By Elise Tillinghast

Every year around this time, my husband, kids and I haul out the tent blind from our garage and set it up in the field in front of our house. We toss in a few folding chairs, a thermos, maybe a neighbor. At dusk, we take our seats.

First come the vocalizations — what are officially called “peents,” but sound more to us like the name Bert repeated in a froggy voice. A male American woodcock materializes — we never see the moment of arrival — and makes his way across the winter-flattened grass. His goal is to impress females hiding in the tree line, although I suspect he makes an impression on predators, too. He looks vulnerable, and more than a little ridiculous, with his plump shorebird body, letter-opener beak, and eyes positioned far back on his head.

The woodcock struts and peents a few more times and then he’s gone, rocketing upward in a spiral pattern that’s difficult to track. As he rises there’s a fast, high pitched wheedling, a sound that I once assumed was his voice, but now know is the effect of his outermost primary wing feathers sawing the air. He flies high, 300 feet or more above us, and vanishes against the darkening sky. We find him, loudly chirping, as he dives back to earth. He lands close to where he started, struts, peents, and takes off again.

Spying on woodcock courtship displays is a family tradition and a cherished way to turn the page to spring. It’s also a low-key way to introduce our older child to the concept of habitat management. Over time, in overly-earnest parent fashion (but served in a tent with hot chocolate!) we’re explaining to our daughter how our land, along with that of our neighbors, shelters and nurtures a bird she loves.

The American woodcock requires a combination of habitat types. Good feeding sites have rich, soft soil; although woodcock will consume a variety of insects and other invertebrates, their main food is earthworms, and they hunt this prey by poking their sensitive bills into the ground. Woodcock also need protection while they eat; as we tell our daughter, it’s hard to enjoy a restaurant when you’re listed on the menu. Thick cover such as an alder stand, or regenerating hardwood forest, offer favorable conditions.

Where we live, along the western branch of the Ompompanoosuc River, there are plenty of shrubby, damp areas that offer good feeding prospects. The site where we harvested timber from about seven years ago — which is today full of young tree growth and blackberry bushes — often has evidence of woodcock-bill holes. I’ve observed that woodcock will take advantage of cover provided by invasive honeysuckle; since our land has more than its share of this noxious weed, I guess it’s nice that the plant has some positive aspects.

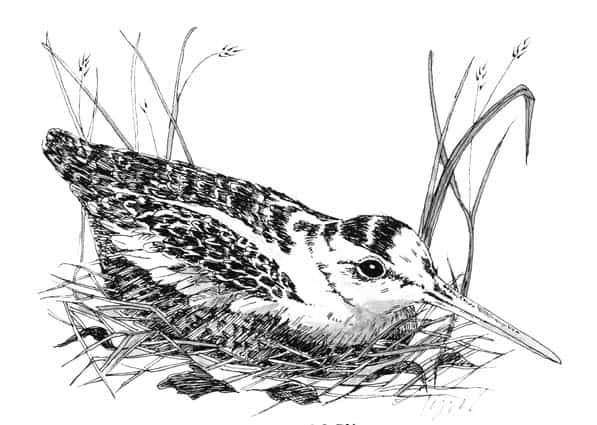

Nesting areas often overlap with feeding areas, but woodcock management guides typically describe nesting sites as a bit drier, and perhaps a bit higher, with a little more open ground. A typical site is a stand of sugar maples that we manage for bird habitat (or more accurately, our forester manages, with input from Audubon Vermont’s Foresters for the Birds program). We have witnessed hens there demonstrating their broken wing trick: this is when they attempt to lure a predator out of their nesting areas with crooked, low-to-the-ground flight. Woodcock hens brood on the ground, and a nest doesn’t look like much — a shallow impression of leaves that blends in with the immediate surroundings.

Nests are generally built within 150 yards of a courtship area (“singing ground”). One of the most frequent places we have seen hens is in a small patch of trees and shrubs that surround and grow on top of a giant rock outcropping in our field. These sightings have been sufficiently frequent that we avoid the area during peak nesting season, which extends from April through May.

Woodcock need open space not just for courtship displays in spring, but for summer nighttime roosting. Shrubby pasture is great for this, as are recently cleared areas such as log landings. Maintaining such open spaces, or creating new ones, can encourage the birds in landscapes that are otherwise dominated by older forest habitat.

I’d be lying to say that my daughter listens with rapt attention, as my husband and I drone on about habitat issues. But I think, I hope, that by continuing to share with her the connection between how we manage our land and a favorite bird’s aerial feats, we’re instilling in her not just a love of nature but an understanding that she can help to care for it. That seems like a fitting message for spring.

Elise Tillinghast is the publisher of Northern Woodlands magazine. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine: northernwoodlands.org, and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: [email protected].