Fred Harris began ski jumping in Brattleboro as a teenager, using skis he had made for him at a local wood shop. Harris later attended Dartmouth College, where he promoted outdoor recreation of all sorts. Above, he jumped during the winter of 1911, the year he graduated.

By Mark Bushnell/VT Digger

If Fred Harris’ diary is any guide, it’s a miracle that skiing ever caught on. “[L]anded hard,” the Brattleboro native wrote one January day in 1904. “Tore the strap off the buckle part of my footgear. Hurt my back some. My skee [ski] went away and left me on another dump. Dark when [I] came home. … I am tired.”

In reality, Harris couldn’t have been having more fun — despite the falls, equipment failures and injuries. He was one of those stout-hearted people who, in looking for adventure, helped pioneer skiing in the East.

Many people at the start of the 20th Century seem to dread the onset of winter. Engaging in any form of outdoor recreation was foreign to many. Sure, snowshoeing, skating, sleighing and sledding were popular with some people, but none of those sports had the type of following that would attract large numbers of visitors to the state. None, in short, would have the impact on Vermont that skiing would.

Fred Harris would eventually attend Dartmouth College, where he founded the Dartmouth Outing Club. That group would be mimicked by students at other colleges and help foster the growth of intercollegiate ski competitions.

Later, Harris would serve as president of the U.S. Eastern Amateur Ski Association and represent the nation at the Federation Internationale de Ski Congress in Norway.

But in 1904, Harris was a teenager who was only interested in fashioning a decent pair of skis. He had little choice but to make his own. The general belief among the few Americans who skied was that the only source for quality equipment was Norway.

So Harris had a local shop cut out a pair for him to his specifications. His orders called for skis that were 8 to 9 feet long and more than 5 inches wide.

Harris seems to have been regularly in the market for a new pair. Sometimes it was because he wanted to try a new design he had dreamed up; other times, it was because he kept snapping his skis.

Harris purchased leather straps from area harness makers and screwed them to his skis, then used buckles to secure the straps to his boots. For a pole — in the early days, skiers only used one — he liked using pine to fashion the 9-foot-long shaft.

The reason Harris took so many spills was that, despite skiing on what must have been remarkably unresponsive skis, he insisted on using them to jump. Despite his cumbersome equipment, Harris quickly became quite proficient. “Could clear 15 feet,” he wrote in his diary on Feb. 17, 1904. A year later, he could soar 50 feet.

(In 1922, the Harris Hill ski jump was built in Brattleboro and named for Fred Harris. The Olympic-size 90-meter jump will celebrate its 100-year history with a competition Feb. 19 and 20.)

Skiers warm themselves and relax in a hut built by Woodstock farmer Clinton Gilbert in this circa 1940 photo.

A hard slog uphill

Most skiers, however, were drawn to the sport for the downhill schussing, not the jumping. With no trails cut for the sport, skiers sought out steep open fields or logging roads to ski down.

Most of their time, however, was spent climbing uphill, not skiing down it. A fit skier might manage six runs in a day.

A group of skiers, gathering at the White Cupboard Inn in Woodstock one evening in January 1934, bemoaned the fact. As the skiers, a group of young businessmen from New York City, sat around complaining of sore muscles, they hit upon an idea.

“(E)ach of us is spending $40 apiece to enjoy a weekend in Vermont,” one of the men told the innkeepers, “yet the most we can do in a day is to climb a hill half a dozen times. We want to get in all the skiing we can on a weekend. We want to be carried uphill.”

In short, they wanted to create a more favorable ratio of downhill exhilaration to uphill slogging. So they pledged at least $75 to the inn’s owners, Robert and Elizabeth Royce, if they could come up with a mechanized way to transport skiers uphill. The skiers said they would be back in mid-February and asked the Royces to have something in place by then.

