By Bruce Bouchard, a Q&A with John Turchiano

John Turchiano, a retired union official and a close friend of 50 years, and I often talk baseball. What follows is from a chat we had recently about Jackie Robinson and the reversal of the color barrier in baseball, which happened 80 years ago this week — April 15, 1947 — when Robinson first took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

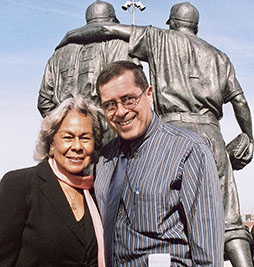

Courtesy John Turchiano

Rachel Robinson and John Turchiano at the dedication of the Jackie Robinson-Pee Wee Reese monument outside MCU Stadium in Brooklyn, New York on Oct. 1, 2005. Rachel Robinson is 101 years old and still active in various causes.

Bruce Bouchard: John, I have been thinking about Jackie Robinson and the upcoming 80-year anniversary of the reversal of the color barrier. I know nothing about the root of the reversal. Was it a movement or the brain child of like-minded, right-thinking people?

John Turchiano: It has a surprising evolution. This is a story that even your father, Gene Bouchard, one of the great baseball fans of all time, didn’t know!! Blacks may have been freed from slavery as a result of the Civil War, but they certainly weren’t free from discrimination. Jim Crow reigned throughout the South and elsewhere, and miscegenation laws abounded. Bigotry was everywhere, including baseball, which banned Blacks beginning in the 1880s. But a gradual change began.

BB: Who initiated the change, who manned the wheel?

JT: So many progressives were involved. As examples, In the 1930s New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia demanded the integration of the city’s police department. The country’s First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, spoke out in favor of civil rights. Rabbi Stephen Wise famously campaigned for equality. Other progressives joined the chorus for change.

When World War II broke out more than one million Blacks joined the U.S. military. They comprised 10% of America’s armed forces but to our country’s everlasting disgrace they were segregated from White soldiers and often given menial jobs to do. This nevertheless was followed by quiet progressive steps. Broadway’s Stage Door Canteen and the West Coast’s Hollywood Canteen, clubs dedicated to having celebrities entertain and personally serve our troops during World War II, treated Blacks and Whites equally.

BB: Not to digress, but the canteens were such rich and textured stories. A great idea for a 21st Century dive back into that culture, including artists leading the way to full integration.

JT: Yes! There were a number of films that highlighted the canteens, mostly as boulevard entertainments, but the story could be told today in a different light of full exposure.

These venues were fully integrated. There was no separation of the races at the canteens or in Broadway theaters. But baseball’s color line continued to bar Blacks from playing the national pastime and the U.S. military continued its segregation of troops.

At the same time, it is important to note that Blacks weren’t the only group suffering from bigotry. In fact, it was not discrimination against Blacks that eventually dismantled baseball’s color barrier. It was anti-semitism. Until 1945 the country’s medical community conspired to limit the number of Jews allowed to become doctors. An immeasurable number of bright Jewish students were denied admission to medical schools. And then, the littlest known big event happened. As Roger Kahn pointed out in his book “Rickey & Robinson,” when a dean of Cornell’s Medical College testified before the New York State legislature in 1944 and said a quota in admissions indeed existed, there was outrage. He said that regardless of how many Jewish students applied to the school no more than 5 percent of the freshman class “could be followers of the Hebrew religion.” This was not welcome news in New York City, where Jews were a large and powerful voting bloc, and this led to the 1945 passage of the Ives-Quinn Act, which was a real game changer — quite literally.

BB: Perhaps I slept through this class, but I find this to be a stunning reveal. I knew absolutely nothing about the linkage between anti-Semitism and the end of the color barrier.

JT: You are not alone, and I can’t imagine you sleeping through any class. No one talks or even knows about the Ives-Quinn Act today but it surely deserves an honored place in the halls of history. Its significance is undeniable. It made job discrimination a crime in New York State. It set up the State Commission against Discrimination, now called the New York State Division of Human Rights. The law’s impact was immediate, and not just on Jews who wanted to become doctors. When the Ives-Quinn Act was passed, it led Jackie Robinson of the Negro League’s Kansas City Monarchs to tell his wife, Rachel, that it could give him a chance to play in the Major Leagues.

Robinson was right. At the time of its enactment, the Ives-Quinn Act became the strongest ban on racial and religious discrimination in the United States. It should be noted that it was enacted by an overwhelming bipartisan vote, and signed into law by a Republican, New York State Governor Thomas Dewey. Not only did it bring about more Jewish doctors and other big changes, it led Branch Rickey, the general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, to immediately prepare for the integration of his team. Rickey had wanted to integrate baseball for a very long time and the Ives-Quinn Act gave him the chance to do so. On Oct. 23, 1945, a few months after the Ives-Quinn Act was passed, Rickey signed Jackie Robinson to a Brooklyn Dodgers minor league contract, officially breaking baseball’s color barrier. Robinson made his Major League debut on April 15, 1947.

BB: And that’s when teams in the National and American Leagues began finally signing Blacks?

JT: Yes, but even after the debut of Jackie Robinson many of the Major League team owners remained bigoted. According to Roger Kahn, although Jackie Robinson was signed by the Dodgers the team’s owner, Walter O’Malley, told Daily News sports columnist Dick Young, “I want to leave Brooklyn because the area is getting full of blacks and spics.” O’Malley kept his word, too. He shepherded his team out of Brooklyn in 1957.

And while the signing of Jackie Robinson opened the door to Blacks playing in the major leagues, the integration of baseball was still slow. The New York Yankees didn’t sign a Black player until 1955. The Boston Red Sox waited until 1959, a full 14 years after Jackie Robinson was signed. And it took baseball 28 years after Jackie Robinson won the National League’s 1947 Rookie of the Year award for the Major Leagues to have its first Black manager, Frank Robinson.

The integration of the national pastime turned out to be a monumental step in civil rights. It really shook up our country, and in a very good way. The year after Jackie Robinson first played for the Brooklyn Dodgers President Harry Truman ended segregation in the U.S. military. The U.S. Supreme Court outlawed segregation in public schools six years later. The Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act followed in the 1960s.

BB: Any other interesting notes about the end of baseball’s color barrier?

Oh, yeah. The Yankees should have signed a Black player much earlier than 1955. But outright racism prevented that. We know this from Kahn and other baseball writers.

It seems in 1949 the Yankees sent one of the team’s scouts, Bill “Wheels” McCorry to look at Negro League games in Alabama. McCorry, a racist, reported that among other players for the Birmingham Black Barons was an 18-year-old that didn’t impress him very much.

His scouting report said, “He can run some and can throw a little, but the boy isn’t worth signing because he can’t hit a good curve ball.” In subsequent years that scouting report has come under intense scrutiny. Many believe the Black youth the bigoted McCorry scouted was a far better player than his report indicated — a player the Yankees could have signed for a small bonus. Relying on the biased McCorry’s scouting report, however, the Bronx Bombers made no offer to the youth. Today, there’s a good lesson in this story. Yes, racism is reprehensible. But it’s also pretty damn stupid. You see, if the Yankees had signed that 18-year-old Black kid in 1949, their outfield for the 1951 season would have been baseball’s holy trinity: Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays.

BB: DiMaggio, Mantle and Mays . . . quite a distinctive ring. Thanks for yet another great talk about one of our favorite subjects. And thanks for the shout-out to my Dad, who gave me the game. I miss him every day.