The Treasury Department prints millions of notes. The following information was obtained from U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing and details what goes into creating a $20 bill and when its lifespan ends.

Paper

A $20 bill starts out life as part of a large sheet of paper. While most paper is made primarily from wood pulp, the paper used by the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing doesn’t contain any wood at all. Currency paper is composed of a special blend of 75% cotton and 25% linen. It is made with special watermarks and has blue and red fibers embedded in it along with a special security thread.

Each blank sheet is tracked from the time it leaves the mill until it is printed, and the entire shipment is continuously reconciled to make certain all are accounted for.

Printing

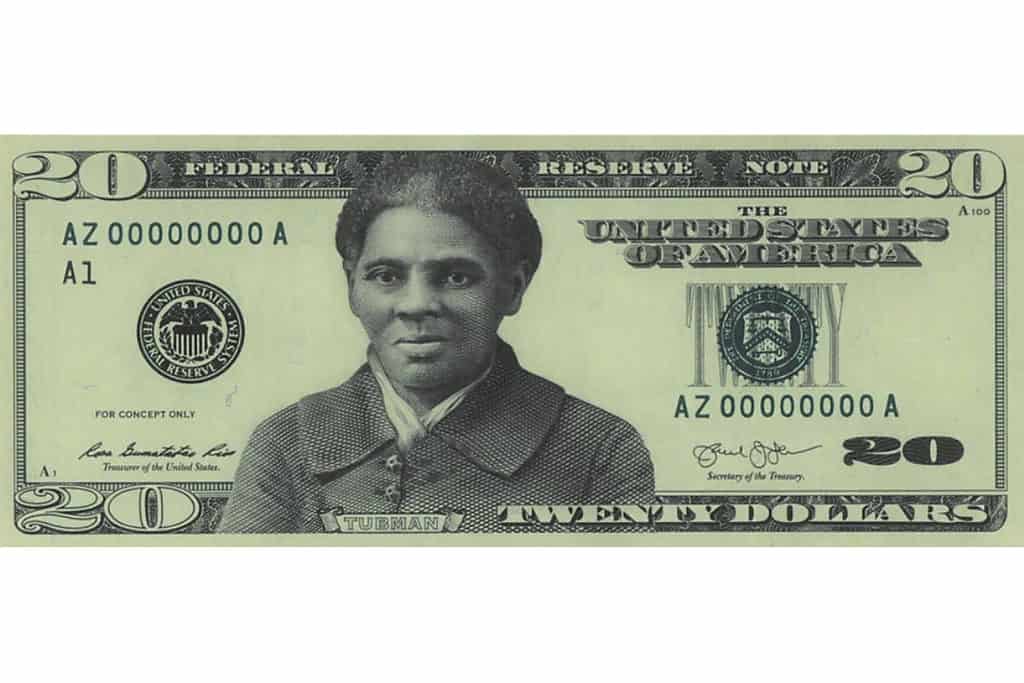

These blank sheets of cotton and linen paper get printed four times. Background images and colors are printed — both sides at once — using offset presses that are over 50 feet long and weigh over 70 tons. After drying for 72 hours, the portraits, vignettes, scrollwork, numerals, and letters are printed on the back using intaglio presses that are a mere 40 feet long and weigh only 50 tons. After drying for another 72 hours — in special guarded cages — more portraits, vignettes, scrollwork, numerals, and letters are printed on the front using theintaglio presses. Finally, the serial numbers, Federal Reserve seal, Treasury Department seal, and Federal Reserve identification numbers are printed using a letterpress.

Cutting and wrapping

Once dry, these printed sheets are gathered in stacks of 100 to be cut by a specially designed guillotine cutter. Each new stack of 100 $20 bills is wrapped with a special paper band. Ten of these 100-note stacks are gathered, machine counted, and shrink-wrapped into a bundle. Then, four of these shrink-wrapped bundles are collated together, given a special barcode label, and shrink wrapped again to create a brick of 4,000 bills, worth $80,000.

Distribution and circulation – life and death of a $20 bill

The Treasury Department ships these newly printed $20 bills to the Federal Reserve Banks, who then pay them out to banks and savings and loans—primarily in exchange for old, worn-out bills. The new bills are handed out to customers of these institutions as they withdraw cash, either through tellers or through ATMs.

An average $20 bill will change hands often, but even the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing isn’t sure how many times a bill will move from one pocket to the next. Contrary to popular belief, the government doesn’t have any way to track individual bills.

There is a polyester security thread embedded in the paper that runs vertically up one side of each bill. If you look closely, the initials USA TWENTY along with the bill’s denomination and a small flag are visible along the thread from both sides of the bill. This thread makes currency more difficult to counterfeit but cannot be tracked electronically.

Withdrawal

Banks gather worn out and damaged currency, sending it to the Federal Reserve in exchange for new bills. The Federal Reserve then sorts through these bills to determine which are still usable and which are not. Those bills deemed usable are stored until they can go out again through the commercial banking system. Those deemed no longer usable are cut into confetti-like shreds. Most are then disposed of; a small portion is sold in five-pound bags through the Treasury’s website.

Kevin Theissen is the owner of HWC Financial in Ludlow.