By Declan McCabe

My three children have participated in a Four Winds Nature Institute program that recruits adult family members to lead grade-school nature learning. I have worked with several moms and dads over the years to pull together materials for hands-on lessons about communities, habitats, and the natural world. The activities usually ended with crowd-pleasing puppet shows.

During my first year in the program, in a rare moment of advance planning, I read the entire year’s program and was glad I did: “Snags and Rotting Logs” was scheduled for November, when I anticipated most logs would be frozen or buried in snow. Regardless of frost or snow, I expected that some interesting invertebrates would have tunneled deep into the soil to wait out Vermont’s winter, leaving little more than wood for the students to dissect.

So I pushed a wheelbarrow into Winooski’s Gilbrook Nature Area in September to load up with logs for November. I poked a screwdriver through the bark of each log to confirm that wood was sufficiently rotted to host a diverse community before bagging them for cold storage. I had stacked the odds in favor of success by selecting only the “best” logs: my poking and probing quickly focused my attention on birch.

The point of the Four Winds lesson is to show how snags (standing dead trees) and downed logs, while no longer growing wood, are very much alive with other organisms. Fungi that weakened trees and hastened their return to earth continue releasing enzymes and are joined by

soil fungi, further breaking down cell walls. Insects and other invertebrates, incapable of digesting wood without the help of fungi and other microorganisms, draw sustenance from the decomposing debris. Carpenter ants dine elsewhere, on sweet or high-protein foods, but they nest in decaying wood.

This early invasion of dead wood sets the table for larger creatures. Shrews, moles, and insectivorous birds chow down on the abundant six-legged, protein-packed morsels. Woodpecker activity opens up the logs to the elements, accelerating the breakdown and release of nutrients from the wood to forest soil. Pileated woodpeckers are a good indicator of mature forest conditions, including snags for nest sites and logs in various states of decomposition.

For woodpeckers’ purposes and mine, not all logs are created equal. Some, such as black locusts planted in years past to grow fence posts, take a long time to decompose and are therefore poor hosts for invertebrates. Researcher Grégoire Freschet and colleagues in Holland modeled log decomposition and showed that alder, willow, and poplar lose most of their density to decomposition in eight years; logs from pine roots were far tougher, lasting four times as long. However, all of these trees share one characteristic that made them less interesting for my purposes: the bark tends to rot first.

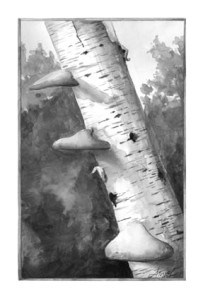

Birch flips the decomposition process on its head. The wood rapidly rots to crumbly pulp while the bark, protected by antifungal compounds, persists as an intact cylinder. These “birch pipes” can serve as important habitats for invertebrates. With a long-bladed shovel, it’s easy to lift an intact yet very rotten birch log into a bag along with all of its inhabitants.

Birch pipes have been a great way for children in our Four Winds program to make hands-on investigations, discovering how rotting logs are essential habitats for centipedes, millipedes, sow bugs, beetle larvae, and ants as well as the birds that depend on them for food.

I must come clean at this point and admit that the first time I provided logs for the classroom, I sweetened the pot by adding night crawlers. The children found the night crawlers along with other earthworms and more than a dozen invertebrate species that had not required my real-estate services.

The thrill of “the hunt” through decomposing logs is a good example of how kids ’ science instruction doesn’t always require fancy equipment; often all that is needed is outdoor materials and time to explore. Through fun activities, children and adults learn together to appreciate that nature is everywhere, and that our fellow travelers are fascinating.

This year, with the delay in cold weather, it may still be warm enough to slide a shovel under a log for study. If you do, I recommend a well-rotted birch log.

Declan McCabe teaches biology at Saint Michael’s College. His work with student researchers on insect communities in the Champlain Basin is funded by Vermont EPSCoR’s Grant NSF EPS Award #1556770 from the National Science Foundation. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine, northernwoodlands.org, and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: [email protected].