The Outside Story: The skinny on snakes

By Susan Shea

If you have a wood pile, you may have come across a shed snake skin ― a translucent, onion skin-like wrapper imprinted with the snake’s scale pattern. Or perhaps you’ve seen one along a foundation or stone wall. Why do snakes shed their skin?

Most animals, including humans, shed skin cells, explained herpetologist Jim Andrews, who coordinates the Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas. “The difference is that humans are continually shedding skin. Snakes shed only periodically; hence they shed the entire skin at once.”

A snake’s skin is dry and covered with scales. The scales are made of keratin, the same protein that’s found in your fingernails. Larger scales on the belly help a snake move and grip surfaces. A snake’s eyelids are transparent scales, permanently closed. Shedding, or ecdysis, replaces a snake’s old, worn skin. It removes external parasites like mites or ticks and increases the visibility of the reptile’s skin pattern. The new skin is clean and bright.

When a snake is ready to shed, it stops eating and slithers to a safe place. Its outer skin becomes dull and dry. Fluid from the lymphatic system spreads under this skin, separating it from the new skin beneath it. This fluid gives the snake’s eyes a gray or bluish cast and clouds its vision.

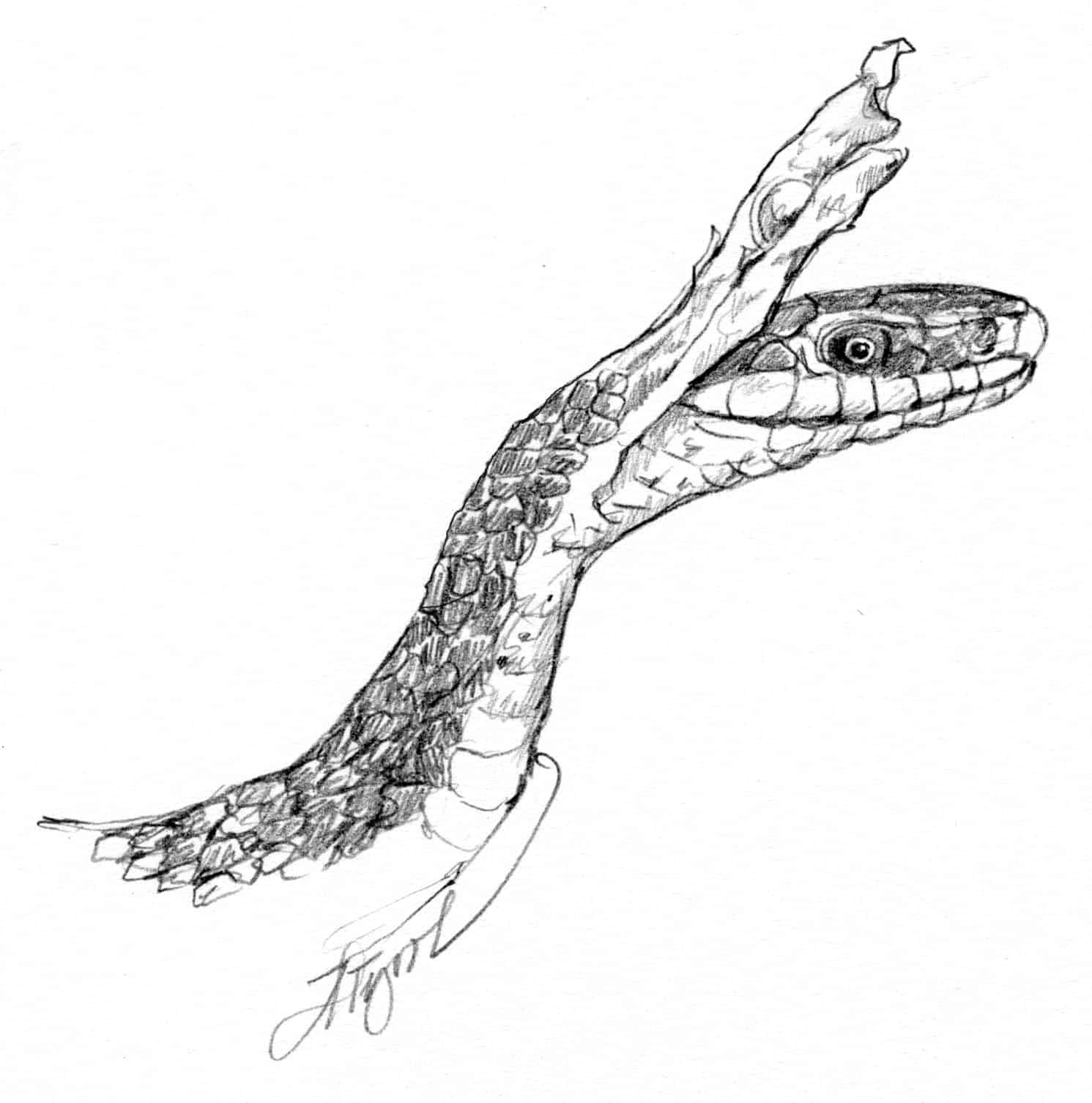

After a few days, the fluid is reabsorbed, and the snake’s eyes clear. Its body begins to expand and contract, a process that loosens the old skin. Eventually the snake rubs its nose or head on a rough surface and the old skin dislodges and begins to peel. The snake then slithers forward, turning the old skin inside out and leaving it behind, as we would take off a sock. The whole process takes several days to a week.

Andrews can identify the species of snake by holding a shed skin up to the light. He counts the number of rows of scales, the scales of each type, and notes whether the scales are keeled (ridged) or not. He has used this method to survey for snakes. Andrews has poked around in hollow trees and old sheds in Rutland County searching for the eastern ratsnake, a threatened species in Vermont, which can grow up to six feet long. He has found shed ratsnake skins hanging from rafters and rusty nails. On ledges and cliffs, he has discovered the shed skins of the milk snake, a tan snake with brown blotches, two to three feet long. Andrews has also seen the state-endangered timber rattlesnake in western Vermont. Each time a rattlesnake sheds, he said, a thickened section of the dead skin material is left attached to its tail, forming another segment of its rattle.

The frequency of shedding varies with the species of snake, its age, gender, size, reproductive state, diet, and the season. On average, snakes shed three times per year. Young snakes shed more often because they grow more quickly. Some snakes shed after hibernation, before breeding, or before egg-laying.

What happens to snake skins? Many deteriorate or are eaten by insects or other animals. Some are incorporated into birds’ nests. In the Northeast, great crested flycatchers and tufted titmice are known to use snake skins as nesting material. Flycatchers often drape a snake skin on the outside of their tree holes, and also weave skins into the nest itself. This tactic appears to be a deterrent to nest predators. In an experiment in Arkansas, where both ratsnakes and great crested flycatchers are common, scientists installed 60 nest boxes and placed either quail eggs or artificial eggs of modelling clay in each. They put one or more snake skins in 40 of the boxes; 20 boxes had no snake skin. None of the nests with snake skins were attacked by predators. Flying squirrels ate eggs in 20 percent of the nests without snake skins.

If you’d like to inspect a snake skin for yourself, or perhaps drape it in front of a birdhouse, look for shed skins this summer in firewood piles, compost containers, under loose bark, and on sunny ledges — all favorite haunts of snakes.

Susan Shea is a naturalist, conservationist, and freelance writer who lives in Brookfield, Vt. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund.

The Outside Story: The skinny on snakes