By Karen D. Lorentz

Editors’ Note: This is part of a series on the factors that enabled Killington to become the Beast of the East. Quotations are from author interviews in the 1980s for the book ‘Killington, A Story of Mountains and Men.’

In 1956, the only way to reach Killington Mountain was via West Hill Road, a steep, narrow dirt road from U.S. Route 4 to the Bates Farmhouse. From there, an old, overgrown logging road led to the base of Killington Peak, some 2 miles away. Despite progress made on the mountain, the state’s building of an access road was delayed by the highway department’s “lack of funds.”

In August 1956, a letter was sent to Killington investors, noting that since plans for operating a ski area for 1956–57 were tabled and the escrow agreement would expire on September 30, 1956, each stockholder and subscriber would be personally visited to discuss stock pledges “since some of you may wish to use the capital.” Many signed a new escrow agreement that would expire in September 1957. Others withdrew their support and were later re-solicited as the 1957 Legislature got underway.

In the meantime, the corporation’s funds for business were limited to those invested by the project’s promoters: the Smiths, Sargents, Joseph Van Vleck, and Walter Morrison. Since April 1956, those assets had quadrupled to $4,800. But after buying the Bates farmhouse and land and equipment in 1956, the cash on hand in January 1957 was $791.66.

Catch-22 and perseverance

It was an uncertain, difficult situation for the fledgling company because, without a road and a lease, it was impossible to sell the stock outright, hence the escrows. “You needed a road and capital to obtain the lease. To raise capital, you needed a road and a lease. And to get a road, there were those who wanted to see capital and a lease. It was a round and round circle of problems,” Sargent had said of the first major hurdle.

It was a “Catch-22” situation that would have deterred a less ambitious group. Undaunted, Smith spent much of the winter of 1956–57 lobbying for an appropriation for the Killington Access Road and looking for investors. With his perseverance, the escrow account grew to $30,000, which would satisfy a stipulation of the proposed Killington Road highway bill before the 1957 Legislature — that the Sherburne Corporation had the money to develop the mountain once the road was in.

Road snag

Vermont was actively looking for ways to bring development into the state in the 1950s, and there were those in state government who saw the development of ski areas as beneficial and desirable. As noted previously, State Forester Perry Merrill was a major proponent of skiing as a natural and efficient way to utilize the mountains and forests while augmenting revenues.

A policy of supporting the creation of ski areas by leasing state land was established during the early 1930s when Mount Mansfield was developed. In the mid-1950s, Governor Joseph B. Johnson supported the policy of the state building roads to access remote mountain areas where private ski developers would lease state forestlands.

Mount Mansfield, Smugglers Notch, Jay Peak, Okemo, and Burke Mountain were all built on leased lands with access roads and base shelters provided by the state. Additionally, the state approved the building of access roads for ski areas located on national forest land (Mount Snow and Sugarbush) and on privately owned land (Stratton).

However, there were those who could not accept the notion of using public funds to build roads for private enterprise. They didn’t see it as the state’s responsibility or as a partnership between the public and private sectors for the betterment of Vermont.

Pres Smith and Joe Sargent recalled members of the highway department telling them: “No way are we going to build you a road to that mountain.”

This was in direct conflict with official state policy, thus setting the stage for potential problems even after the legislature appropriated the funds for the road!

As a newspaper publisher and promoter of industrial development for the Rutland area in the 1950s, Robert Mitchell witnessed much of what occurred within the various state agencies, i.e., the highway department, the highway board, the forests and parks department and board, and the legislature. He noted that personalities and politics had much to do with the delay in getting a road to Killington.

Against this involved political background, the Killington Road Bill was withdrawn in March 1957 in favor of an amendment to a $26-million highway bond bill authorizing $750,000 for building roads leading to ski areas.

In May 1957, appropriations were earmarked for further work on roads for Jay (about $241,000 for two roads), Burke ($126,000), Okemo ($40,000), Killington ($140,000), and Mount Snow ($25,000). The highway bond was signed into law in early June. Another bill appropriating $30,000 for the construction of a base shelter and parking lot at Killington was passed in June 1957.

During the summer, a preliminary survey and engineering of the access to Killington raised the question of a route for Killington Road. There was talk of a road costing $340,000 as the only type to build, and one engineer proposed a higher elevation route.

With the preliminary survey of the road completed in the fall of 1957, the highway department announced that it was too big a job to build a “force account,” i.e., with their own crews, and that the job would be put out to bid. The highway department improved the existing access roads for Jay Peak, Okemo, and Mount Snow, and in the fall began the road for Burke but delayed the Killington project once again.

The Killington Access Road was built in 1958 “by force account and without relocating it,” Mitchell noted.

Convinced that the Killington project received less than a fair shake, he pointed to highway financial reports from this era and noted: “The Vermont Highway Board actually allocated $340,000 for the access road construction, but only $254,512 of it was ever spent. The missing $85,000 was diverted to other construction in the Jay Peak area without the knowledge of the Highway Board by the department’s commissioner and chief engineer, who was personally opposed to the Killington development.”

Good news

A lease, which was substantially the same as that given to Mount Mansfield, was granted to the Sherburne Corporation in November 1957 after Joe Sargent made a presentation to the Forest and Parks Department. It included the project’s history, accomplishments, plans, description of who was involved in the development, and several exhibits, including a balance sheet as of October 31, 1957. Assets totaled $118,000, of which $8,000 was from a loan and $110,000 from stock sales. The cost of the work road and bridge, two Pomalifts, two bulldozers, two jeeps, a truck, chain saws, a house, and much small equipment had exceeded $68,000.

In case that was not impressive enough, Sargent estimated that “of the 20 areas we expect to see in operation next year in the State of Vermont, we will rank ninth in lift line length, sixth in drop, and second in altitude.

Next week, we’ll look at the progress made on the mountain and an unusual stock story, both of which indicate the caliber and dedication of the developers of the ski area.

Comments and insights are welcome: email [email protected] to share thoughts about skiing in the 1950s.

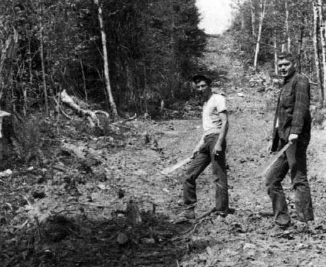

Ralph Moral and Pres Smith cut brush away in preparation for the first lift line.

Pres Smith at the top of the first poma lift line, December 1957.