If you take to the water this spring, there’s a good chance you’ll spot a great blue heron, New England’s most recognizable large wading bird. But you might also see one of several other similar species that breed in or pass through our region’s wetlands. Telling these large waders apart can be tricky. What distinguishes a heron from a bittern from an egret? All three have long, stilt-like legs; extendable, serpentine necks; and skulk through aquatic habitats plucking prey from the shallows like trained assassins.

Distinctions between these birds are minimal and, in some cases, go no further than terminology. “In a general sense, they [herons, egrets, and bitterns] are all ‘herons’ — that’s the best simple descriptor for the group of birds in the family that goes by the scientific name Ardeidae,” said Chris Elphick, a conservation biologist at University of Connecticut who specializes in wetland birds and ecosystems. Especially with herons and egrets, he said, “The two names don’t align with the evolutionary groups. There are no clear aspects of habitat, diet, or ecology that distinguish egrets from herons.”

The distinctions are a bit clearer for bitterns, which Elphick noted “nest near the ground and are not colonial” like herons and egrets. These behavioral differences, he said, help to make bitterns an “evolutionarily and biologically distinct group.”

Three heron and one bittern species breed in northern New England.

The great blue heron (Ardea herodis) is the largest heron in North America. Its slate blue body and impressive size are a familiar sight in both fresh- and saltwater habitats throughout the year in northern New England. Within a few miles of feeding sites, you might discover a breeding colony, which can contain 500 or more individual nests high up in the trees. Great blue herons are opportunistic hunters: Elphick recalled once watching herons catch rats fleeing from flooded fields. Red-winged blackbirds alighting to eat grain also became meals.

The green heron (Butorides virescens) is smaller than the great blue. This heron’s shorter legs restrict it to shallower waters than its longer-legged counterparts. A dark green head and wings and a chestnut breast help to set the green heron apart from similar species. But like other herons, the green nests communally in large, elevated colonies. Elphick pointed out that green herons will occasionally demonstrate tool use when fishing, employing twigs, insects, and even bread crusts as bait. They have also been known to dive and swim for prey.

The black-crowned night heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) behaves true to its name. While other herons roost when the sun sets, the black-crowned night heron sets out to hunt at nightfall. This heron, the most widespread in the world, is a summer resident in our region’s fresh-, salt-, and brackish water. It can be identified by its black cap and back, grey belly, and striking red eyes. It is also stockier than its relatives. The black-crowned night heron tolerates human disturbances well and, as a result, biologists use its presence in urban aquatic environments as a bellwether of water quality and environmental conditions.

The black-crowned night heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) behaves true to its name. While other herons roost when the sun sets, the black-crowned night heron sets out to hunt at nightfall. This heron, the most widespread in the world, is a summer resident in our region’s fresh-, salt-, and brackish water. It can be identified by its black cap and back, grey belly, and striking red eyes. It is also stockier than its relatives. The black-crowned night heron tolerates human disturbances well and, as a result, biologists use its presence in urban aquatic environments as a bellwether of water quality and environmental conditions.

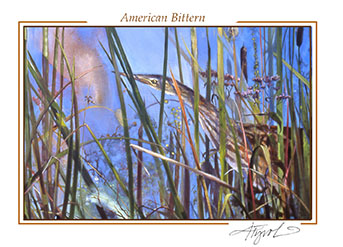

The American bittern (Botaurus lentiginosus) sticks to “densely vegetated wetlands — think big cattail marshes — where they both nest and feed,” said Elphick. “They tend to be fairly secretive and, because of the dense vegetation, can be hard to see.” Unlike herons and egrets, the American bittern shuns communal roosting and nests alone, close to the ground. Its impressive camouflage disguises it among the reeds and stalks of its environs. While you might have trouble spotting this bird, stick around a marsh in the spring and you may hear its unique pump-er-lunk vocalizations, which the Cornell Lab of Ornithology likens to “the gulps of a thirsty giant.”

Beyond these four species, you might spot other herons, egrets, and bitterns passing through. Three heron species (the little blue, tri-colored, and yellow-crowned night heron), three egret species (the snowy, great, and cattle egret), and the least bittern have all been documented in northern New England.

From the seat of your kayak or canoe this upcoming paddling season, keep an eye out. You might have the pleasure of observing one of these elegant, skilled hunters stilting through the shallows or hiding among the reeds, ready to spear its next meal.

Colby Galliher is a writer who calls the woods, meadows, and rivers of New England home. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.