With home viewing becoming the preferred way to watch movies, it’s a rare delight to encounter a film that demands to be seen in a theater. Brady Corbet’s “The Brutalist” is one such film. This 215-minute epic, shot in stunning VistaVision and presented in 70mm, is a cinematic experience that makes the journey to the theater worthwhile and essential.

Corbet, a one-time film actor, may be best known, to me anyway, as the creepy, malevolent, tennis outfit-wearing companion to Michael Pitt in Michael Heneke’s English-language remake of “Funny Games.” Corbet established himself as a potential filmmaking force to be reckoned with in his first two films of uncompromising vision, “The Childhood of a Leader” and “Vox Lux.” While each has its merits and flaws, one thing was clear: these were the brainchildren of a director with a mission and talent. However, nothing Corbet previously put forth in those two efforts could prepare me for what he unleashes in his latest offering, “The Brutalist.”

Adrien Brody delivers a towering performance as László Tóth, a Hungarian-Jewish architect and Holocaust survivor navigating post-war America. Haunted by the weight of untold horrors, Tóth arrives in Philadelphia in 1947, physically and emotionally scarred yet determined to start anew. Brody’s performance reminds audiences that he is a high-caliber actor, and it’s difficult to imagine anyone else playing this role. He’s brilliant in the film.

A story of struggle and genius

The film spans 1947 to 1960, with an epilogue in 1980, tracing Tóth’s journey from refugee to reluctant participant in the American Dream. Upon his arrival, he finds refuge with his cousin, whose assimilation into American culture—complete with a Catholic wife and an Anglo-Saxon name—only highlights Tóth’s alienation.

Corbet masterfully explores how America’s post-war optimism coexisted with xenophobia and anti-Semitism, both of which Tóth encounters as he tries to rebuild his life. There are no flashback scenes of the Holocaust, but its shadow looms over every frame, embodied in Brody’s performance, where every gesture and pause conveys a history of pain.

Despite his struggles, Tóth’s genius as an architect shines through. When commissioned to remodel a home library, his transformation of the space elicited an audible gasp from the audience at my screening—a rare moment of collective awe and another reminder of what the communal experience of seeing a film in a theater packed with 550 other filmgoers can bring.

Yet, Tóth’s journey is far from smooth. His potential rise is thwarted when the industrialist who owns the library, Harrison Lee Van Buren, objects to the surprise renovation. Played with smarmy charm by Guy Pearce in a career-best performance, Van Buren offers Tóth a second chance—a monumental project to design a community center. The job comes with enticements: Van Buren promises to help Tóth reunite with his wife and niece, still trapped in Europe.

A Faustian bargain

Van Buren is both liberator and oppressor, representing the intoxicating allure and insidious dangers of power. His dynamic with Tóth becomes the film’s emotional and ethical core. Pearce imbues Van Buren with an unsettling charisma, his interactions with Tóth oscillating between mentorship and manipulation.

Van Buren is a monster, at times an affable monster, but a monster all the same. His demons may be different from Tóth’s, but they will threaten Tóth in ways more damaging than Tóth’s already destructive behavior ever could.

Van Buren’s son Harry, is played by Joe Alwyn, whose inability to match his father’s dominance adds another layer to the film’s exploration of power and identity. The younger Van Buren lives in his father’s shadow, and he can dress, present himself, and even mimic the same pretentious affectation of his more successful father, but he’ll never measure up. And by the end of the film, you’ll understand that measuring up to this man is not something you’d want to do in the first place.

Corbet captures these tensions with striking visual precision, aided by Lol Crawley’s luminous cinematography and Dávid Jancsó’s innovative editing. VistaVision, a process rarely employed since the 1960s, lends the film a period authenticity and a painterly quality that digital cameras struggle to replicate.

An unforgettable cinematic experience

Following the intermission, we meet Erzsébet (Felicity Jones) and Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy), whose arrival in America brings relief and heartbreak. Erzsébet, once a celebrated journalist, now bears the physical and emotional scars of years spent under Nazi and Soviet rule. Her reunion with Tóth is fraught with tension, as both struggle to reconcile the people they once were with who they have become.

