By Katie Jickling/VTDigger

Dick Drysdale, a longtime editor, publisher and reporter who spent his life telling stories about — and to — a community he loved, has died. He was 76.

Drysdale manned the helm of the White River Valley Herald (formerly The Herald of Randolph) for more than four decades, documenting the high school graduations, downtown arrests, municipal meetings and local personalities that form the fabric of small-town life.

“Dick was the quintessential journalist,” said Jim Kenyon, a columnist for the Valley News who profiled Drysdale when he retired in 2015. Kenyon described Drysdale’s practice of walking around town and talking to everyone he passed to gather local gossip and news.

“He had the pulse of the community,” Kenyon said. “At the same time, he wasn’t afraid to hold power to account.”

Drysdale, the son of a newspaperman, grew up in the same Randolph home where he died Wednesday, April 28, after a period of declining health, according to his wife, Marjorie Drysdale.

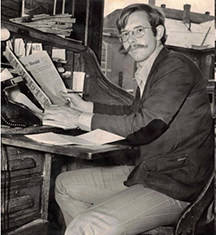

Drysdale, who attended Harvard University, later returned to his hometown to take over the paper from his father, John Drysdale. The younger Drysdale — who often went by “Dickey” or “M.D.” — presided over the paper from behind his roll-top desk, managing about a dozen employees and an aging office littered with newspaper clippings.

He didn’t shy away from conflict, said Sandy Vondrasek, a reporter and editor for The Herald for more than 30 years. Under his leadership, the paper published stories on the turmoil among the leadership at Vermont Tech and the 2012 ouster of the Randolph town manager.

The paper also won several statewide journalism awards for its coverage of Tropical Storm Irene.

But Drysdale also saw value in the more unobtrusive moments that bring families joy and keep the town functioning, Vondrasek said — the rites of passage, moments of beauty and examples of faithful public service.

When Vondrasek joined the staff as a copy editor in 1983, Drysdale assigned her to visit and profile each of The Herald’s correspondents, who covered outlying towns for little recognition and even less money.

“The reporting was important, but it was a community newspaper and a paper that cared about all the towns in the White River Valley,” she said.

Nor did Drysdale take his job too seriously. He prided himself on his convincingly reported April Fool’s Day fake front page. During a particularly treacherous mud season, he invited readers to submit poems about potholes, Vondrasek said.

He prioritized inaugurating young people into the trade — including this reporter — and had a steady stream of interns in the old Randolph offices. They included folks who had no reporting skills to offer but a general sense of curiosity that Drysdale molded into a craft.

Longtime editor, publisher and reporter Dick Drysdale led the Herald of Randolph for more than four decades. Many weigh in to reflect on his legacy.

“He had highfalutin’ college credentials, but as far as I can remember, he never seemed to care about the experience people were bringing,” said Tim Calabro, a photographer who took over for Drysdale as publisher in 2015. “He could see where their talents lay and would make them the best reporter they could be.

“I showed up at the paper, then called The Herald of Randolph, in the fall of 2009. I was a senior in high school, and I had never written a newspaper article. Drysdale agreed on the spot to let me intern and immediately sent me out on an assignment.

“I worked at The Herald that summer and the next. I kept coming back off and on for the next seven years, reporting stories during summer and Christmas breaks, occasionally manning the front desk or editing the copy of other reporters.

“As a Herald intern and reporter, I was on the receiving end of the notorious Drysdale pranks: He would pretend to fall down the stairs behind me as I was descending in front of him and prank-called interns pretending to be an angry reader. In the latter case, I didn’t fall for it. I had received enough forewarning to check the caller ID.

“Once he brought in a marshmallow shooter and sent marshmallows careening off the walls with utter abandon.”

Drysdale was defined by more than just his work, according to friends and colleagues. He and his wife, Marjorie, were married in 1975 and raised two sons.

He embraced the arts, conducting and singing in the local choral group, the Randolph Singers, for 25 years, said Marjorie Drysdale. He helped to resurrect and enliven Chandler Music Hall, joined the Randolph Rotary Club and served on the board of the Vermont Press Association.

In 2015, just before Drysdale retired, the New England Newspaper & Press Association inducted him into the New England Newspaper Hall of Fame. Later that year, he published a compilation of his articles, poetry and essays called “Vermont Moments: A Celebration of Place, People, and Everyday Miracles.”

Even after his retirement, he instilled in young reporters the value of news and of investment in a community, Calabro said.

At one point, he hosted a gathering of high school reporters and interns and asked them why local news was important. Drysdale finished out the meeting with a simple summation, Calabro said: “Bad things happen in a community, and the community deserves to know about it. Good things happen in a community, and the community deserves to celebrate it.”

The advice epitomized the Drysdale approach to news that was both compassionate and unflinching, Calabro said: “It doesn’t have to be complicated. We’re all in this together.”