn of their leaves, they were still harvesting sunlight.

Quaking aspen – Populus tremuloides – is one of our continent’s most widely distributed trees, stretching from Alaska and Canada all the way south to Mexico and east to our region. Also known as golden aspen and trembling aspen, it’s distinguished by flat-stemmed leaves that flutter in the slightest breeze. The tree grows at elevations as high as 10,000 feet and thrives in cooler climates. Like other cold weather species, it has evolved ways to make the most of harsh growing conditions, including an ability to capture energy through its bark.

Quaking aspen – Populus tremuloides – is one of our continent’s most widely distributed trees, stretching from Alaska and Canada all the way south to Mexico and east to our region. Also known as golden aspen and trembling aspen, it’s distinguished by flat-stemmed leaves that flutter in the slightest breeze. The tree grows at elevations as high as 10,000 feet and thrives in cooler climates. Like other cold weather species, it has evolved ways to make the most of harsh growing conditions, including an ability to capture energy through its bark.

Well, not exactly the bark. Photosynthesis happens in the cortex, which Kevin Smith, supervisory plant physiologist for the U.S. Forest Service’s Northern Research Station, described as the tissue remnant from the cell division of tip growth. The cortex lies between the bark and the tree’s vascular system.

It turns out some other trees also have the ability to photosynthesize in their cortex, at least to a limited extent. “Many northeastern species of both conifer and broadleaved trees can conduct photosynthesis in young portions of stems and branches,” said Smith. “Scratch the surface of current year branchlets of maple, pine, oak, apple, or poplar with your thumbnail, and you will likely see green coloration, just beneath the bark.”

That green indicates the presence of chlorophyll, the same stuff found in green leaves. (As a refresher, photosynthesis is the complex process in which plants use sunlight and chlorophyll to transform water, carbon dioxide, and other components into carbohydrates, releasing oxygen along the way.)

Where quaking aspens have the advantage over many other trees, is the length of time their limbs and branches can harness energy.

“After a year or two, in most species we’re familiar with, you’re not going to find that green layer,” Smith explained. “It’s sloughed off. It’s not there anymore.”

The bark of quaking aspen, however, stays relatively thin for several years, permitting light to pass through. Additionally, the tree retains a high number of lenticels – structures in the small openings of bark that allow the tree to exchange gases, or “breathe.” These openings also allow sunlight to reach the cortex.

There are, of course, other factors required for photosynthesis, including a temperature somewhere between about 45 to 85 degrees. While winter temperatures are often below that range, quaking aspens take advantage of sunlight filtering through leafless branches to warm trunks. So, even if the temperature hovers around freezing, the sun-warmed trees can be harnessing energy.

Winter photosynthesis has another benefit, beyond adding to the trees’ energy budget: it helps provide oxygen to the living cells that would otherwise be deprived. In this way, it maintains the health of the sapwood, which transports water and nutrients through the tree.

In addition to its golden good looks and winter survival skills, there are other reasons to appreciate this tree. It’s a great source of habitat and food for wildlife. Considered a “pioneer” species, quaking aspen thrives in areas disturbed by events like fire, logging, or landslides. Sunlight filtering through its leaves allows other tree species to get established. Numerous animals, from porcupines to moose, eat its bark, leaves, twigs, and buds. Ruffed grouse, especially, depend on quaking aspen for shelter and food, eating the buds through the winter and catkins in the spring.

Meghan McCarthy McPhaul is an author and freelance writer. She lives in Franconia, N. H. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine: northernwoodlands.org, and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: [email protected].