By Emma Cotton/VTDigger

Local conservationists say they aren’t surprised by a new report from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service that lists 269 species of birds that need more protection.

The report, called Birds of Conservation Concern, lists species in the United States that aren’t considered federally endangered or threatened, but whose populations are declining.

“It reinforces what we mostly already knew,” said David Mears, executive director of Audubon Vermont and vice president of the National Audubon Society.

Birds that Vermonters commonly see in their backyards could soon edge into the “extinction zone of risk, which we want to stay well clear of,” Mears said.

Several species listed in the report are already considered threatened or endangered in Vermont, but not at the federal level. Vermont conservationists have already succeeded in boosting the populations of previously endangered birds, such as the peregrine falcon, the common loon and the bald eagle.

Among the species listed in the report are the eastern whip-poor-will, wood thrush and veery, which all live in lowland forests; the upland sandpiper, bobolink and eastern meadowlark, all grassland birds; the golden-winged and blue-winged warblers, which live in shrublands; and the chimney swift, which lives in developed areas.

Mears said Vermont has an unexpectedly strong population of golden-winged warblers, whose populations are declining across the Northeast.

“That’s just kind of interesting, that there’s ways in which Vermont’s responsibility is beyond our own borders,” he said. “These are birds that go everywhere, and in some ways, our ability to protect habitat for them is a way of providing a service to the broader globe.”

Data for the report comes from both national literature and observations from birders, and it breaks the country into numbered regions with similar habitat — Vermont is part of both the Lower Great Lakes/St. Lawrence Plain and the Northern Atlantic Forest.

A 2019 study from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology shows that wild bird populations in the United States and Canada have decreased almost 30% in the last 40 years. Climate change could cause the extinction of two-thirds of North American species by the end of the century, according to a 2019 Audubon study.

Another, published in 2017, shows a 14% decline in Vermont’s forest birds over a 25-year period.

Mears and Chris Rimmer, executive director of the Vermont Center for Ecostudies, say conservation efforts in the state focus on both individual species and broader habitat preservation.

Vermont recently removed bald eagles from its endangered species list, for example. The success comes from a combination of targeted efforts to reduce their exposure to harmful pesticides, and big-picture efforts to preserve their habitat — and, by extension, the habitat of other creatures.

In some ways, the collective scope of declining bird populations carries the same symbolism as a single canary in a coal mine, Mears said. Birds need insects, pollinators, grasslands and forests to breed and thrive. Stressed bird populations often show early warning signs of other environmental problems, including climate change.

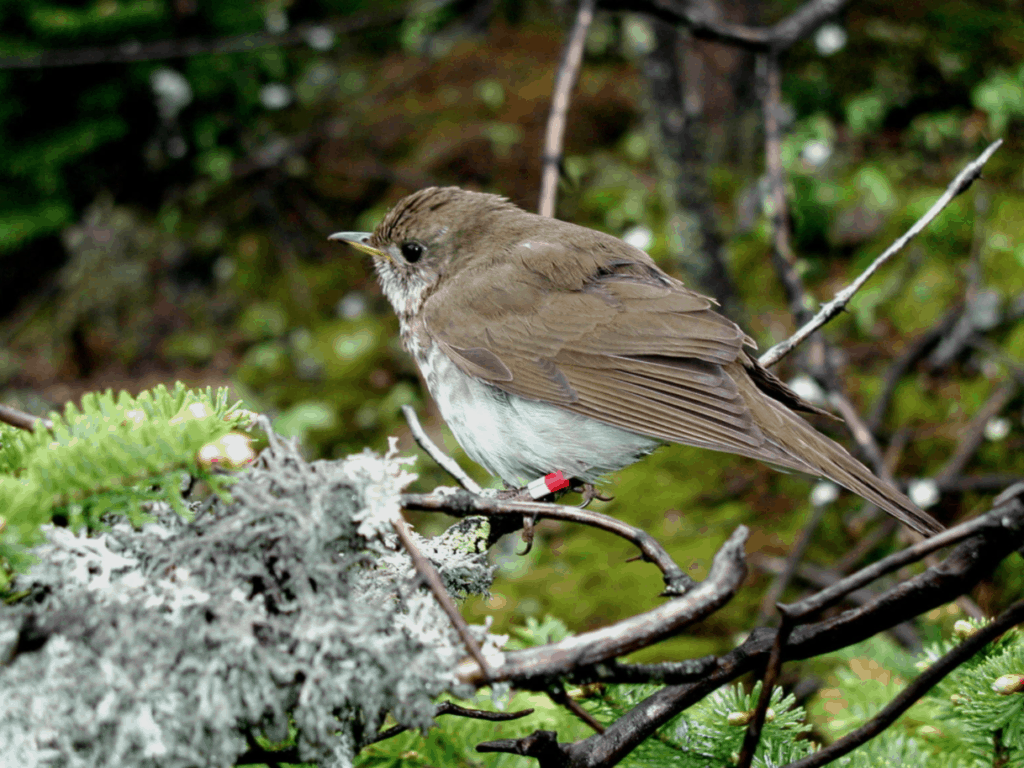

Climate change is likely to stress populations of sensitive species, like the Bicknell’s thrush, which nests only in the high elevations of New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine and some parts of Canada. Rimmer, who has conducted extensive research on the species, said data already shows that hardwood forests are beginning to “march upslope,” slowly migrating to higher elevations.

“Some of these models show that, if we continue on some of the predicted trajectories, Bicknell’s thrush and some other birds are going to potentially disappear from all but the really high mountains, like Mount Washington,” Rimmer said. Mount Washington, at 6,288 feet, is nearly 2,000 feet taller than Mount Mansfield, Vermont’s highest peak at 4,393 feet.

A banded Bicknell’s thrush from one of Rimmer’s studies.

The report notes that its underlying philosophy “is that proactive bird conservation is critical at a time when continued human impacts will be intensified by effects of a changing climate.”

According to the report, conservation efforts that protect species are more cost-effective than efforts to bring species back once they’re officially listed as endangered or threatened. Rimmer says many of the conservation efforts mounted by the Vermont Center for Ecostudies are volunteer-based.

“You could never do it on your own,” he said. “We could never hire enough field technicians to go out and do what all these wonderful, trained, passionate community scientists do.”

Mears hopes the broad interest in birds — which gained traction during the pandemic — might help more regular folks get involved with conservation efforts.

“As people who care about birds see this very tangible impact — the fear of not being able to see indigo buntings, or scarlet tanagers, or losing really common birds like wood thrushes — it really begins to affect the way Vermonters look at and think about these issues,” Mears said. “Realizing that the solutions that benefit wood thrushes also benefit us directly starts to pull in this broader community of public interest.”