By Anita Lobel

William Edward Giles, a country gentleman, an adventurous world traveler and entrepreneur, an easy New Yorker, was born in Windsor on July 31, 1946. He died at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City on Sept. 25, 2021 after an eight year struggle with progressive anti-MAG peripheral neuropathy, a disease that chips away at the nervous system, at first gradually, and then with increasing speed robs the body of much of its function.

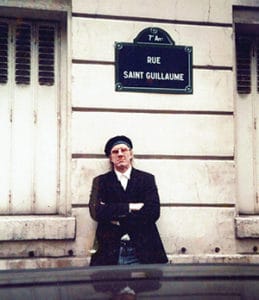

Billy Giles in Paris, 1996, under the plaque Rue Saint Guillaume.

Billy’s father, Edward Giles, was a brigadier general in the U.S. Air Force. His mother, Tina Laskiewich, a first generation White Russian immigrant, was a home maker.

A much loved only son, Billy had a typical and happy childhood of a native Vermont country boy. As a young man he hunted with his father and friends, enjoying the comaraderie of deer hunters, the cabin, the sleeping in the woods. In high school he excelled at sports. On the football team Billy played quarterback. He was a good swimmer and a fine skier. After high school graduation, intending to follow in his father’s footsteps, Billy entered Norwich Military Academy.

When his attendance at Norwich was cut short by an illness during the second semester of the freshman year, he transferred to Castleton State College (now Castleton University), where, attending courses taught by professor Tom Smith, his interests gravitated toward English, literature and ancient Greek studies. He also credited professor Douglas Stafford with interest in philosophy, and to a certain extent, classical music, especially Beethoven. Billy became a close friend of both men.

When Billy’s father was put in charge of the Soldiers‘ Home in Bennington, the family lived on the compound. Billy befriended students and professors at Bennington College and sat in on classes in poetry and art. He also worked with several noted pop artists of the time, helping to stretch canvases and loading and dispatching work destined for exhibitions. The only time he came to New York was to sell Christmas trees on the upper West Side.

In 1971, my husband and I, our 15-year-old daughter and 12 -year-old son rented a house on Lake Saint Catherine for the whole summer. Our longtime friends Tom and Virginia Smith introduced Billy to us. The instant he appeared by the lake I developed a crush on irresistible, handsome, charming “Billy Goat.” Soon whispering friends suggested, he felt the same about me.

I was married, Billy was a gentleman. The clique that gathered at the lake house throughout the summer of “Sargent Pepper” rock-and-rolled, gobbled food and drink, jumped in the lake and went dancing at a local dive where everybody knew the boys in the band. In September, my family packed up, said goodbye to summer and went back to New York City. Billy stayed in touch. A friend of the family.

Soon Vermont could not contain adventurous Billy Giles. When friends who had joined the Peace Corps invited him to stay with them in Afghanistan, he jumped at the chance. He stayed in Kabul and went on to explore the country side, easily befriending city dwellers and tribesmen. He watched the sunrise over Khyber Pass. Returning to Vermont with rustic Afghan rugs and handicrafts, he considered an import enterprise.

Billy expanded his travels to Africa and Europe. When he came through New York City, to catch flights to Kabul, to London or Lagos, he stopped with us in Park Slope overnight, sometimes longer. Each time he walked through the door my heart skipped a beat.

Billy Giles’s international enterprises began to pay off. By the early ‘80s he owned two fine cars, had taken flying lessons, qualified for an aviator’s license, bought an antique biplane, a Piper Cub, and married Bonnie McClellan.

The building of a house with mountain views in Shrewsbury was begun. The newly married Billy was settling into the life of a well-to-do Vermonter. The stops in Park Slope between international flights ceased.

On Thanksgiving afternoon in 1984, Billy boarded his Piper Cub and flew to Castleton to surprise Virginia and Tom Smith and their dinner guests. After sampling pumpkin and apple pie, he waved goodbye, climbed back into the cockpit of his biplane. On takeoff, a gust of wind caused one wing of the plane to tangle with the top of a tree. The plane crashed into the farmers field behind the Smith’s house.

Doctors did not hold out much hope for the crushed aviator. One eye was removed to save the vision in the other. A mangled foot was reset and reinforced with a steel plate. After three comatose weeks Billy sat up in bed laughing, wondering what all the fuss was about. A plastic surgeon was called in to reconstruct his face.