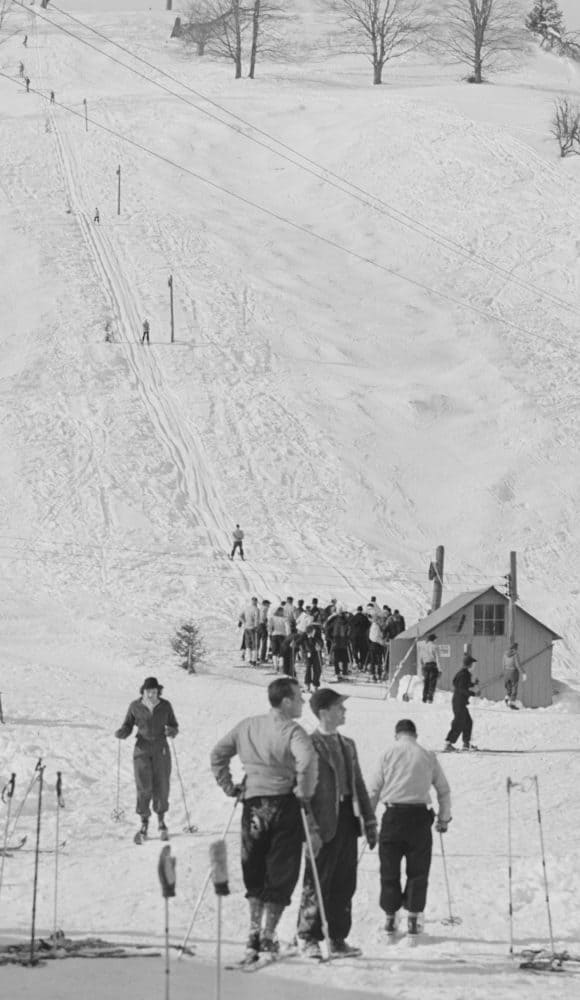

Woodstock had the first rope tow in the United States, which was installed at a local dairy farm owned by Clinton Gilbert.

Despite the short deadline, the Royces succeeded. They tracked down a rumor that a ski club in Quebec had such a device — no easy feat in the days before Google. Using a crude diagram provided by the club, a couple of talented mechanics hired by the Royces set to work. The main parts were 1,800 feet of rope, some pulleys and an old Model T Ford truck to power it.

The result was the first rope tow in America.

The total cost came to $500, which the skiers gratefully paid. The Royces had the tow set up on a sloping pasture they leased from local farmer Clinton Gilbert. Tow ropes transformed skiing from a sport open only to the most physically fit to one that almost anyone could try.

An overnight impact

The Royces’ tow had an equally startling effect on Woodstock. Suddenly, the town became a skiing mecca. Ever since the Woodstock Inn opened in 1892, the town had been a fashionable destination for outdoor recreation. But this was something different.

“The hundreds and hundreds of skiers who thronged the streets on Saturday nights, overflowed the eating-places, and startled housewives with requests for beds, bewildered the sober citizenry,” wrote Charles Crane in his 1947 book “Winter in Vermont.” “Every third house along the main roads hung out its ‘Skiers Accommodated’ sign, winter-idle youths took to taxi-driving, and new tows were quickly constructed to meet the overwhelming demand.”

Almost overnight, winter had gone from being a time to endure to one to embrace.

Railroads, seeing great potential in the ski traffic, began running more trains to the ski areas that were popping up across Vermont. In the mid-1930s, Woodstock had a lot of company. Soon seemingly every town with steep, open fields and access to good roads or a train station had its own ski area.

A state report issued in 1938 lists 33 communities offering skiing. Many of them — including Barre City, Barton, Brandon, Fair Haven and Shrewsbury — have left their skiing days far behind. Others on that list, towns like Sherburne (now Killington), Cambridge and Stowe, remain mainstays in Vermont’s skiing industry.

Woodstock’s own winter prosperity came despite one obvious disadvantage — it was 14 miles from the nearest railroad station. But Woodstock being Woodstock, Crane wrote, that was also something of an advantage.

“Some people bemoan the fact,” he wrote, “but others point out that there is little pleasure or profit in playing host to an army of Sunday excursionists, who, as they say, leave nothing but dents on the slopes and little cash on the barrel-head.”

Starting in the 1930s, cars carrying skis became a regular sight on the streets of Woodstock and other Vermont communities with ski areas.