Episode no. 2 of My Side of the Mountain — overlooked stories of everyday life here in the Green Mountain State. 7-minutes.

Episode no. 2 of My Side of the Mountain — overlooked stories of everyday life here in the Green Mountain State. 7-minutes.

By Ethan Weinstein

Every night, once the sun sets, JoAnne Russo switches on her porch lights. Then, she waits. As the moths emerge from the darkness, Russo is ready with camera in hand.

Vermont is home to over 2,000 species of moths, a number that continues to grow in large part because of Russo’s work.

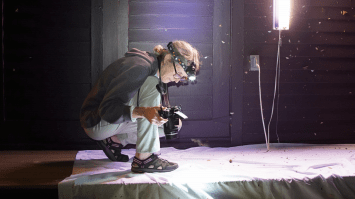

JoAnne Russo photographs a moth at her home in Saxtons River.

Every summer’s night, barring rain, she observes the moths by her home in Saxtons River, using UV lights, black lights, and regular porch lights. For about 10 years, Russo has spent her summers meticulously cataloging moths, uploading her finds to the website iNaturalist and identifying other people’s photos as well.

“As a kid, I was always collecting bugs and beetles,” Russo said. Her interest in nature led to a career as an artist. For years, Russo created meticulously woven baskets, some abstract, and many inspired by nature. In her free time, she enjoyed birding.

Fifteen years ago, Russo sought a new outdoors hobby for the summer months — a time when many birds nest out of sight. She soon took interest in butterflies and day-flying moths, but night-flying moths quickly seized her attention.

“The thing I liked about moths is literally, you just had to turn your light on, and they come to you,” Russo said.

Russo started taking photos of the moths attracted to her porch lights.

When she blew up the photos, she was amazed by the detailed patterns of the moths that looked drab at first glance. “Every night it was something different. And I just got hooked.”

You may have noticed many moths yourself — some, like the luna moth and giant polyphemus moth, rivaling bats for size. But most are small and unassuming, overlooked by most, but not Russo. She does not discriminate based on size or coloration, though the more intricate and ornate moths first caught her eye.

A good birder in Vermont might glimpse 250 bird species in a year, paling in comparison to the state’s moths. The diversity, the ease, and the ability to break new ground pulled Russo from birds to moths. She has discovered species not thought to live in Vermont. “It’s nice to contribute in some way,” she said, and with the climate crisis, more and more species are expanding their range further north.

With so little known about moths, citizen scientists like Russo can make a large contribution to the field.

She does dissections for an entomologist at Cornell University, and researchers and moth fanatics around the country send her specimens to ID. Many moths are undescribed due to their similarity to other moths, small size, and nocturnal behavior. Often, moths must be dissected to differentiate them from lookalikes. Fundamental facts remain unknown, like why the insects are attracted to light.

Already this summer, Russo has discovered a few new species for Vermont. The possibility of seeing new and rare moths fuels her nightly observations. Now, she’s replaced a single observation session with multiple viewings throughout the night. “I get up at like 3 or 4 and I come back out. Check it again. See what’s coming in, because a lot of times stuff will come in late, really late.”

Since the pandemic, she has noticed an influx of users to iNaturalist uploading their photos of their finds.

“There’s been quite a lot of new moth people lately and I think it’s because of the pandemic. No one could leave or go anywhere, so a lot of people

started just seeing what was new around their house,” she said.

“It’s just one of those passions that once you start, you can’t stop.”