Jones delivers one of the film’s many standout performances, capturing Erzsébet’s resilience and quiet strength. Her scenes with Brody are among the film’s most poignant, as they navigate the complexities of love and survival of two souls trying to reconcile what once was with what is after so many lost years under the worst of circumstances.

The visual splendor is unparalleled for those fortunate enough to see “The Brutalist” in 70mm. The Somerville Theater in Massachusetts, where I saw the film, offers a perfect showcase for the format, ensuring that every detail of Corbet’s vision is preserved.

A testament to cinema

“The Brutalist” is more than a film; it reaffirms cinema’s potential to inspire and challenge. Whether experienced in its full 70mm glory or on a more conventional screen, it’s a journey worth taking.

As Corbet’s film reminds us, when it comes to art, it’s not the journey but the destination that matters. And this destination is unforgettable. I have several more 2024 films on my must-watch list, but nothing I will see will topple this film from the top of my best-of-the-year list.

James Kent is the assistant to the publisher at The Mountain Times and the co-host of the “Stuff We’ve Seen” podcast at stuffweveseen.com.

“The Brutalist” brilliantly captures the immigrant struggle in America during the 1950’s.

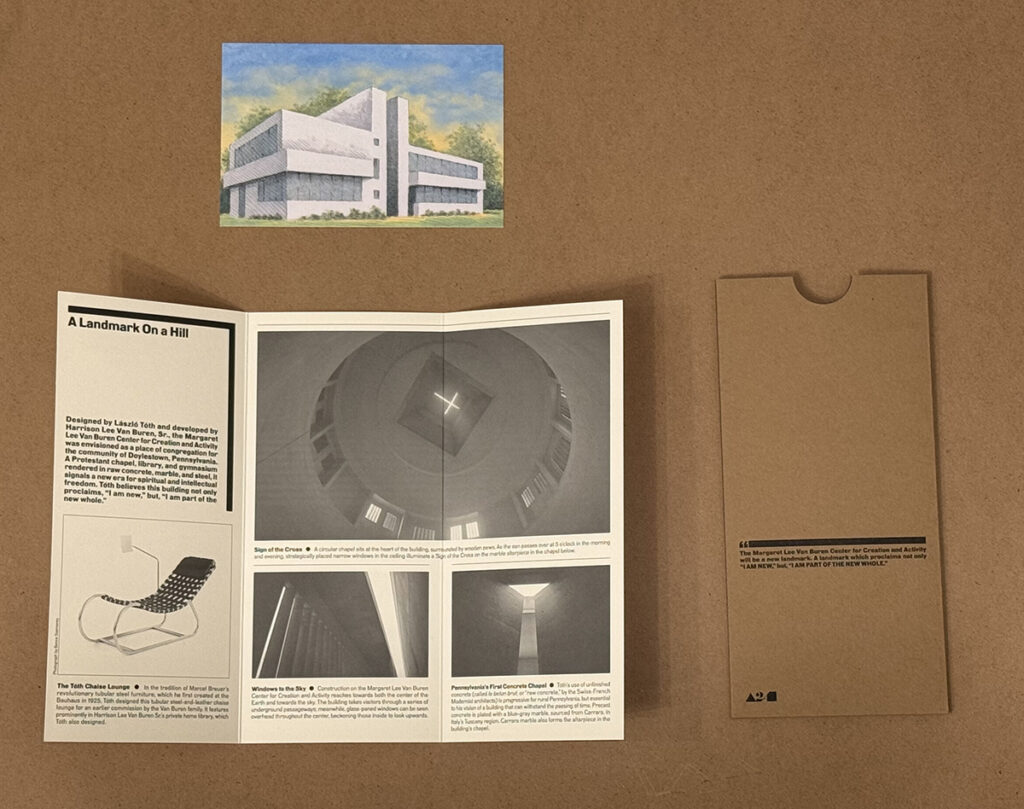

Attendees at special 70mm showings of “The Brutalist” received mock gallery brochures and postcards of architect László Tóth’s work.