He required extensive rehabilitation to improve the vision in his remaining eye. That led to a several months’ stay in Outward Bound. (At the time Yvonne Daley wrote the article in Rutland Herald about the experience of his recovery.) All of this took its toll emotionally and financially. The unfinished house had to go. Billy’s and Bonnie’s short marriage fell apart.

In 1987, a few days before Christmas, no longer walking with crutches or even a cane, Billy surprised me by appearing at the doorstep of my loft in Soho. I was out of Park Slope, out of my marriage. He was healed and he was free. We were both free to begin the romance we must have always hoped would be ours.

The recovered Billy was ready for new pursuits. Friends from a Greek shipping company were planning a start-up venture of leisure submarines and put Billy in charge. He left Vermont for a beach front condo in Vero Beach, Florida. I visited often. We played house and played on the beach and explored Florida. When, after a year, plans for the submarine venture did not pan out, Billy came back to Vermont. Shortly after that he settled in with me in Soho.

In 1988 we had our “honeymoon” in Paris. We traveled to London and to Greece. In Piraeus we were offered the use of Billy’s Greek associates’ yacht. We sailed on the Aegean to Santorini and Crete. During another trip we explored Stockholm, where I had lived before coming to the States. We often took quick trips to Paris, stayed in small hotels. A few times I had rented apartments. We took one wonderful trip to the beaches of Normandy. Billy had read extensively about the June 1944 landings. He was a wonderful, informed guide.

Over a period of time Billy had developed an interest in all things Japanese, literature, the martial arts, food, and the collecting of Japanese prints. Both of us studied Japanese and traveled to Japan. At a time when Japanese restaurants proliferated in major American cities Billy succeeded in establishing a successful sake business in New York City. He managed World Sake Imports in Soho until the end of his life.

For several summers we rented a house on Killington. We hiked the slopes, Garvin Hill, the Vermont part of the Appalachian Trail. We socialized with friends.

When the Killington house was no longer available as a summer rental, in 2003 we bought a house in Mendon. Then our stays in Vermont were not limited to summers. When the drive from New York was no longer feasible for Billy and the more than six hour long train ride became intolerable to me, we sold the house in 2013.

Billy loved the New York restaurant scene. We had our favorites, especially Japanese restaurants. He did not always join me in theater or classical concert going. But, if I talked him into coming with me to a fine orchestra performance of a Beethoven symphony at Carnegie Hall, he was game and reveled in the great accoustics.

He could do without opera. There was one opera, however, I insisted he attend with me one New Year’s Eve. The character of sailor Billy Budd bears a resemblance to the country boy Billy Giles. Well, Billy’s reaction was: “I don’t understand why it takes so long to tell that simple story.” After that performance some patrons were invited to a supper party on the Met Opera stage. Billy delighted in poking around in the wings and meeting the singer who had just changed out of his sailor costume and shed his blonde wig.

Leaving the hospital room on the evening of the Sept. 24, I told Billy I had been invited to a party on the roof by one of our neighbors in the building. “I don’t have the patience for a party,” I said, kissing him goodnight. “I’ll see you tomorrow.”

In the raspy remnant of what had once been his elegant speaking voice,Billy whispered the last words I would ever hear him say: “Go to Santoni’s party.”

The morning of Saturday, Sept. 25, I arrived at the hospital to be met by the chief of Billy’s medical team shaking her head. Her patient had fallen into a coma. I spent the next seven hours holding the rigid hand of a once beautiful man, and staring into the gaping grimace of the corpse he had become. Hoping for a response, I whispered and sang to him softly until at 8:30 I felt no more life pulse in his hand. I knew it was all over even before the doctor treated me to the official nod. I watched two nurses zip up William Edward Giles into a white plastic body bag.

Giles was suave and courtly and sophisticated, without ever losing his natural guilelessness. He moved as easily in his native Vermont as he did in New York and Europe. We lived a surprising and magical, adventurous, and cozy life. We could be childishly innocent or fussy and demanding with each other. Our romance of almost 34 years never lost its sheen. I will miss and mourn him every moment of every waking day and night for the rest of my life.

Billy had no children. His mother and father were both dead. His is survived by two cousins, Christina Theriault of Niantic, Connecticut, and Martha Aitken of Williston, Vermont.